by Rafaël Newman

I am not outside the language that structures me, but neither am I determined by the language that makes this ‘I’ possible. —Judith Butler

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club criticized as “transmisogynistic”; the backlash against the non-Jewish Helen Mirren playing Golda Meir; or the foofaraw over Bradley Cooper’s prosthetic proboscis in Maestro. These attempts to increase minority visibility, no doubt well-meaning and long overdue, were taken ad absurdum with the Met’s 2019 choice of a Chinese soprano for the title role in Madama Butterfly, in a cringingly tone-deaf bid to make up for the tradition of Westerners singing the eponymous Japanese heroine.

The force of recent attempts to increase minority visibility in the performing arts, principally in the US, by matching the identity of the performer with that of the role—in effect a form of affirmative action—has been diminished by a series of tabloid “scandals”: the casting of Jared Leto as a trans woman in Dallas Buyers Club criticized as “transmisogynistic”; the backlash against the non-Jewish Helen Mirren playing Golda Meir; or the foofaraw over Bradley Cooper’s prosthetic proboscis in Maestro. These attempts to increase minority visibility, no doubt well-meaning and long overdue, were taken ad absurdum with the Met’s 2019 choice of a Chinese soprano for the title role in Madama Butterfly, in a cringingly tone-deaf bid to make up for the tradition of Westerners singing the eponymous Japanese heroine.

A salutary, if ironic corrective to this essentialism is offered by casting members of “minority” groups—the term is (mis)used advisedly to include women—explicitly against type: Denzel Washington as Macbeth, for instance, or Glenda Jackson as King Lear. Ironic, because such creative, intentional miscasting replicates the very misprision criticized on the part of the hegemon, which allegedly seeks to reserve privilege to its own replicants at the cost of the subaltern. The maneuver is salutary, however, both morally and aesthetically, because it proactively rights a wrong of exclusion, while opening up new avenues for the interpretation of established works of art. Once such a creatively “wrong” choice is made, in other words, and a given Western canonical work is no longer the account of a particular (most often white, cis-male, hetero) subject, it becomes—although the term is regularly subject to post-structuralist suspicion—universal. And finally, by playing the hegemon, the subaltern reveals the political and linguistic constructedness of that hegemon’s subject position.

These were among the thoughts that preoccupied me as I prepared for a house concert last month with my friends Annina Haug and Edward Rushton. Read more »

1.

1. Jeannette Ehlers. Black Bullets, 2012.

Jeannette Ehlers. Black Bullets, 2012. How plastic – really plastic – gelatin presents as a food. Not only in the “easily molded” sense of a pliable art material but also its transparency. Walnuts and celery, the “nuts and bolts” of gelatin desserts, defy gravity, floating amidst the cheerful jewel-like plastic-looking splendor of the 1950’s, when gelatin was the king of desserts. Gelatin’s mid-century elegance belies its orgiastic sweetness, especially the lime flavor, which is downright otherworldly. If you stir it up hot, half diluted, gelatin lives up to its derelict reputation with regard to the sickbed and sugar, being thick and warm, twice as intoxicatingly sweet, and surely terrible for an invalid’s teeth, if not metabolism. In my novel, Dog on Fire, I hypothesize that lime-flavored gelatin is the perfect murder weapon.

How plastic – really plastic – gelatin presents as a food. Not only in the “easily molded” sense of a pliable art material but also its transparency. Walnuts and celery, the “nuts and bolts” of gelatin desserts, defy gravity, floating amidst the cheerful jewel-like plastic-looking splendor of the 1950’s, when gelatin was the king of desserts. Gelatin’s mid-century elegance belies its orgiastic sweetness, especially the lime flavor, which is downright otherworldly. If you stir it up hot, half diluted, gelatin lives up to its derelict reputation with regard to the sickbed and sugar, being thick and warm, twice as intoxicatingly sweet, and surely terrible for an invalid’s teeth, if not metabolism. In my novel, Dog on Fire, I hypothesize that lime-flavored gelatin is the perfect murder weapon.

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

I am sitting on the couch of our discontent. The Robot Overlords™ are circling. Shall we fight them, as would a sassy little girl and her aging, unshaven action star caretaker in the Hollywood rendition of our feel good dystopian future? Shall we clamp our hands over our ears, shut our eyes, and yell “Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah!”? Shall we bow down and let the late stage digital revolution wash over us, quietly and obediently resigning ourselves to all that comes next, whether or not includes us?

I am sitting on the couch of our discontent. The Robot Overlords™ are circling. Shall we fight them, as would a sassy little girl and her aging, unshaven action star caretaker in the Hollywood rendition of our feel good dystopian future? Shall we clamp our hands over our ears, shut our eyes, and yell “Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah! Nah!”? Shall we bow down and let the late stage digital revolution wash over us, quietly and obediently resigning ourselves to all that comes next, whether or not includes us? I first became aware of Miriam Lipschutz Yevick through my interest in human perception and thought. I believed that her 1975 paper,

I first became aware of Miriam Lipschutz Yevick through my interest in human perception and thought. I believed that her 1975 paper,

At dusk, the shaft of light striking Rumi’s tomb is emollient as pale jade. It has been a long, hot day in Konya, I’ve been writing in a café-terrace overlooking the famed white and turquoise structure of the tomb-museum complex. I sip my tea slowly, facing the spare, elegant geometry of the building that appears as a simple, intimate inscription on the vast blue. For once I am studying Rumi’s verses in Persian, not repeating English translations or paraphrasing in Urdu. “Bash cho Shatranj rawan, khamush o khud jumla zaban,” “Walk like a chess piece, silently, become eloquence itself!” I’m reciting to myself in the din, in awe of the kind of magnetism that would pull one as a chess piece. Only the heart understands this logic, not any heart, but the one that has been broken open, the one that is led to the mystery in cogent silence.

At dusk, the shaft of light striking Rumi’s tomb is emollient as pale jade. It has been a long, hot day in Konya, I’ve been writing in a café-terrace overlooking the famed white and turquoise structure of the tomb-museum complex. I sip my tea slowly, facing the spare, elegant geometry of the building that appears as a simple, intimate inscription on the vast blue. For once I am studying Rumi’s verses in Persian, not repeating English translations or paraphrasing in Urdu. “Bash cho Shatranj rawan, khamush o khud jumla zaban,” “Walk like a chess piece, silently, become eloquence itself!” I’m reciting to myself in the din, in awe of the kind of magnetism that would pull one as a chess piece. Only the heart understands this logic, not any heart, but the one that has been broken open, the one that is led to the mystery in cogent silence.

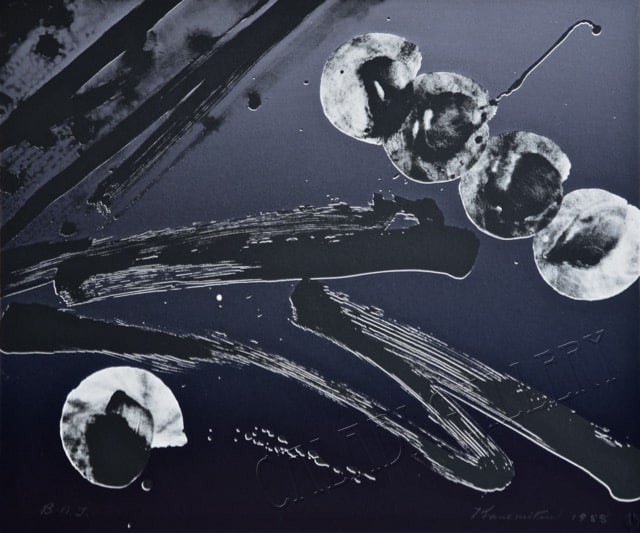

Matsumi Kanemitsu. For The Dream, 1988.

Matsumi Kanemitsu. For The Dream, 1988. “This is the story of a man. Not rich and powerful, not a big man like your father, Sweetheart. Just a funny little man. I didn’t know him long, only three nights. But there was something about him, something magical.” If “Rumpelstiltskin” started with this framing, we would have a different picture of the story’s meaning, a truer picture, for this framing suggests what is hidden below the surface.

“This is the story of a man. Not rich and powerful, not a big man like your father, Sweetheart. Just a funny little man. I didn’t know him long, only three nights. But there was something about him, something magical.” If “Rumpelstiltskin” started with this framing, we would have a different picture of the story’s meaning, a truer picture, for this framing suggests what is hidden below the surface.