by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Joseph Shieber

In one of those strange cases of synchronicity that occasionally arise in publishing, two books – issued within a year of each other – appeared on the same under-researched topic, a discussion of the lives and intellectual impact of the philosophers G. E. M. Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Iris Murdoch, and Mary Midgely. The first of the books to appear, The Women Are Up To Something, by Benjamin Lipscomb, traces the lives of all four philosophers, with a central focus on their training at Oxford and their formative years as budding professional philosophers, but with a discussion of the full scope of their intellectual lives. The second book, Metaphysical Animals, by Clare Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman, is more tightly focused on the period in which the four philosophers found their professional footing; whereas Lipscomb’s book takes the reader up to Mary Midgely’s death in 2018, Mac Cumhaill and Wiseman end their narrative in the 1950’s.

Both books are worth reading, though Lipscomb’s is perhaps the more engagingly written of the two. Lipscomb organizes each of the main chapters around one of the philosophers, making it easier to follow the narrative, whereas Mac Cumhaill and Wiseman hew more closely to chronology to structure their account, tracking each of the philosophers’ developments in every chapter, making it sometimes more difficult to keep track of all of the names of the secondary characters. Despite covering much of the same ground, both books often treat the same anecdotes and philosophical content in slightly different ways – and have sufficient non-overlapping content – so that I am happy that I read both books.

Both books also share a similar weakness, one perhaps unavoidable in works aimed at a broad, non-specialist audience. It’s that they tend to flatten out the discussion of deep philosophical questions, leaving readers with the impression that the debates of the past have been settled. In the case of both books, the suggestion is that the story of Anscombe, Foot, Murdoch, and Midgely is the story of how this band of outsiders could push back against the ascendancy of the fact-value distinction in ethics. Read more »

by Jochen Szangolies

There seems no obvious link between tall war-tales, shared among a circle of German aristocrats in the 1760s, and quantum mechanics. The former would eventually come to form the basis of the exploits of Baron Münchhausen, the partly fictionalized avatar of Hieronymus Karl Friedrich, Freiherr von Münchhausen, famous for his extravagant narratives, while the latter is the familiar, yet vexingly incomprehensible, theory of the ‘microscopic’ realm developed more than 150 years later. Both, however, seem to equally beggar belief: which is stranger—riding a cannonball across a battlefield (and back), or seemingly being in two places at once? Reconnecting a horse bisected by a falling gate, or deciding the fate of a both-dead-and-alive cat by opening a box?

But beyond mere bafflement, the stories of Münchhausen’s exploits have inspired a philosophical conundrum relevant to the question of quantum reality. Perhaps the Lügenbaron’s most famous story, it concerns his getting trapped in the swamp on his horse, a conundrum which is solved by pulling the both of them out by his own plait of hair.

The power of this image was appreciated by Friedrich Nietzsche, who in Beyond Good and Evil likened the concept of ‘free will’ to being a causa sui, “with a courage greater than Munchhausen’s, pulling yourself by the hair from the swamp of nothingness up into existence”. But in its most famous formulation, due to the German philosopher Hans Albert, who died last week at the venerable age of 102, it comes in the form of the Münchhausen-trilemma. Any attempt at finding a final justification, according to Albert, must end in either of the following options:

Infinite regress: whatever is supposed to yield this justification must be justified itself (turtles all the way down)

Circularity: the justification of some proposition presumes that very proposition’s truth (the turtle stands on itself)

Dogma: the regress is artificially broken by postulating a ‘buck-stops-here’ justification that is assumed itself unassailable and without need for further explanation (the final turtle is supported by nothing)

Each of the above seems to frustrate any attempt at finding any sort of certain ground to stand on—and, lacking Münchhausen’s ability to drag ourselves out by our own hair, sees us firmly bogged down in the mire of uncertainty. An infinite regress will never reach its conclusion, thus, like a parent frustrated with an endless series of ‘Why?’, we may be tempted to cut it short by an imagined regress-stopper—‘because I/God/the laws of physics say so’, but just because the journey stops, doesn’t mean we’ve arrived at our destination.

What can be done in the face of the trilemma? Read more »

by Rebecca Baumgartner

A few months ago, I was eating dinner at a restaurant and the manager stopped by to see how I was doing. When he saw me reading War and Peace, we got into a conversation about what the book was about, why it was so long, and whether it was worth it (the answer to the last one is “yes,” by the way!). After a few minutes of conversation, he assured me he would get it and try to read it. And then he comped my meal.

I love it when things like that happen. I don’t mean getting free stuff (although that does happen sometimes – just the other day I had a cashier at Target randomly give me a $5 gift card because he liked my Legend of Zelda shirt and was happy to find a fellow fan). What I really mean is the surprisingly pleasant, spontaneous interactions we have with strangers, acquaintances, and other “weak ties,” to use the sociological term. For example, the other day I showed up at my favorite Italian restaurant and before I’d even sat down, the waiter had brought me my wine and informed me that he’d already put my order in.

What amazes me is just how meaningful and interesting and life-affirming these exchanges feel. It feels good to be recognized and remembered, even in the context of trivial things like pizza and coffee (which are actually not that trivial, in my opinion). Baristas remembering your name, a coworker remembering your birthday or pet’s name, someone asking after the random body part that was hurting the other day – all of these are dopamine hits for our socially wired brains. Each one says You have a community. You’re safe. This person has your back. Of course, in reality it’s not that simple, but in a very significant sense, it almost doesn’t matter if those beliefs are literally true or not. The simple fact that your brain holds them has a psychologically healthy and protective quality all its own. Read more »

by Barry Goldman

I started this series of articles by claiming the adoption of the rule of law was the second biggest mistake in the history of the human race. I modeled my claim on Jared Diamond’s assertion that the biggest mistake in human history was the adoption of agriculture. I said the move from face-to-face resolution of disputes by people who knew each other to a bureaucratic system of written rules administered by strangers did not advance the cause of justice. I explained some of the most serious defects of the legal system here, here, here, and here. Essentially, the system of written laws distracts us from our real disputes and prevents us from proposing particularized, nuanced resolutions; the rich and powerful control the process; and the system pays for itself by extracting value from the disputants. Then I promised I would propose an alternative.

The alternative is that we resolve our disputes the way our ancient ancestors did, by talking to each other. This is not just historical romanticism. The idea that talking to each other is a good way to solve problems has support in modern psychology. Consider, for example, “the illusion of explanatory depth.” Here’s a question: On a scale of 1 to 7, how well do you understand how a zipper works?

Most people say they know how a zipper works. You pull the tab up, the little teeth fit together, and the zipper closes. You pull the tab down, the little teeth separate, and the zipper opens. Right. But that describes what a zipper is. Everybody knows what a zipper is. The question is whether you know how it works. Please describe in as much detail as you can all the steps involved in a zipper’s operation.

Finished?

Okay, now try the first question again. On a scale of 1 to 7, how well do you understand how a zipper works?

What you have just demonstrated is the illusion of explanatory depth. It isn’t just you, and it isn’t just zippers. We all believe we understand much more than we do. There are books on the subject. One of the most accessible is The Knowledge Illusion by Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach. Read more »

by David Kordahl

While grading papers last week, I turned on Max (the streamer formerly known as HBO) and watched The Insurrectionist Next Door. This documentary was made by Alexandra Pelosi, the daughter of Rep. Nancy Pelosi. I’d read a little about the film beforehand, and I was curious how the younger Pelosi would find a way to profile her subjects—characters in various amounts of trouble with the law due to their actions at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021—without her kinship with the elder Pelosi getting in the way. But this connection turns out to be the central gimmick, and Pelosi makes no secret of it, casting herself as a shocked diplomat to Trump’s deplorables.

“What do you think of your dad’s song, ‘Fuck Joe Biden’?” she asks an older daughter in one scene as Dad, a White rapper with the words PROUD BOY tattooed across his forehead, sits with a younger child on his lap. Pelosi presents herself as frankly confused by the Trumpists. The White rapper, Billy Knutson, is thought by his family to be a good dad and good husband, and we watch his wife and children cry as they leave him at the prison for a six-month stint.

All leads of The Insurrectionist Next Door face, or have already served, time in prison. Another interviewee, the ex-pornographer Felipe Marquez, is shown baking a cake for Pelosi at his home in Fort Lauderdale, FL, where he is under house arrest. As Marquez tells his story, Pelosi refuses to believe it. “So a hooker broke up with you and that turned you into a Christian conservative?” she asks.

“I thought she was just a regular woman who would have a family with me, and we would watch conservative news together,” says Marquez.

Pelosi presses him on this, exasperated. “You’re telling me that the left is responsible for your prostitute girlfriend leaving you, and therefore you took it out on the left by storming the capitol and participating in an insurrection?”

“Men are weird,” he says, frowning while stirring in the eggs. Read more »

by Michael Liss

My brother need not be idealized, or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life; to be remembered simply as a good and decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it. —Edward M. Kennedy, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York City, June 8, 1968

Bobby Kennedy’s casket, covered by an American flag, attended to by the powerful and the humble. In the audience, the Kennedy clan, the Kennedy brain trust, friends and admirers and rivals. Lyndon Johnson, presiding over his second Kennedy funeral. Richard Nixon and Nelson Rockefeller. Hubert Humphrey and Eugene McCarthy. When the service concluded, the casket was taken to Penn Station. From there, a private train, carrying over 700 mourners and reporters, headed through big cities and small towns to Washington. Watching it pass, more than a million common folks, young and old, black and white, some there for the spectacle, most to pay their respects. Then to Arlington, to be buried near his older brother Jack.

Now what? Politics is like a terrible machine, always lurching forward, soulless and with no conscience. The political world stopped for Robert F. Kennedy for a week—because it would have been unseemly not to—but that’s all it stopped for. Bobby Kennedy was dead, but his rivals were alive and wanted the prize. The relentless counting of delegates ran parallel to the math of mourning and, quickly, passed it by. There were still primaries and state nominating conventions. There were speeches to give, doors to be knocked on, commercials to create, interviews, telethons, bumper stickers, and, more cold-bloodedly, wooing of the delegates Bobby had won, and perhaps even some of his team.

There was a complicated three-dimensional chess to this. Where would Bobby’s voters and Bobby’s team go? McCarthy, with his “pure play” anti-war message, wasn’t a perfect fit, either on ideas or demographics. Bobby’s campaign was more than that. He’d brought a passion for economic and social justice, with a special connection to working class and minority voters. Read more »

by R. Passov

Mary Jane, when she lived at the end of my block, would periodically warn me that the giant sugar maple in front of my house was not doing well. Water it, she would say and get it tended. She was probably in her early eighties when she first offered that advice. As I got to know her, I discovered she had advice on many subjects.

Her grandson and my son played together on the local sports teams, just as Mary Jane’s five sons had. Once she overheard my son mention how cold his bedroom was. That prompted her to come by with an armload of newspaper which she said, if stuffed under my son’s mattress, would help. It did help. I stopped being stingy and let the house warm up.

On a cold December day I found her standing at the end of my driveway, dressed in all black but missing a glove. Mary Jane, I said, now I know what to get you for Christmas – a glove.

She flew right past my attempt at humor. That won’t be necessary, she said. I’m going to Florida next week. You know, she explained, there are a lot of old people there so if you go to a thrift shop the clothes you can buy are hardly worn. I got this whole outfit at one and intend to go back and get a glove.

Not long after telling me where she intended to find a single glove, she rather petulantly asked why, if I had been divorced for over a year, had I not asked her over for dinner. She was thirty years my senior and the matriarch of our block. I was flattered. This Saturday, I said, if you’re free. I am, she said, and I’d like a steak, potatoes and broccoli.

She was my first post-divorce date. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Yarn Art on The Mass Ave Bridge, July 2014.

Sughra Raza. Yarn Art on The Mass Ave Bridge, July 2014.

Digital photograph.

by Rafaël Newman

Every human generation has its own illusions with regard to civilization; some believe that they are taking part in its upsurge, others that they are witnesses of its extinction. In fact, it always both flames up and smoulders and is extinguished, according to the place and the angle of view. —Ivo Andrić (tr. Lovett F. Edwards)

I was accompanied through the last week of October by a succession of Bosnians: Adnan introduced me to Sarajevo; Emir and Senad took me through Eastern Bosnia; Ajla and Merima led me down the valley of the Neretva River to visit the dervish monastery at Blagaj and the reconstructed bridge at Mostar; and Ahmo, the stoical busman employed by Funky Tours, drove me three 12-hour days in a row through the multiethnic heartland of former Yugoslavia.

It was the time of year when I usually accompany my partner, Caroline Wiedmer, a professor of Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies at Franklin University Switzerland, and a group of students on Academic Travel, the extramural component of a semester-long course with an international theme. (I have written about past travels here, here, and here.) “CLCS 220: Inventing the Past,” a course in memory studies Caroline has offered many times since 2007, has typically focused on French, German, and Polish sites of Holocaust remembrance, an early specialty of hers; this year it was devoted to Sarajevo, as well as to other towns in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and to a study of the culture of memory there, nearly thirty years after the Dayton Agreement put an end to the violence and atrocities surrounding the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Our daughter, Hella Wiedmer-Newman, was also along on the trip. Her work as a doctoral student in art history at the University of Basel focuses on art and memorialization in postwar ex-Yugoslavia, and this, together with her growing proficiency in the Bosnian language, made her an obvious choice to lead some of the on-site seminars in Sarajevo. Read more »

by Marie Snyder

Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ, was originally published in 1995 but more recently updated in a 25th anniversary edition in 2020. Well, he added a new introduction, but no study or concept in the book was updated despite huge changes in our lives since then and tons of new studies with updated technology. It’s kind of refreshing to read a book about the problem with kids today without a single mention of phones, but it feels a little sloppy. Goleman is a science journalist without a clinical practice in psychotherapy as far as I can tell. While his book is about how to be smart according to the front cover, it’s also being used in psychotherapy. It’s a fast, engaging read, but I have some concerns about the content and application.

Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ, was originally published in 1995 but more recently updated in a 25th anniversary edition in 2020. Well, he added a new introduction, but no study or concept in the book was updated despite huge changes in our lives since then and tons of new studies with updated technology. It’s kind of refreshing to read a book about the problem with kids today without a single mention of phones, but it feels a little sloppy. Goleman is a science journalist without a clinical practice in psychotherapy as far as I can tell. While his book is about how to be smart according to the front cover, it’s also being used in psychotherapy. It’s a fast, engaging read, but I have some concerns about the content and application.

The book outlines the need for emotional intelligence (EI) to be overtly taught to children, explains the psychoneurology of EI, argues for the primacy of emotional intelligence for success, adds in the need for emotional supports, and ends with a call for parents to be better educated as well. The principle underlying Goleman’s text is that there are four specific domains, adapted from Salovey & Mayer, that emerge from the activity of our brain circuits that have more of an impact on our general well being than does our intelligence: self-awareness, self-management (formerly motivation and self-regulation), empathy, and skilled relationships. Goleman explains that people will be better off emotionally, relationally, and vocationally if they develop their emotional intelligence to identify and understand their feelings as they happen, manage them effectively, understand other people’s feelings, and relate to others more positively. With a calm mind, people can make better decisions, which positively affects all other aspects of their life. Goldman has used these domains to help to develop educational programs to teach children Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) in the schools through the CASEL organization. I feel like it goes without saying that being able to manage our emotional experiences helps in other aspects in our lives, so I’m all in at this point. Read more »

by Gus Mitchell

When we hear the constant cry–that we need “better stories”–there is surprisingly little followup. How or where we are going to find them, how are they going to be told? The “how” is the thing.

Knowledge, our fetishizing of knowledge, our demand that we have an opinion on every new fact makes us utterly helpless, leaves us feeling that we don’t really “understand” any of it at all. Our most constant daily ritual is that of the scroll, the instantaneous return to the temple of information.

In our lack of knowledge and our lack of power, we can at least choose the stories we want to be told. Indeed, we have more choice than ever before. Why then, are we constantly told that our suiciding world’s crisis is “a storytelling crisis?”

Storytelling is a power relationship, a good, beneficial, and safe kind of power. The power is that the storyteller knows something which you do not, and which you want to lean forward to hear, to catch.

Nietzsche’s Last Man has no one to tell him a story. The Last Man is stuck in a world of cold realism, which paradoxically keeps seeming less and less real, less comprehensible.

Is the problem partly that the only civilization we have, which still shrilly declares itself to be the only possible arrangement of things, the last word on a realistic way of living, good or bad, is, in fact, fundamentally fantastical? (Unreal?) Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Akim Reinhardt

No longer eating meat was similar to no longer believing in God. I can’t pinpoint a moment when it ended, for abstinence did not come upon me suddenly. Rather, what had once been a bedrock of my existence slipped away after years of contemplation. Some time in 1995, I realized it was no longer part of my life. This coincided with me moving to Nebraska, which did not make giving it up any easier. Meat, that is. God was a few years earlier.

But why?

More and more it seemed to me that the differences between dogs and cows and monkeys and horses and pigs and cats and us were not so vast. Mammals were too much like each other for me to feel okay about killing and consuming them for pleasure, as it were, since I didn’t need to eat meat. If it were 18th century America, of course I would. What alternative would I have? But with the 21st century rapidly approaching, meat was a luxury I could forego. And it felt hypocritical to ask someone else, anonymous minimum wage workers on slaughterhouse assembly lines, to slay and gut animals for me if I were now unwilling to do that myself.

I still enjoyed fishing once in a rare while, so I went on eating seafood. Fish still seemed like creatures from another world. But I could look most any mammal in the eye and see a little bit of myself in there.

Or a piece of you. Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

In C. Pam Zhang’s new novel Land of Milk and Honey, an agricultural disaster in the Midwest sends clouds of particulates into the atmosphere. Like nuclear winter, the toxic smog suffocates 95% of the plant and animal species on the planet. Famine and societal collapse soon follow~~ and not surprisingly, the super-wealthy start making plans. The fat cat in the novel begins by buying a beautiful mountaintop in Italy where there’s still some sunshine because it’s up that high above the smog. And in this beautiful place, he and his daughter start cultivating animals and precious seeds in underground farms and orchards.

His end game involves luring investors with extravagant multi-course tasting menus, where the finest wines are served alongside truffle risotto and the finest Kobe beef steak, long disappeared from the rest of the world, which is surviving (barely) on a mung bean-derived protein.

“What it amounted to was skies that were gray and kitchens that were gray. You could taste it: gray. No olives, no quails, no grapes of the tart green kind … no saffron, no buffalo, no polished short-grain rice.”

So, what is a young American chef to do?

Her longing for sunshine and pistachios is so great she talks her way into the chef job for the fat cat on his mountaintop. Read more »

by David Winner

São Luís: Far Northeast of Brazil

People crowd around a samba band playing on a crumbling colonial staircase. A man in his early twenties lightly touches my shoulder as I climb upwards, whispering something in Portuguese that I don’t understand. I don’t think he’s trying to sell me anything. I stick out, a white American in a black and brown part of Brazil, but no one has been approaching me.

Smiling vaguely at him, I keep going, sipping vacantly from the huge caipirinha that I’d purchased from a street vender earlier in the evening.

Once I reach the top of the stairs, free from the crush of the crowd, I stand listening to the music, inelegantly bumping my hips in some approximation of dancing.

Ten years ago on another riotous Saturday night, I’d visited São Luís before. And found its denizens drinking, dancing, singing all over the Centro Histórico like in some MGM musical. But a fundamental change has occurred. Before, everyone had been evidently heterosexual, no one announcing their queerness in a way that a bystander could detect. But now, below the staircase and the sambistas, throughout the streets, are women coupled with women, men coupled with men, trans men, trans women, and drag queens like I’d landed in a pride parade, a queer explosion only months past Lula’s victory over the virulently homophobic Bolsonaro.

The man who’d spoken to me before appears at my side and whispers into my ears again.

The man who’d spoken to me before appears at my side and whispers into my ears again.

I smile, perhaps I say, “sim,” the universal yes of miscomprehension.

But then he speaks to me in a language that I’ve barely heard in São Luís, English.

In recent years, I’ve taken to wearing odd polo shirts that I’ve purchased on my travels, and the young man is sweetly informing me that the one I have on now is “inside out,” that very particular idiom streaming seamlessly from his mouth. Read more »

by Anton Cebalo

In the past decade, the writer Simone Weil has grown in popularity and continues to provoke conversation some 80 years after her death. She was a writer mainly preoccupied with what she called “the needs of the soul.” One of these needs, almost prophetic in its relevance today, is the capacity for attention toward the world which she likened to prayer. Another is the need to be rooted in a community and place, discussed at length in her last book On the Need for Roots written in 1943.

In the past decade, the writer Simone Weil has grown in popularity and continues to provoke conversation some 80 years after her death. She was a writer mainly preoccupied with what she called “the needs of the soul.” One of these needs, almost prophetic in its relevance today, is the capacity for attention toward the world which she likened to prayer. Another is the need to be rooted in a community and place, discussed at length in her last book On the Need for Roots written in 1943.

The question of “rootedness” was a pressing problem, particularly for the first half of the 20th century. In the preface to The Origins of Totalitarianism, philosopher Hannah Arendt noted that the two world wars had produced “homelessness on an unprecedented scale, rootlessness to an unprecedented depth.” As empires and homelands collapsed after WWI, so many were uprooted from the only worlds they had known. And their newfound superfluous condition led many of them toward “fictitious homes” in the postwar years to disastrous results. Indeed, abstract loneliness had become “an everyday experience of the ever-growing masses of our century,” wrote Arendt, which had rendered them vulnerable to totalitarianism. Uprootedness, it seemed, was partly to blame for Europe’s destruction.

Writing earlier than Arendt in 1943, Weil arrived at a similar conclusion in asserting that “rootedness” was a fundamental need of the soul. In On the Need for Roots, she begins her re-rooting of humanity by outlining a few vital ingredients that are required for healthy nourishment. Yet, the key to her idea of rootedness lies in it establishing linkages to the past and future, forming an assemblage of parts that together provide one with necessary meaning. Such relational thinking often appears in Weil’s writing, as does the Greek word “metaxy” which means an “intermediary” or an “in-between place.” Of course, roots can so often be distorted, manipulated for nefarious ends, and imagined as myth. But given that we are intrinsically social beings, the need for roots as a fundamental fact of life remains sacrosanct. Read more »

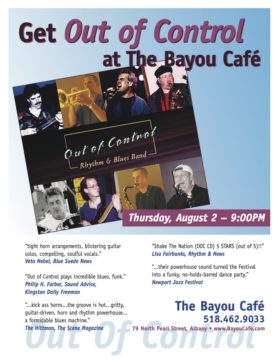

The road was generally somewhere in the Capital District of upstate New York. Think of it as a group of small cities and towns and centered on Albany, the state capital, Troy, where I lived at the time, and Schenectady, incidentally, where my grandfather had his first job in the United States, and where the band rehearsed in the basement of a photography studio in a somewhat sketchy part of town. The studio was owned by Rick Siciliano, lead vocalist and drummer for The Out of Control Rhythm and Blues Band. I played with the band from about 1985 or 86 to 1990 or so.

Not Exactly the Birth of the Blues

I am told that Siciliano started the band in the early 1980s as a means to attract women; I believe Duke Ellington was thinking the same thing when he decided to play piano. Rick got some of his buddies together to form a band. I hear he was better at attracting ladies than getting gigs. Somehow, though, he managed to gather reasonably good musicians. Chris Cernik joined on keyboards and served as den leader; he brought in his high school friend, John Eof on guitar. Then along came “Bad” Bob Maslyn on bass, Ken Drumm on alto and baritone sax to replace Rick’s buddy, Jimmy, and Rick Rourke on alto and tenor sax. There were others in and out of the band, Giles, some trumpeter whose name’s been forgotten, and then John Hines, who’d studied jazz trumpet at Berklee – that’s BerKLEE, the private music school in Boston, not BerKELEY, the flagship campus of the University of California.

They developed a repertoire organized around Blues Brothers tunes and Rick Siciliano’s taste in pop. They even had a couple of originals, “Lady DJ” (for Rick’s lust object du jour) and “Baby Tell the Truth.” Now we’re getting serious. Before you know it, Out of Control was getting gigs, but other bands were after John Hines. They put an ad in the local entertainment weekly, Metroland, looking for a substitute trumpet player.

I saw the ad, needed money, another tried and true motive for playing music. I called Ken, who acted as business manager, and set up an audition. I forget just how the audition process went, but it’s not like there were 30 trumpeters lined up to get the gig. Fact is, the time when trumpet was king was long gone by then so there weren’t many trumpeters, period. I forget just how I learned the tunes, but there were no charts. Perhaps Chris or Ken got me a set of rehearsal tapes. Whatever. I just listened and learned by ear, like all real musicians play, except for classical cats and other advanced miscreants. I soon became the one-and-only full-time trumpeter for the band. Read more »