Editor’s Note: Thomas O’Dwyer wrote almost fifty essays for 3QD which you can see here.

by Michal Yudelman-O’Dwyer

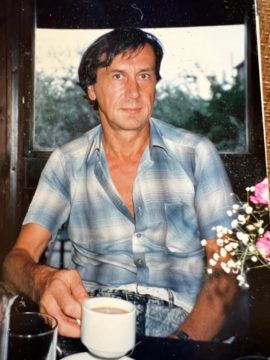

Thomas O’Dwyer, my husband, died on Wednesday. He wouldn’t approve of this beginning. In his articles he always came up with something original or intriguing to draw the reader in.

Thomas O’Dwyer, my husband, died on Wednesday. He wouldn’t approve of this beginning. In his articles he always came up with something original or intriguing to draw the reader in.

Thomas was so many things, but first of all a writer. He never stopped seeking facts and information up to his last night in hospital. He had a quick Irish temper and no patience for slow understanding or explaining things twice, which sometimes made things difficult, especially if you were always asking him how to do this or that on the computer, or to edit something you wrote, as I did.

He was also generous and caring and had a weakness for street cats, which he fed every day in our building’s back yard until the last trip to the hospital. All our house cats over the generations were street cats who’d wandered in, or which he’d found as kittens.

As a fearless war correspondent, he had hair raising tales, sometimes sounding, how shall I put it, somewhat enhanced. But there was nothing enhanced about his reporting. His pursuit of the truth was relentless and everything he wrote depended on the background of his vast knowledge and understanding.

His daughter Fiona said he’d told her as a child, when he was Reuters’ bureau chief in Nicosia, that as a journalist it was his responsibility to know the history of “every country in the world.”

Born in Clonmel, County Tipperary, Thomas grew up in the village Athgarvan, County Kildare, without running water or electricity. His father was in the IRA. From a young age he was determined to travel and see the world. When he became a fighter pilot in the Royal Air Force, where he flew a Vulcan bomber, his mother told the neighbors he was working for Irish Airlines (if anyone asked about his RAF uniform).

Born in Clonmel, County Tipperary, Thomas grew up in the village Athgarvan, County Kildare, without running water or electricity. His father was in the IRA. From a young age he was determined to travel and see the world. When he became a fighter pilot in the Royal Air Force, where he flew a Vulcan bomber, his mother told the neighbors he was working for Irish Airlines (if anyone asked about his RAF uniform).

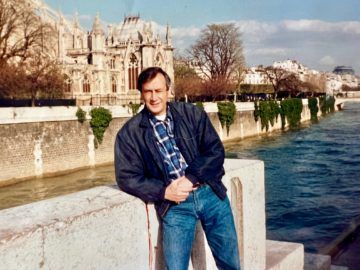

After 12 years in the RAF Thomas decided he wanted to be a writer. He moved back to loved Cyprus, which he’d loved when he served there in the RAF. “It’s like Ireland, but with sun,” he used to say.

He started writing children’s stories, then became editor of the Cyprus Mail. Soon after that he was hired by Reuters to set up the agency’s first permanent bureau in Nicosia, which was in charge of its Middle East coverage.

He often told the story about sitting in a pub in Nicosia with other journalists one night when they heard an explosion and shell fire. Everyone jumped up looking for the nearest pay phone when someone said, “Oh, let the agencies cover it.” They all sat down again, Thomas included, and ordered another round. “Then it hit me: I’m the agencies!” Thomas recalled. He scrambled to cover the story, which the newspapers later took from Reuters.

He often told the story about sitting in a pub in Nicosia with other journalists one night when they heard an explosion and shell fire. Everyone jumped up looking for the nearest pay phone when someone said, “Oh, let the agencies cover it.” They all sat down again, Thomas included, and ordered another round. “Then it hit me: I’m the agencies!” Thomas recalled. He scrambled to cover the story, which the newspapers later took from Reuters.

In November 1983 Thomas published an exclusive interview with President Raul Denktash at the Presidential Palace in North Nicosia, after the proclamation of the Turkish-Cypriot state in the northern one third of the island. He also covered the war in Lebanon in the 80s and the Iran-Iraq war, and did a two-year stint for Reuters in Bahrain and Dubai, before moving to Israel.

In Israel he started working at the Jerusalem Post, where he was quickly appointed Foreign editor and his column – Column One – was published three times a week, in addition to his frequent editorials.

I’d been working at the Post for more than a decade when Thomas was appointed bureau chief of what he called “the city state of Tel Aviv,” in addition to his other positions.

I’d been working at the Post for more than a decade when Thomas was appointed bureau chief of what he called “the city state of Tel Aviv,” in addition to his other positions.

On one of our first dates, when we’d decided just to meet at my place rather than go out, I wondered aloud, “what will we do?” Secretly I was afraid my company alone wouldn’t be scintillating enough and was relieved when he casually suggested poetry reading. I prepared my trusty though crumbling Norton Anthology of English Poetry from the ‘70s. When he showed up at the door, all he had was a bottle of wine.

“Didn’t you bring a book?” I asked him.

“Who needs a book for poetry reading?” he said.

It turned out he wasn’t kidding. He could quote most poems I wanted to read by heart. I think that was the moment I knew he was the one. Mind you, what I really fell for was his sense of humour, which had me in stitches a lot of the time. After a while I tried to jot down some of the things he said before I’d forget them.

“I don’t want to live with someone who’s going to follow me around with a yellow notebook writing down everything I say,” he snapped irritably.

Another time he warned me that “funny people” are very hard to live with, as they tend to be morose characters and could even become tedious, once their jokes started repeating themselves. Naturally, I totally ignored his warning.

Thomas was passionate about justice and equality causes and couldn’t bear prejudice and bigotry. Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination in 1995 shocked him to the core and he noted how rare it was in history that a terrorist changes the course of events. We both knew then that the peace process had been dealt a fatal blow, despite the prevailing political analyses at that time.

Thomas was passionate about justice and equality causes and couldn’t bear prejudice and bigotry. Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination in 1995 shocked him to the core and he noted how rare it was in history that a terrorist changes the course of events. We both knew then that the peace process had been dealt a fatal blow, despite the prevailing political analyses at that time.

In 2000, after the Jerusalem Post had veered sharply to the right, Thomas started editing and writing a column – Nothing Personal – in Haaretz’s English edition, a joint venture with the International Herald Tribune and currently with the New York Times. He has written and edited several books, the latest of which, Conversation, he co-wrote with his close friend, former journalist and businessman Bill Hutman.

His life could have filled a number of lifetimes, but wasn’t enough for my lifetime. It feels wrong to use the word “end” in connection with Thomas, because he will never end. Yes, life will go on without him, but not my life.

As a lover of science fiction and futuristic literature, films and series, I think Thomas would appreciate how I devised to keep him alive a little longer. In the first few days I didn’t pass on to a very close friend of ours, who was abroad, that he had died. I waited until her return. I didn’t want to spoil her holiday, of course. But more importantly, a little like Shrödinger’s cat, Thomas continued to live as long as she thought he was alive.

It’s customary for a grieving spouse to thank the deceased for their amazing life together. I feel no gratitude, but rather anger. My last words to him would be – how, how could you leave me? We were supposed to stay together. Or in the words of W.H. Auden in “Funeral Blues” – Thomas would balk at the overused quote – “I thought that love would last forever, I was wrong.”

He said more than once that he didn’t come to change me, but to change my life. Thomas died on Wednesday and changed everything.

***

Thomas is mourned by his wife Michal, daughter Fiona, grandchildren David, Emma and Chloe and sister Fidelma.

***

Michal Yudelman-O’Dwyer is a journalist, writer and translator. She was born on Kibbutz Hatzerim in the Negev, Israel, to where her parents immigrated from South Africa as pioneers in 1948. After high school she served in the Israel Defense Forces with an Intelligence Corps unit based in the Sinai. She studied English Literature and Philosophy at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, then in the U.S. where she received an M.A. from the University of Chicago. While studying for her Ph.D in Communication at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, she began her career in journalism, editing and writing for the Utah Chronicle.

Michal Yudelman-O’Dwyer is a journalist, writer and translator. She was born on Kibbutz Hatzerim in the Negev, Israel, to where her parents immigrated from South Africa as pioneers in 1948. After high school she served in the Israel Defense Forces with an Intelligence Corps unit based in the Sinai. She studied English Literature and Philosophy at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, then in the U.S. where she received an M.A. from the University of Chicago. While studying for her Ph.D in Communication at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, she began her career in journalism, editing and writing for the Utah Chronicle.

On returning to Israel she worked with The Jerusalem Post, covering several news beats, including crime, business, politics and diplomatic affairs. She wrote a weekly political column, The Week That Was, a consumer affairs column, and magazine features. In 2002 she joined Haaretz’s English edition (International Herald Tribune) as a Hebrew-English translator and editor on the night desk. She free-lanced for the BBC and RTE. She was married to the Irish journalist Thomas O’Dwyer, who died on Wednesday last week. She lives in the couple’s apartment in central Tel Aviv.