by Martin Butler

Going with the evidence is one of the defining principles of the modern mind. Science leads the way on this, but the principle has been applied more generally. Thus, enlightened public policy should be based on research and statistics rather than emotion, prejudice or blind tradition. After all, it’s only rational to base our decisions on the observable evidence, whether in our individual lives or more generally. And yet I would argue that evidence, ironically, indicates that in some respects at least we are far too wedded to this principle.

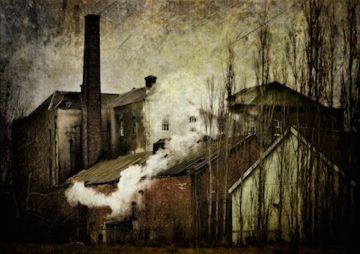

How is it that the dawning of the age of reason, which saw science and technology become preeminent in western culture, coincided with the industrial revolution, which is turning out to be disastrous for the natural world and, quite possibly, humanity too? Our rationalism seems to have created something which is, in retrospect at least, deeply irrational.

When the industrial revolution was moving through the gears from the end of the 18th century and throughout the 19thcentury there was little clear evidence of the environmental disasters awaiting us. Of course many voices revolted against the tide but these voices were almost exclusively based on emotion and romanticism rather than hard scientific evidence. Why shouldn’t we do something if there is no evidence of harm? And offending our sensibilities does not constitute harm. The colossal productive power unleashed by the industrial revolution promised many benefits, and the dark satanic mills were just the price we had to pay for wealth and progress. No matter how ugly the change might appear at first, breaking with the past was surely just the inevitable tide of history. Looking back, however, it seems the romantics, the traditionalists and even the Luddites had a point.

So, where and why did it all go wrong? Science only finds something if it is looking for it, and it never just looks for evidence. It frames research questions in a particular way and uses particular methods to investigate. All this rests on assumptions which are not themselves questioned.

Certainly with regard to the industrial revolution, it took some time before the right questions were being asked and the methods sufficiently refined to come up with reliable answers about environmental damage. The factory acts of the 19th century were a response to the obvious harm caused to workers by the appalling working conditions it produced, but environmental harm was something else entirely. Exploiting human beings is an obvious moral wrong, exploiting nature is just evidence of human ingenuity. By the time alarm bells were beginning to ring, the damaging industrial processes had become embedded in western societies and, increasingly, elsewhere. The genie was out of the bottle. There would be no turning back or even moderation of the damage, at least until very recently.

Some entrenched assumptions worked against caution, one being that the earth and the natural world is almost infinitely vast and resilient. The 19th century economist David Ricardo speaks of the ‘original and indestructible powers of the soil’[1]. Another assumption, which can be traced back to the Old Testament, is that the natural world is a resource at the disposal of humankind. We might want to argue with this interpretation (and the translation) but certainly many Christians at the time did interpret the passages about ‘dominion’ and ‘subduing’ the earth (Genesis 1: 26-28) to mean exactly that, and the enlightenment did nothing to improve things. With its focus on human dignity and reason, there was little recognition of our dependence on the natural world. Although the value and importance of nature was a central theme of Romanticism, which flourished during the first half of the 19th century, ultimately it was no match for the industrial revolution. Progress was about asserting the supremacy of human reason, and romanticism seemed backward-looking in comparison. Matter (and this came to include the natural world) was increasingly seen as just dead stuff governed by mechanical laws, and the idea that a mountain or an animal or a forest could be sacred, while it has a certain poetic quaintness, ultimately finds no place within the western mind. This approach leads to an instrumentalism still dominant in our attitudes towards the environment. What is known as shallow ecology argues that we need to protect the environment simply because it is in our interests. Deep ecology on the other hand, which is very much a minority belief, takes the view that the natural world has an intrinsic value in itself, quite apart from the well-being of humankind.

Thus the problem: if we wait for hard evidence before restraining our activities, it may already be too late. Evidence of harm is clearly dependent on our assumptions about what has and has not the capacity to suffer harm, and this in turn depends on our beliefs and values. If nature is regarded as nothing more than interlocking physical systems, any deep notion of harm gets lost: can we really harm mere physical stuff? Certainly we can disrupt these systems, whether biological, ecological or meteorological, but according to the shallow ecologists at least, harm only occurs when the disruption impacts human life, and tracking down evidence of this can be long winded and complicated. It’s also worth noting that much of the force of shallow ecology comes from effects felt by those who do not as yet exist (i.e. future generations), and therefore lacks the power to move us in the here and now, unlike say a present day famine observed at the flick of a TV remote control. ‘Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof’, as the biblical injunction goes.

It’s often unclear what evidence of potential future harm would even look like. The economic crash of 2007/2008 for example caused much harm, but it’s not as if economists failed to do appropriate research which could have predicted it. Nor is it clear what form such research would have taken. As with environmental harms, it was more a matter of unquestioned and unjustified assumptions (as for example the idea of ‘market equilibrium’) and a blithe over-confidence in particular models about how the economy works.

So should we abandon the evidence-based approach to society? Not quite, but we do need to recognise that it is profoundly inadequate as a sole guide to our actions. With regard to the environment, it’s highly unlikely that there will be a mass conversion to deep ecology or pantheism, so perhaps the next best thing is the adoption of what is known as the precautionary principle. This states that we cannot always afford to wait for evidence, but rather must take an attitude of care and precaution when embarking on any project that might potentially cause harm. If we are going to stick with shallow ecology, the precautionary principle seems essential. Though there are many questions about this approach, it is certainly not new: principle 15 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development agreed by all UN nations in 1992 states:

In order to protect the environment, the precautionary approach shall be widely applied by States according to their capabilities. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.

Given the furious debates about the reality of anthropogenic climate change over the last 30 years, one could be forgiven for thinking that evidential certainty is all that matters in most people’s minds. It is only recently that the BBC acknowledged it is no longer politically contentious to report anthropogenic climate change as fact. So although we have finally reached a point where the argument has been won with regards to evidence, it has unfortunately meant many wasted years which could have been avoided if the precautionary principle had been taken seriously. The painstaking accumulation of evidence of temperature rises and melting glaciers is of course important, but without this evidence we still knew enough to realise that pouring billions of metric tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere every year might just cause us some major problems. We really shouldn’t have needed ‘full scientific certainty’ before we acted.

Critics might argue that the precautionary principle encapsulates a deeply conservative attitude to the world which would stop innovation and change in its tracks. The industrial revolution, it might be argued, would have never have happened at all if the innovators of the time had been more cautious. Certainly the principle prompts us to ask the question of whether a given piece of technological innovation has more risks associated with it than benefits, and this in turn forces us to reflect on what it is we actually want out of ‘progress’. What exactly does a benefit look like? Is it really worth the risk of potential harms? None of this, however, necessarily means stasis. Perhaps we should see progress more as feeling your way across a dark room rather than striding forth with the illusion of 20/20 vision of the future. After all, risks are things we deal with in our everyday life quite happily without the need for scientific evidence. We don’t need to see research findings to tell us that speeding on a narrow road in an urban area is more likely to result in a traffic accident than traveling at a similar speed on a dual carriageway. Evidence can be helpful of course, and sometimes our initial judgments are awry, but if we have an inkling of danger we tend to err on the side of caution. In evolutionary terms, caution – and even over-caution – has allowed us to survive. On the macro or societal level, however, and with regard to technological changes that could potentially cause far more serious harm, we seem to throw caution to the wind, as if technological change is always good by definition. And there are further questions which are often skipped. Who will the technology benefit? Who will control it? And, if it is to be deployed, what is the best way to deploy it so the risks are minimised and the benefits maximised?

During the 1990s assumptions about the benign nature of the internet were taken for granted. It was generally accepted that by its very nature it would have a democratising influence. Few foresaw the emergence of unaccountable tech. giants who would in effect take control. It is, of course easy to be wise in hindsight, but there were voices warning of potential dangers. As Shoshona Zuboff shows in her book Surveillance Capitalism, a more cautious approach was being taken at the beginning but this soon got over-ruled by the rush for market dominance.

Science itself is a cautious enterprise. Surely this is an appropriate strategy when exploring the frontiers of knowledge, but caution can work both ways, identifying dangers as well as benefits, a point which comes out in the Rio declaration quoted above. Just because we have not reached scientific certainty about a danger does not mean there is no risk of harm. And as we have seen, it is so easy to make assumptions that we hardly notice. Absence of evidence of harm is not the same as evidence of harmlessness. Thalidomide, for example, was simply assumed to be safe for pregnant women. Risks can of course also be associated with not doing something, an issue that came up during the covid pandemic, when the balance was between the risks of not taking the hastily produced vaccines and any potential risk posed by the vaccine itself.

More generally, it’s clear that the precautionary principle goes together with a much needed ethical reset. Even without full blown deep ecology, we do need to start seeing ourselves as an integral part of nature rather than as dominating over it. This is simply a matter of humility. Decisions makers need perhaps to take an ethical lesson from the Hippocratic Oath which guides the medical profession.[2] The first priority should be ‘do no harm’. This of course means they cannot afford to wait for evidence of harm, since clearly by then the ethical prescription will have already been broken.

[1] In, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, chapter 2

[2] This is a suggestion made by Kate Raworth in, Doughnut Economics: How to Think like a 21st Century Economist, chapter 4