by Derek Neal

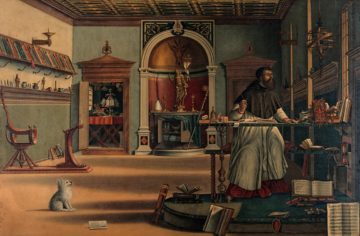

According to my father, David Mamet once said that his scripts are about “men in confined space.” I have been unable to verify this quote, but if you look on the internet, there’s an awful lot of writing about Mamet and “confined space.” In particular, I suspect the origin of this apocryphal statement may be a review of American Buffalo by Roger Ebert, in which he mentions that Mamet’s play succeeds where the film fails because, on stage, the characters are “trapped in space and time,” while on the screen they seem “less confined.” It goes without saying that a film allows for greater movement of its characters than a play, but a movie can trap its characters if it chooses to, and this choice can be all the more effective because it’s a conscious one, not something imposed by circumstances. One film that makes this choice is Living, which I saw this past weekend.

According to my father, David Mamet once said that his scripts are about “men in confined space.” I have been unable to verify this quote, but if you look on the internet, there’s an awful lot of writing about Mamet and “confined space.” In particular, I suspect the origin of this apocryphal statement may be a review of American Buffalo by Roger Ebert, in which he mentions that Mamet’s play succeeds where the film fails because, on stage, the characters are “trapped in space and time,” while on the screen they seem “less confined.” It goes without saying that a film allows for greater movement of its characters than a play, but a movie can trap its characters if it chooses to, and this choice can be all the more effective because it’s a conscious one, not something imposed by circumstances. One film that makes this choice is Living, which I saw this past weekend.

The first scene of the film sees Mr. Wakeling, young and fresh faced, join his new colleagues on the platform of the local train station. They’re heading into London for the day’s work, and they, along with most everyone else on the platform, are dressed in suit, tie, and jacket. It’s 1953. Because it’s Mr. Wakeling’s first day, he’s unsure about what the appropriate etiquette is. He’s not at work yet, and he hasn’t met two of his new colleagues, although he does recognize a third from the interview. Should he go over and introduce himself? Should he avoid them, pretend he hasn’t noticed them standing there? He makes eye contact with the one he recognizes from the interview, who nods almost imperceptibly, granting him permission and entry into their group. Read more »

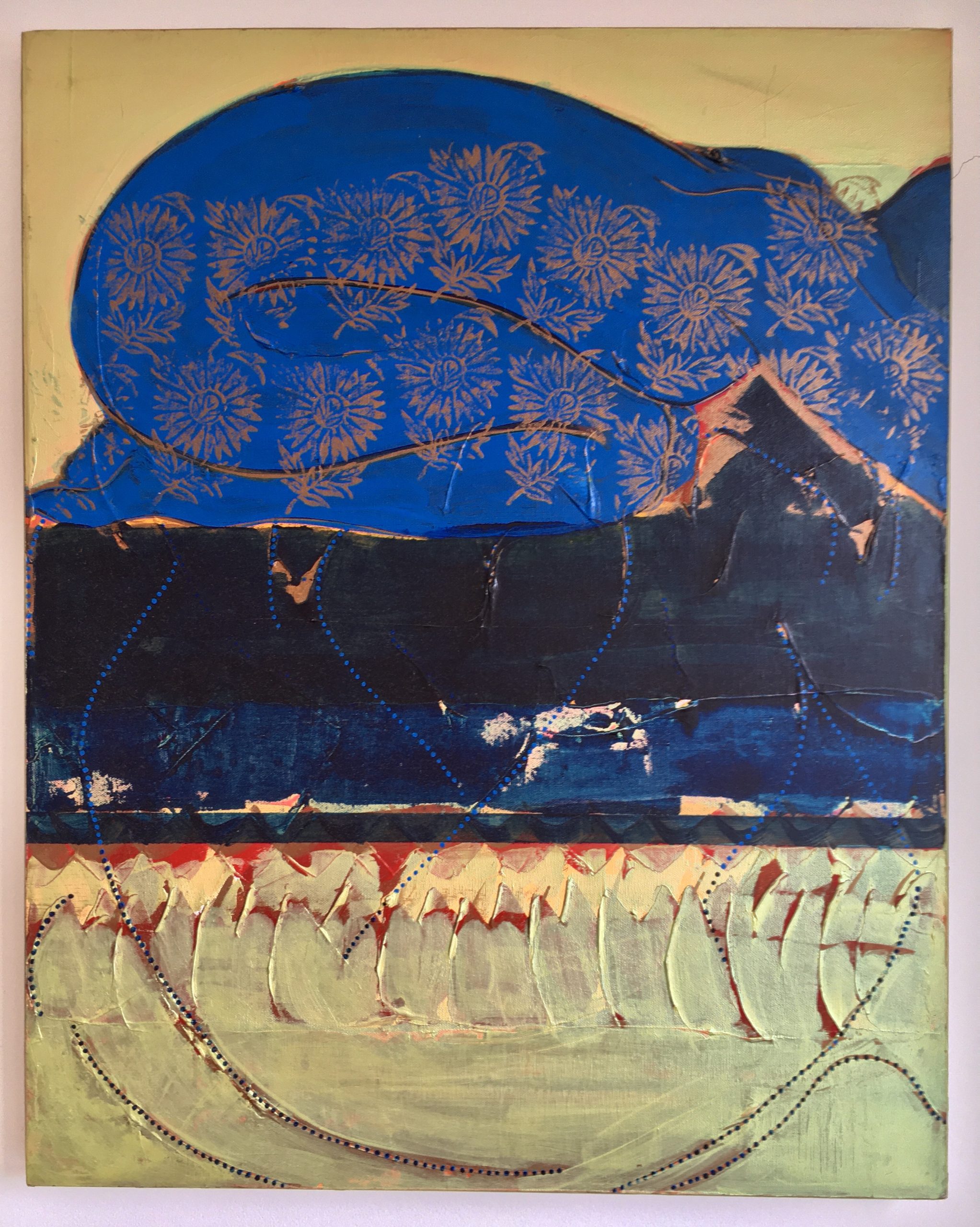

Kevin Beasley. Reunion.

Kevin Beasley. Reunion.

My favorite bookstore closed this month. Well, my favorite bookstore in Zurich, where I live. Also it hasn’t actually closed, it’s only changing hands. But

My favorite bookstore closed this month. Well, my favorite bookstore in Zurich, where I live. Also it hasn’t actually closed, it’s only changing hands. But

The season finale of

The season finale of  Two weeks ago, outside a coffee shop near Los Angeles, I discovered a beautiful creature, a moth. It was lying still on the pavement and I was afraid someone might trample on it, so I gently picked it up and carried it to a clump of garden plants on the side. Before that I showed it to my 2-year-old daughter who let it walk slowly over her arm. The moth was brown and huge, almost about the size of my hand. It had the feathery antennae typical of a moth and two black eyes on the ends of its wings. It moved slowly and gradually disappeared into the protective shadow of the plants when I put it down.

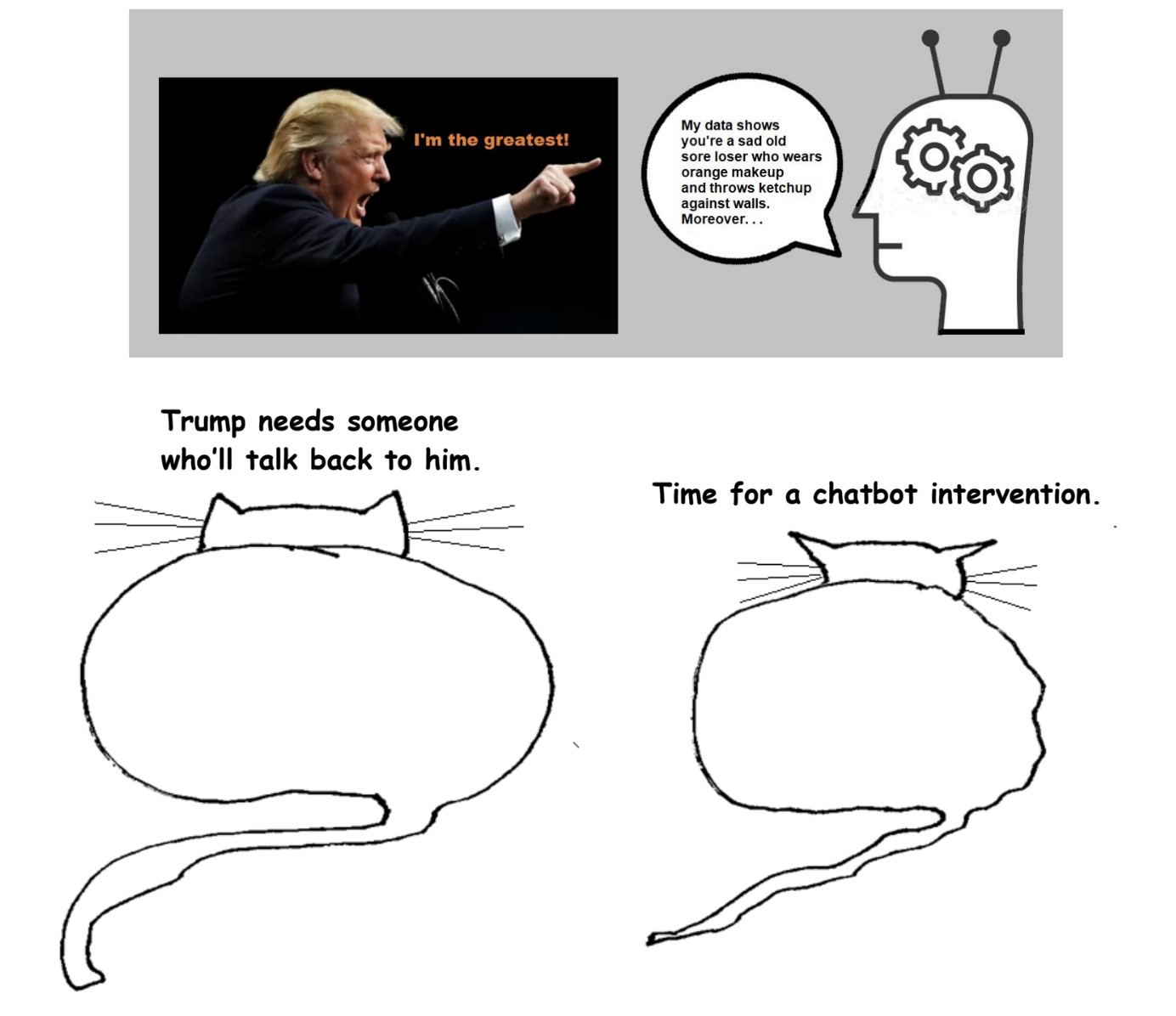

Two weeks ago, outside a coffee shop near Los Angeles, I discovered a beautiful creature, a moth. It was lying still on the pavement and I was afraid someone might trample on it, so I gently picked it up and carried it to a clump of garden plants on the side. Before that I showed it to my 2-year-old daughter who let it walk slowly over her arm. The moth was brown and huge, almost about the size of my hand. It had the feathery antennae typical of a moth and two black eyes on the ends of its wings. It moved slowly and gradually disappeared into the protective shadow of the plants when I put it down. Philosopher Harry Frankfurt is best known for his article-turned-manuscript On Bullshit, in which he distinguishes between lying and bullshitting. Most of us are raised to condemn liars more than bullshit artists, but Frankfurt makes the claim that we’ve all got it backwards. His argument is philosophical, rather than scientific, which means observable evidence is hard to come by, but recent political events have filled the gap.

Philosopher Harry Frankfurt is best known for his article-turned-manuscript On Bullshit, in which he distinguishes between lying and bullshitting. Most of us are raised to condemn liars more than bullshit artists, but Frankfurt makes the claim that we’ve all got it backwards. His argument is philosophical, rather than scientific, which means observable evidence is hard to come by, but recent political events have filled the gap.

Sughra Raza. Untitled. Cambridge, 1999-2000.

Sughra Raza. Untitled. Cambridge, 1999-2000. Having

Having

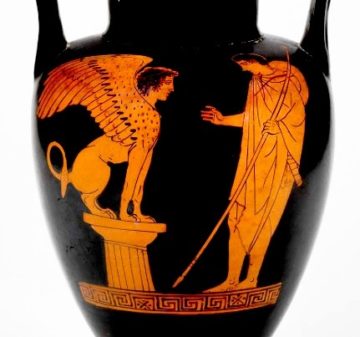

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.