by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Marie Snyder

Will re-branding Covid help people start acting to protect themselves from it? Maybe we need an ad campaign to kick-start public health. Outside of judicial rulings and before marketing, we had religious leaders to remind us to the best ways to survive, and before that we had stories passed down for generations to help keep children safe from harm by altering their behaviour, like this one:

Will re-branding Covid help people start acting to protect themselves from it? Maybe we need an ad campaign to kick-start public health. Outside of judicial rulings and before marketing, we had religious leaders to remind us to the best ways to survive, and before that we had stories passed down for generations to help keep children safe from harm by altering their behaviour, like this one:

“Our parents told us that if we went out without a hat, the northern lights are going to take your head off and use it as a soccer ball. We used to be so scared!”

Unfortunately, those types of stories are unlikely to work on media-savvy kids today. They also seem immune to stories about going out without a mask, and being cautioned that the invisible microbes are going to infect your brain and body until you can’t get out of bed anymore. They’re not scared at all.

Except that one is true.

We don’t need to live in fear, but we do need a healthy wariness of the dangers of frostbite, drowning, cars, and pathogens. We train our kids to be careful near the road and near water. We watch out for them. Unfortunately, we’ve largely stopped doing that with pathogens, and children are paying the price.

We might think that stories of monsters won’t work, yet advertising is still able to convince us to want things we didn’t know existed five minutes ago. We need to market the virus differently. Read more »

by Gus Mitchell

In Henry VI, Shakespeare seems to have coined the expression “heart’s content.” The phrasemaking of King Henry is telling: “Her grace in speech”, he says of his Queen, “makes me from wondering, fall to weeping joys. / Such is the fulness of my heart’s content.”

Juxtaposing “wondering” to the joyous “fullness” of “content”, he describes the process of joy as an escaping of the potentially infinite vagaries of thinking; it is held in the intuitive knowing of the heart. To feel content, then, is to rejoice in a feeling of fulness beyond the need for further words, for further inputs or outputs, a fulness which depends, implicitly, on the felt presence of a pre-inscribed limit –– a container –– beyond which no more wanting or needing is possible.

Content derives from the Latin contentus (contained; satisfied) and continere (to hold together/enclose) – from the root com (with, together) and tenere (to hold). Content is a noun, a verb, an adjective, but common to all of these is the sense of something held, kept together, contained. It is a symptom of our inverted times that content has now means something radically alien. Content as an attainable feeling vanishes as the content of the internet proliferates.

Google “What is Content?” and you will encounter an infinitude of web pages explaining the concept of content marketing; the indispensability of superior content for your brand; how to use content strategically, on and on. The word itself is a blank: “Most businesses already engage in content marketing in some form by creating consumable content that is published on a public platform to generate brand awareness.” Read more »

That title reads like I have doubts about the current state of affairs in the world of artificial intelligence. And I do – who doesn’t? – but explicating that analogy is tricky, so I fear I’ll have to leave our hapless captain hanging while I set some conceptual equipment in place.

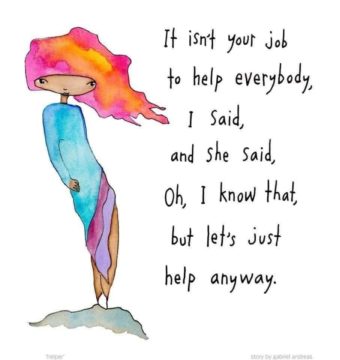

First, I am going to take quick look at how I responded to GPT-3 back in 2020. Then I talk about programs and language, who understands what, and present some Steven Pinker’s reservations about large language models (LLMs) and correlative beliefs in their prepotency. Next, I explain the whaling analogy (six paragraphs worth) followed by my observations on some of the more imaginative ideas of Geoffrey Hinton and Ilya Sutskever. I return to whaling for the conclusion: “we’re on a Nantucket sleighride.” All of us.

This is going to take a while. Perhaps you should gnaw on some hardtack, draw a mug of grog, and light a whale oil lamp to ease the strain on your eyes.

What I Said in 2020: Here be Dragons

GPT-3 was released on June 11 for limited beta testing. I didn’t have access myself, but I was able to play around with it a bit through a friend, Phil Mohun. I was impressed. Here’s how I began paper I wrote at the time:

GPT-3 is a significant achievement.

But I fear the community that has created it may, like other communities have done before – machine translation in the mid-1960s, symbolic computing in the mid-1980s, triumphantly walk over the edge of a cliff and find itself standing proudly in mid-air.

This is not necessary and certainly not inevitable.

A great deal has been written about GPTs and transformers more generally, both in the technical literature and in commentary of various levels of sophistication. I have read only a small portion of this. But nothing I have read indicates any interest in the nature of language or mind. Interest seems relegated to the GPT engine itself. And yet the product of that engine, a language model, is opaque. I believe that, if we are to move to a level of accomplishment beyond what has been exhibited to date, we must understand what that engine is doing so that we may gain control over it. We must think about the nature of language and of the mind.

I still believe that. Read more »

A majestic Black Kite outside the 5th floor window of a hotel in Karachi.

by Bill Murray

Petro Oliynik wore a flag draped around his shoulders like a cape and didn’t speak. If it wasn’t an act, it was at least a presentation. You don’t often meet a man as unusual as Petro Oliynyk and the truth is, I haven’t really met him either. Maybe better to say I once accompanied him on his daily rounds.

Oliynik’s legend describes him as a simple stallholder in a market in Lviv who was drawn in the pursuit of democracy to the Maidan in Kyiv’s 2014 Revolution of Dignity. In the noble pursuit of righteousness, the story goes, he found his calling at a mansion outside Kyiv, and never left.

Four years ago Petro Oliynyk escorted three of us on a tour through that building north of Kyiv, popularly known as the Honka House. They call it that because the contractor was a Finnish builder of log homes called Honka, but that’s not why you tour it. You tour it because it’s a monument to inveterate corruption and bad taste – to everything Ukraine has been trying to leave behind.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a real human tragedy, doubly so because of where Kyiv was headed. I visited Kyiv twice these last ten years, in 2013 and 2019, and the differences between the first and second trips tell a story. Read more »

by Nils Peterson

I went to graduate school at Rutgers in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Rutgers had a fine University Chorus that sang one concert a year with a New York Orchestra at Carnegie Hall and one concert a year with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Though my scholarly friends scoffed at such a waste of time, I had the chance to sing with some of the great conductors, Eric Leinsdorf, for instance, and, of course, Eugene Ormandy.

My last semester in New Jersey, we sang the Brahms German Requiem with the Philadelphia Orchestra. It was a transcendent thrill. I had loved the piece as a listener, but now I had the chance to go so deeply inside it as a singer (and spend a long weekend in Philadelphia to boot). Not long after our last performance, I got married and set out across country for California and my first full-time teaching job at San Jose State, not yet a university. The year was 1963.

I arrived in San Jose dead broke. My wife and I had money for one night in a hotel (all night long, the same noisy cars circled round and round) and then we had to find a place to rent the next day or we would have had to use part of our month-in-advance rent money. Incredibly, we found a cottage on a rich man’s estate overlooking the valley. We were allowed to use the swimming pool in the yard. The one in his living room was for his family alone. We had also gotten our first credit card, a Bank America one with a $200 limit. (Well, my pay was $6,600 a year.) We maxed it out on a $195 hi-fi set.

I found that I enjoyed teaching even though I had three sections of composition. My fourth class was a survey of English Literature. Originally, I was scheduled to have 4 composition classes, but the new head of the department took pity on me and split one of the senior professor’s class. In gratitude, I think I tried to squeeze a graduate seminar into each class, but the students seemed to like it and me.

One November morning, bright and shiny like the November morning I’m typing this in, I walked out of my English Lit class to the news that President Kennedy had been shot. Read more »

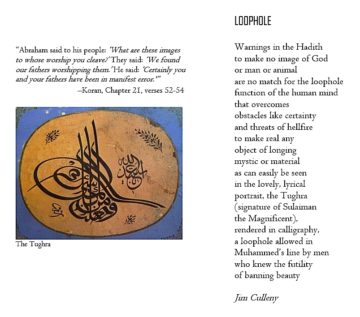

by Shadab Zeest Hashmi Masjid Al Aqsa, or The Far Mosque of Jerusalem, as the Quran calls it, is emblematic of the spirit of compassion and transcendence for Mevlana Rumi. “A heart sanctuary,” in the words of Rumi in his poem “The Far Mosque,” Al Aqsa represents a conquest over the egoistical desires of dominance, greed, vanity, violence and supremacy. It is held together by the sacred energy of merciful love, even “the carpet bows to the broom/the door knocker and the door swing together/like musicians.”

Masjid Al Aqsa, or The Far Mosque of Jerusalem, as the Quran calls it, is emblematic of the spirit of compassion and transcendence for Mevlana Rumi. “A heart sanctuary,” in the words of Rumi in his poem “The Far Mosque,” Al Aqsa represents a conquest over the egoistical desires of dominance, greed, vanity, violence and supremacy. It is held together by the sacred energy of merciful love, even “the carpet bows to the broom/the door knocker and the door swing together/like musicians.”

There is an expansiveness in Rumi’s poem that mirrors the place. I recall the embrace of the silent hours as I sat on the russet prayer carpets of Al Aqsa a few years ago– the wide doors, stained-glass windows, voices of children braided with the rhythmic recitation of the Qura’n, the scrawny birds covered in holy dust, stones sculpted by mythic time. I also recall stepping out of one of the fifteen gates of Al Aqsa, into a scene from a war movie, IDF soldiers with guns in all the storied alleys, and all the thresholds of sacred sites.

Jerusalem is no heart sanctuary. It is “the bitterness of two hundred winter-bare olive trees fallen/in the distance,” as a line from a poem by the Palestinian-American poet Deema Shehabi says. Her poem “In the Dome of the Rock” haunts me; it reflects the soul of Palestine, the soul of Al Aqsa, the guardian that has given this site of ascension its very blood. Shehabi continues with the unforgettable persona: “her exhausted/scars will gleam across her overly kissed forehead. She will ask you to come closer, and when you do,/ she will lift the sea of her arms from the furls/ of her chest and say: this is the dim sky I have/ loved ever since I was a child.” Read more »

by Tim Sommers

One time, this guy handed me a picture of him and said, ‘Here’s a picture of me when I was younger.’ Every picture is of you when you were younger. – Mitch Hedberg

There’s synchronic identity, what makes you, you at a particular moment in time – say, now. And there’s diachronic identity, what makes you, you over time. For example, why are you now the same person as when you were twenty-five years old or five (if you are)? These two perspectives – synchronic and diachronic – are deeply interdependent, of course, but philosophers tend to focus on diachronic identity since what is essential to you being you is, presumably, whatever it takes for you to continue to exist. Here are some theories.

You are your soul.

The trouble with this theory is not that it usually has a religious basis. That might be trouble later, but initially the trouble is that it is not very helpful. I am my soul. So, what’s my soul? Is the soul some mysterious, ghostly thing or a Platonic form or is it just whatever is essential to who I am? If the answer is that the soul is whatever is essential to who I am, this seems like just a restatement of the question.

Keep in mind, the great innovation of Christianity was not the soul, an idea that’s been around at least since Plato and Aristotle (who thought we had three souls). The Christian innovation was bodily resurrection.

You are your ego.

The ego may just be the secular soul. Descartes’ version of the ego theory, the most influential, is that a person is a persisting, purely mental, thing. But like the soul it’s hard to unpack the ego in an informative way. It is whatever unifies our consciousness. We survive as the continued existence of a particular subject of experiences, and that explains the unity of a person’s life, i.e., the fact that all the experiences in this life are had by the same person. This is circular, of course. Further, on this view, what happens if I fall into a dreamless sleep? Or get hit on the head and black out? Go in and out of a coma? Am fully anesthetized? When I wake up and start having experiences again, how do I know I am the same ego? How do I know that the ego is a persistent thing at all? Later, we will see what Hume has to say about this.

In the meantime, we are going to need a better theory of the ego or soul before either is going to be useful as a theory of personal identity. Read more »

by Jonathan Kujawa

In 2016, here and here at 3QD, we talked about some of the inherent paradoxes in democratic voting [1]. We discussed Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem, along with related results like the Gibbard-Satterthwaite Theorem. They tell us that there is no way to convert the individual preferences of the voters into a single group preference that doesn’t also conflict with some simple, commonsense guidelines that we can all agree are reasonable. Things like “No dictators.” And “If everyone prefers Candidate X to Candidate Y, then Candidate Y never beats Candidate X.”

In 2016, here and here at 3QD, we talked about some of the inherent paradoxes in democratic voting [1]. We discussed Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem, along with related results like the Gibbard-Satterthwaite Theorem. They tell us that there is no way to convert the individual preferences of the voters into a single group preference that doesn’t also conflict with some simple, commonsense guidelines that we can all agree are reasonable. Things like “No dictators.” And “If everyone prefers Candidate X to Candidate Y, then Candidate Y never beats Candidate X.”

Certainly, voters are sometimes irrationally motivated. I know of an otherwise reasonable mathematician who asked a colleague to vote on their behalf in a departmental chair election. Above all else, this mathematician did not want Faculty Member Z to be elected department chair. They gave their colleague two lists of all the eligible faculty in the department; each list was in a very carefully chosen order. The first list was ordered by the mathematician’s actual preference for who should be elected chair. This list was to be used only if Faculty Member Z wasn’t on the ballot. The second list was ordered according to the mathematician’s best 4D chess assessment of who was most likely to beat Faculty Member Z in a head-to-head election. That list would be used if Faculty Member Z was on the ballot. In the ideal election system, there should be no need for the second list. But strategic voting is very much a thing in elections.

You might assume such paradoxes are due to the vagaries of humanity. From what I can tell, most human minds are filled with a circus of chaos monkeys that are impossible to predict. Imagine describing the here and now to a 2016 version of yourself. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

John von Neumann emigrated from Hungary in 1933 and settled in Princeton, NJ. During World War 2, he contributed a key idea to the design of the plutonium bomb at Los Alamos. After the war he became a highly sought-after government consultant and did important work kickstarting the United States’s ICBM program. He was known for his raucous parties and love of children’s toys.

Enrico Fermi emigrated from Italy in 1938 and settled first in New York and then in Chicago, IL. At Chicago he built the world’s first nuclear reactor. He then worked at Los Alamos where there was an entire division devoted to him. After the war Fermi worked on the hydrogen bomb and trained talented students at the University of Chicago, many of whom went on to become scientific leaders. After coming to America, in order to improve his understanding of colloquial American English, he read Li’l Abner comics.

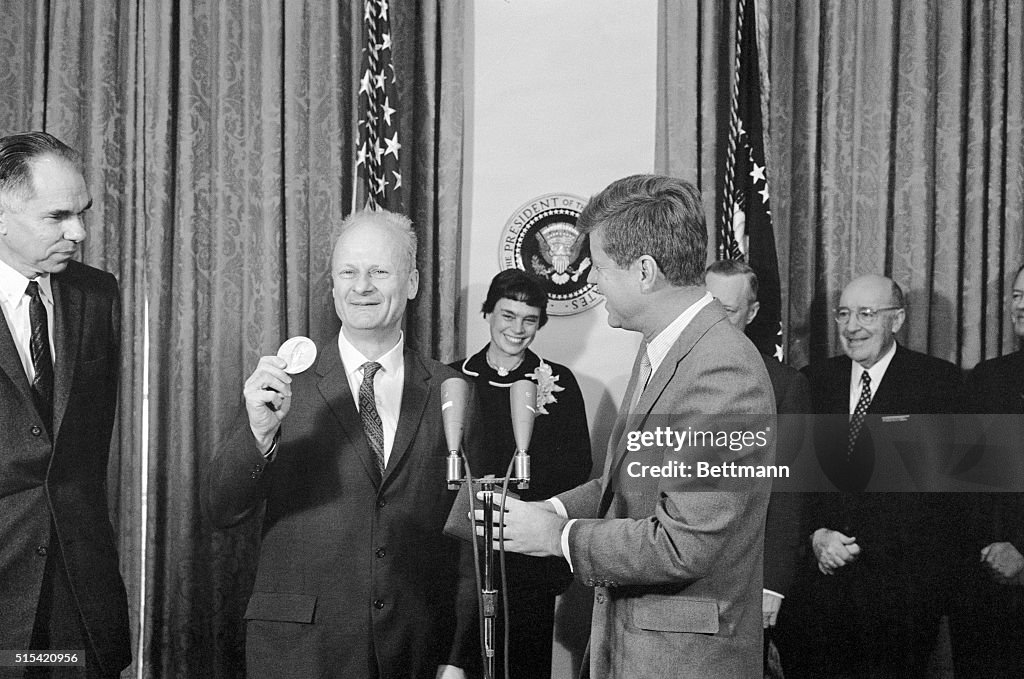

Hans Bethe emigrated from Germany in 1935 and settled in Ithaca, NY, becoming a professor at Cornell University. He worked out the series of nuclear reactions that power the sun, work for which he received the Nobel Prize in 1967. During the war Bethe was the head of the theoretical physics division of the Manhattan Project. He spent the rest of his long life working extensively on arms control, advising presidents to make the best use of the nuclear genie he and his colleagues had unleashed, and advocating peaceful uses of nuclear energy. He was known for his hearty appetite and passion for stamp collecting.

Victor Weisskopf, born in Austria, emigrated from Germany in 1937 and settled in Rochester, NY. After working on the Manhattan Project, he became a professor at MIT and the first director-general of CERN, the European particle physics laboratory that discovered many new fundamental particles including the Higgs boson. He was also active in arms control. A gentle humanist, he would entertain colleagues through his rendition of Beethoven sonatas on the piano.

Von Neumann, Fermi, Bethe and Weisskopf were all American patriots. Read more »

by Jerry Cayford

A friend of mine covers his Facebook tracks. He follows groups from across the political spectrum so that no one can pigeonhole him. He has friends and former colleagues who, he figures, will be among the armed groups going door to door purging enemies, if our society breaks into civil anarchy. He hides his tracks so no one will know he is the enemy.

That trick might work for the humans, but artificial intelligences (AI) will laugh at such puny human deceptions (if artificial intelligence can laugh). When AI knows every click you make, every page you visit, when you scroll fast or slow or pause, everything you buy, everything you read, everyone you call, and data and patterns on millions like you, well, it will certainly know whom you are likely to vote for, the probability that you will vote at all, and even the degree of certainty of its predictions.

All of that means that AI will soon be every gerrymanderer’s dream.

AI will know not just the party registrations in a precinct but how every individual in a proposed district will (probably) vote. This will allow a level of precision gerrymandering never seen before. There is only one glitch, one defect: with people living all jumbled up together, any map, no matter how complex and salamander-looking, will include some unwanted voters and miss some wanted ones. To get the most lopsided election result possible from a given group of voters—the maximally efficient, maximally unfair outcome—the gerrymanderer has to escape the inconvenience of people’s housing choices. And since relocating voters is not feasible, the solution is to free districts of the tyranny of voter location. The truly perfect gerrymander that AI is capable of producing would need to be a list, instead of a map: a list of exactly which voters the gerrymanderer wants in each district. But that isn’t possible. Is it? Read more »

by Christopher Horner

Why do we value art? I am going to suggest that a large part of the answer is to do with its unique power to disclose and convey areas of our lives unavailable to us though other means. Art, on this account, is a kind of communication, and kind of act: something performative – a communication that makes something happen, in a way that eludes ordinary discourse.

By ‘ordinary’ here I mean the kind of communication delivered by language when it is used to convey concepts: ranging from the most banal everyday speech to the most rarefied theory. Of course, ordinary speech acts themselves have a performative quality too – we don’t just communicate information through language, but make things happen, make requests, (‘shut the door’, ‘the meeting is over’ ‘help me!’). Moreover we use our bodies, tone of voice, emphasis and more: and the conceptual content may not even be what matters, especially when something isn’t banal, but matters greatly: moments of grief or joy, for instance. A gesture, a tear, or just silence may be more eloquent than words. It is this ‘beyond’ in our imperfect communications, that hint at what art can do. Art aspires to a more perfect communication: one that takes us beyond the confines of the lonely self. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by O. Del Fabbro

If a city could be an organism, then Kherson in Eastern Ukraine would be a sick body. For eight months, between March and November 2022, Kherson was occupied by Russian forces. Kidnapping, torture, and murder – in terms of violence and cruelty, Kherson’s citizens have seen it all. Today, even though liberated, the port city on the Dnieper River and the Black Sea is still being regularly bombarded: a children’s hospital, a bus stop, a supermarket. Even though freed, how could this city ever heal?

If a city could be an organism, then Kherson in Eastern Ukraine would be a sick body. For eight months, between March and November 2022, Kherson was occupied by Russian forces. Kidnapping, torture, and murder – in terms of violence and cruelty, Kherson’s citizens have seen it all. Today, even though liberated, the port city on the Dnieper River and the Black Sea is still being regularly bombarded: a children’s hospital, a bus stop, a supermarket. Even though freed, how could this city ever heal?

One of Kherson’s citizens is Andryi. As soon as the Russians left, Andryi and his friends started with humanitarian work. For months the former car mechanic had no job. He rather helped others. When the pastor of his church found out about Andryi’s skills to repair roofs, he gave him some money and assignments. “My friend and I started with a house in which an old grandmother and her son lived.” Before Andryi and his friend started their work, three different groups looked at the roof but did not dare to repair it, because the Russians were only four hundred meters away, on the other side of the Dnieper River, waiting to kill humanitarian aid workers. “We decided to do it, and we did it. Praise the Lord, nothing happened.” Three days later, the roof was finished.

While repairing roofs Andryi has been exposed, both indirectly or directly, to a variety of weaponry: mortars, snipers, rockets, you name it. “When we repaired roofs, artillery fire was constantly active. Once, we saw phosphorous bombs in the near distance, then we hid in the basement.” The last roof was the scariest experience. Some of the material that Andryi and his partner use is a plain white awning, easily detectable by the Russians. Being only one kilometer away, the Russians bombarded Andryi and his friend with mortars, but luckily, they missed. “That was scary, but they did a bad job in trying to hit us.” In total, Andryi counted twenty-six explosions. “It was frequent, loud, and very close.” When talking about his war experience, Andryi has, as many Ukrainians, a dry and succinct way of expressing himself. “You realize that you can get hit, when you hear the bomb exploding.”

Friends, family, donations via social media, the pastor, and the members of his church helped to buy materials such as nails, wood and so on, but at some point, Andryi and his friend ran out of money. He then simply helped the military by using his skills as a car mechanic. He built a heavy machine gun on the back of an old Rada, or repaired the sewage system of a village in the countryside near Kherson. Read more »

by Ethan Seavey

Exile is on my mind and there’s a large full moon above my head I cannot see through the clouds.

I am part of a family of three exiles who are doing it again, recovering after exile, and working hard to stay together. Our shared communities have dropped us for the third time and it feels like I finally recognize the pattern we’ve always fallen into :

1) Find a community that embraces us because it excludes others; and 2) get rejected when we grow to learn that we have become the others.

When I came out as gay in 2015 my family stopped going to Church, specifically the one where we had been attending weekly (with few exceptions) for somewhere around a decade.

It was a personal decision for each one of us. It was an effort to support me. It was also a social decision. While this Church was more progressive than others, it was still a Catholic Church. It seemed to me that priests were required to spend a Sunday sermon every year talking about how being gay is a sin; sometimes hiding it behind the idea that being gay was not a sin so long as you never acted on it.

Many people within that Church remained close friends. They’d ask why we’d stopped attending and I was the reason. It didn’t distance most of our friends, but I remember my younger sibling was forbidden from spending time with one of their friends outside of the friend’s home, because the friend’s mom saw me as a bad influence. Read more »

by Oliver Waters

Two popular books released this year have breathed new life into the ancient debate over whether we have free will.

Two popular books released this year have breathed new life into the ancient debate over whether we have free will.

In Free Agents, Kevin Mitchell argues that we do, and in Determined, Robert Sapolsky argues that we don’t. To be blunt, on the big issue at hand – Mitchell is right and Sapolsky is wrong.

Despite this, Sapolsky does make a compelling case however for not excessively condemning or praising people for their decisions. The sections of his book that focus on well-evidenced pathologies that drive criminal behaviour and why policymakers should take these into account are insightful and engagingly written.

The problem is that Sapolsky extrapolates from this to an outrageously untenable position:

“We are nothing more or less than the cumulative biological and environmental luck, over which we had no control, that has brought us to any moment.”

Sapolsky mistakenly infers that because there are many factors beyond your control that influence your decision-making, those factors entirely caused your decision. But all that is needed for a reasonable concept of ‘free will’ to get off the ground is that part of the decision was within your control. This of course begs the question whether a meaningful entity called you actually exists, which has causal power beyond the sum its parts. Read more »