by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Marie Snyder

It’s such a go-to now to call the enemy some version of a communist in a weird throwback to 1950s America and McCarthyism. And now the leader of the opposition accused Canada’s Prime Minister of being a Marxist, and he said it like it’s a bad thing!

It’s such a go-to now to call the enemy some version of a communist in a weird throwback to 1950s America and McCarthyism. And now the leader of the opposition accused Canada’s Prime Minister of being a Marxist, and he said it like it’s a bad thing!Lisa B0923 5 minute Tiktok explains why Trudeau is decidedly not Marxist:

“This is what Marxists believe: ‘Marxism analyses the impact of the ruling class on the laborers, leading to uneven distribution of wealth and privileges in the society. It stimulates the workers to protest the injustice.‘ Now I guess compared to the current CPC the liberals may look Marxist because the current CPC is so far right, like, you can’t even see them in the distance.”

But let’s dive a little deeper into what Marx said to see that philosophically, communists and capitalists aren’t that far apart, but both are nowhere near the neolibertarian capitalists. Kinda like Lisa said above, neoliberals are just so far to the right that everyone looks like a commie from their vantage point.

What I think is interesting is that one of the fathers of capitalism, John Locke, and one of the fathers of communism, Karl Marx, were reacting to their different situations in very similar ways. Read more »

by Rafaël Newman

All will unite—no sooner had our world

Combusted (see “The Big Bang”) than it sought

Accretion of the bits that had been hurled

To every corner (where there once was naught,

One nanosecond previous, un-warmed

By ours or any other burning stars,

Un-lit by lunar satellite), and formed,

In steady labour, suns and planets, Mars,

And Jupiter, and Venus, and the rest:

Great gatherings of what was late alone,

But now into a merry round compress’d

Was through our skies in conjunct chorus thrown.

And so it is with us, made of those bits

As well, and yearning for return to what

We once were, unities before the blitz:

One rounded whole, harmonic and uncut

As yet by gods invidious, those same

Whom we’ve appeased in solemn ritual,

With sacrifice, and planetary name,

And ceremonies individual. Read more »

I have been thinking about the culture of AI existential risk (AI Doom) for some time now. I have already written about it as a cult phenomenon, nor am I the only one. But I that’s rather thin. While I still believe it to be true, it explains nothing. It’s just a matter of slapping on a label and letting it go at that.

While I am still unable to explain the phenomenon – culture and society are enormously complex: Just what would it take to explain AI Doom culture? – I now believe that “counter culture” is a much more accurate label than “cult.” In using that label I am deliberately evoking the counter culture of the 1960s and 1970s: LSD, Timothy Leary, rock and roll (The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, The Jefferson Airplane, The Grateful Dead, and on and on), happenings and be-ins, bell bottoms and love beads, the Maharishi, patchouli, communes…all of it, the whole glorious, confused gaggle of humanity. I was an eager observer and fellow traveler. While I did tune in and turn on, I never dropped out. I became a ronin scholar with broad interests in the human mind and culture.

I suppose that “Rationalist” is the closest thing this community has as a name for itself. Where psychedelic experience was at the heart of the old counter culture, Bayesian reasoning seems to be at the heart of this counter culture. Where the old counter culture dreamed of a coming Aquarian Age of peace, love, and happiness, this one fears the destruction of humanity by a super-intelligent AI and seeks to prevent it by figuring out how to align AIs with human values.

I’ll leave Bayesian reasoning to others. I’m interested in AI Doom. But to begin understanding that we must investigate what a post-structuralist culture critic would call the discourse or perhaps the ideology of intelligence. To that end I begin with a look at Adrian Monk, a fictional detective who exemplifies a certain trope through which our culture struggles with extreme brilliance. Then I take up the emergence of intelligence testing in the late 19th century and the reification of intelligence in a number, one’s IQ. In the middle of the 20th century the discourse of intelligence moved to the quest for artificial intelligence. With that we are at last ready to think about artificial x-risk (as it is called, “x” for “existential”).

This is going to take a while. Pull up a comfortable chair, turn on a reading light, perhaps get a plate of nachos and some tea, or scotch – heck, maybe roll a joint, it’s legal these days, at least in some places – and read.

by R. Passov

In 2010, the company for which I was then Treasurer was invited to send me to China. The purpose of the trip was to meet with senior members of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) as well as the Shanghai stock exchange as a prelude to becoming the first US company to issue bonds to be traded on the Shanghai exchange.

Before discovering that there were numerous companies in line to be ‘first’ I met with a senior official of the NDRC. Along with my travel companion, a Chinese national who had relocated to New Jersey and worked on my team, I arrived at a palatial office exactly at the right time, only to wait perhaps as along as 45 minutes, maybe longer.

Eventually my companion and I were escorted into a cavernous conference room, in the center of which was an impossibly long table surrounded by as many as 40 high-backed, elaborately upholstered chairs. We were instructed to take seats away from the table against a far wall. After more waiting, a senior official entered the room followed by two assistants and proceeded to a chair at the very center of the table.

After the official was comfortably seated we were instructed by his assistants to move to the table and occupy the two seats directly across. One of the assistants left and our host began the meeting.

Introductions were short. The NDRC official knew who we were, and perhaps a lot more. I only knew that he was a Vice Chairman and according to my colleague ‘very, very senior.’ The Vice Chairman was politely condescending and direct: When, he wanted to know, would my company be able to commit to a securities offering. Read more »

by Bill Murray

This month’s travel column includes suspiciously little travel – just two short walks, to a courthouse and a jailhouse. I live in Atlanta, where quite a bit of national politics has happened in those two buildings these last few weeks.

I walked downtown a couple of weeks ago when things were going on down there that you wouldn’t call festive, August is too hot for festive, but they were purposeful, and expectations ran high. Peoples’ opinions diverge, don’t they, but until the Trump indictments were actually handed up August 14, everybody at least agreed something important was coming and that it would shape events.

To walk from my part of town, Atlanta’s big busy Midtown, to the sprawling government complex downtown, is to walk “right down Peachtree,” as much loved Atlanta Braves baseball announcer Ernie Johnson used to say when describing a pitch right down the middle.

From Midtown you walk Atlanta’s main street a couple of miles south. There’s a dodgy block or two and then a positively anti-human overpass where noise, grit and gridlock coalesce over a squeezed together forced marriage between interstates 75 and 85. We call that the Downtown Connector.

Once that’s over you forge alongside Woodruff Park (for sixty years Robert W. Woodruff personified Coca-Cola); you are now in the heart of downtown, and continue beyond an iconic neon Coca-Cola sign and through the disused entrance to what has been, on and off again, Underground Atlanta.

After that barriers were up, roads were shut and cadres of traffic cops moved about. TV trucks staked out the Lewis R. Slayton Courthouse for a couple of weeks down there and everybody with a supporting role in presenting the Donald Trump drama, TV techs, cops, drivers, caterers, couriers and a few protesters deserved hazardous duty pay for managing in the 100 degree-plus daily heat.

Out here in the provinces these felt like important events; it seemed like purposeful people were busy with weighty affairs, even if it was only all in the service of getting one man and his associates in trouble with the law. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

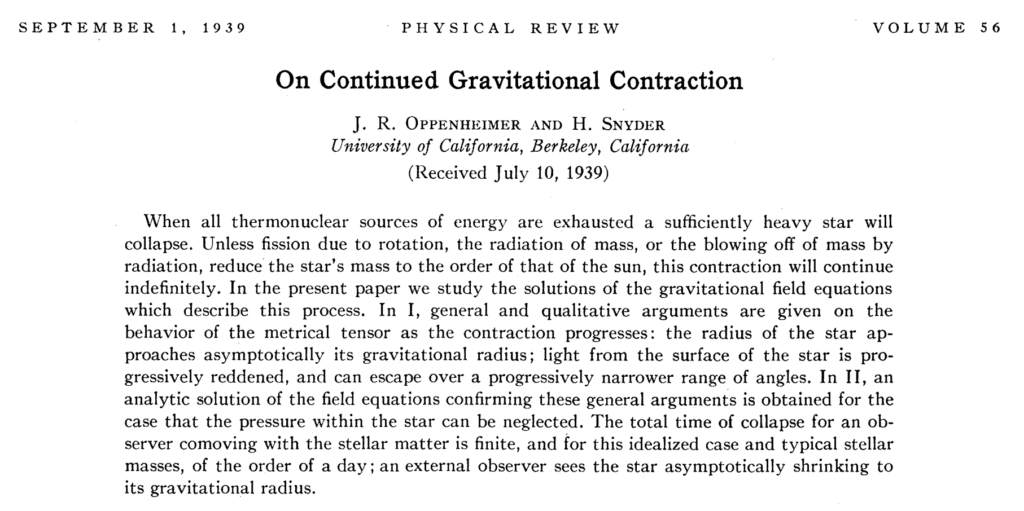

Scientific ideas can have a life of their own. They can be forgotten, lauded or reworked into something very different from their creators’ original expectations. Personalities and peccadilloes and the unexpected, buffeting currents of history can take scientific discoveries in very unpredictable directions. One very telling example of this is provided by a paper that appeared in the September 1, 1939 issue of the “Physical Review”, the leading American journal of physics.

The paper had been published by J. Robert Oppenheimer and his student, Hartland Snyder, at the University of California at Berkeley. Oppenheimer was then a 35-year-old professor and had been teaching at Berkeley for ten years. He was widely respected in the world of physics for his brilliant mind and remarkable breadth of interests ranging from left-wing politics to Sanskrit. He had already made important contributions to nuclear and particle physics. Over the years Oppenheimer had collected around him a coterie of talented students. Hartland Snyder was regarded as the best mathematician of the group.

Oppenheimer and Snyder’s paper was titled “On Continued Gravitational Contraction”. It tackled the question of what happens when a star runs out of the material whose nuclear reactions make it shine. It postulated a bizarre, wondrous, wholly new object in the universe that must be created when massive stars die. Today we know that object as a black hole. Oppenheimer and Snyder’s paper was the first to postulate it (although an Indian physicist named Bishveshwar Datt had tackled a similar case before without explicitly considering a black hole). The paper is now regarded as one of the seminal papers of 20th century physics.

But when it was published, it sank like a stone. Read more »

by Jerry Cayford

The topic today is misinformation and knowledge, conspiracy theory and evidence, not biblical exegesis. When Saint Paul tells the Corinthians, “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face” (1 Corinthians 13:12), he is contrasting partial, human knowing with the perfect knowing that will come when we reunite with God. He is not dissing human knowledge, and yet one detects an unmistakable yearning for that better sort of knowledge.

These two kinds of knowledge express two different philosophical theories of truth. When the Scientific Revolution came along some sixteen hundred years after Paul wrote, people had had enough of this “through a glass darkly” stuff and decided it was time to move on to seeing reality “face to face.” That moving on, though, never quite left the dark mirrors behind, and we are living today through an acute conflict between these theories.

Today, we are at another moment of historic transition, with the atomic bomb behind us and artificial intelligence ahead. In writing about our moment, I will do a bit of philosophy and some intellectual history—about as quick and dirty as you saw in the previous paragraph—through the lens of three pieces by New York Times columnists (you don’t need to read them). All three discuss conspiracy theories and how to confront them. We will find our two competing theories of truth between the lines. Seeing them in action can illuminate our moment, and maybe the path ahead.

The first column, by Farhad Manjoo, explains why it is pointless or even counterproductive to argue with conspiracy theorists like Robert Kennedy Jr. The rebuttal to Manjoo by Ross Douthat explains that the alternatives to arguing are far worse. The third, by Paul Krugman, explains how to argue. I think the three together are instructive about how we can know things, even when we never confront reality face to face but see everything through a glass, darkly. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Shredder Self-portrait, NYC, August 2023.

Sughra Raza. Shredder Self-portrait, NYC, August 2023.

Digital photograph.

by Lydia Stryk

Riding the train to the small city of Darmstadt to sleep over with a friend after a day spent at the Frankfurt Book Fair, I observed an impeccably dressed elderly gentleman sitting several rows away from me across the aisle.

He wore an elegant calf-length overcoat which men of a certain class in Germany are partial to wearing. His shoes were fine leather and shining. He was tall, with excellent posture, a full mane of white hair and the bluest of eyes, which I noted because they reminded me of my father’s eyes and because they were staring into the beyond behind me. He was in possession of a large expensive-looking wrist watch to which he turned his attention occasionally. And though I could see no evidence of a briefcase, his would have been top of the line.

He had, in fact, the air of a publisher of tasteful literary titles on his way home from a successful but tiring day at the fair. And I pictured him the sort who would have attended the fair every year without exception until the pandemic temporarily shut it down and would continue to attend, out of habit, for as long as he was able. Perhaps, he was the scion of a publishing empire, I told myself, a fitting story.

It had been a long day, and I was happy to be on the train. Nothing else about the day had been happy, so eventually my mind wandered away from the old man to my own state of affairs. I was cold and hungry and admittedly forlorn, none of this conducive to conjecture and true curiosity. I closed my eyes.

And that is when a certain commotion broke out on the until-that-moment quiet and peaceable train. Concerned women’s voices could be heard, and I opened my eyes to find the concern centered around the elegant elderly man. My station was approaching and though readying to disembark, I was able to make out the following: The elderly gentleman had apparently turned to his seat companion and asked her where the train was heading and if she could tell him where he was. Upon questioning, it became clear that he did not know where he wanted to go. The literary lion of my imagination had presumably boarded a train with no direction or purpose and was lost. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Tim Sommers

Back in June, Dr. Peter J. Hotez, an expert on neglected tropical diseases and vaccines, made a splash when he categorically refused to participate in a public debate on vaccines with vaccine-denier Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. on Joe Rogan’s podcast.

Dr. Hotez had been on Rogan’s show before, more than once, and said he would go on again – but not to debate. Among those “urging” him (to put it politely) to do so were Rogan (who offered him $100,000 dollars), Elon Musk (the richest man in the world) who said that Dr. Hotez is “afraid of a public debate because he knows he’s wrong,” a social media mob of thousands, and finally a pair of stalkers arrested outside his home.

Why didn’t Dr. Hotez just do the debate? I don’t know. But I think it’s because he knows that experts should not participate in public debates against nonexperts.

Maybe, I should mention why I feel qualified to address this topic. I participated in competitive academic and public debates, of various sorts, as a debater, a judge, and a coach for ten years. I have used debate to teach philosophy courses, and have written four academic papers on how to make academic debate more relevant to teaching and scholarship.

So, here we go. Top ten reasons experts should not debate nonexperts in public debates. Read more »

by Joseph Carter Milholland

In my last column, I wrote about the interconnectedness of the literary canon. My argument was that canonical books are best read in the context of other canonical books – that we only fully appreciate a great work of literature when we also appreciate the other great works it is inextricably bound to – both the books that influenced it, and the books it influenced.

I will admit that this argument can lead one astray: if applied improperly, we lose sight of individual authors and individual works, and only focus on the narrative of literary history. Worse yet, we will arbitrarily force certain books to conform to our expectations of the canon, instead of reading them on their own terms. I do not think that there is anything in what I proposed that would necessarily lead to this kind of reading, but it is a very easy mistake to make (and one I will confess to having made in the past). To avoid making this mistake, I will now propose a complementary method for reading the canon: to seek out and understand the difference between what I call the “mainstream” and the “marginal.”

I am using the terms mainstream and the marginal to denote two types of literary artistry. Whenever we read a great book, there is a wide spectrum of ways in which we enjoy it: on the right end of this spectrum, we have the kinds of enjoyment that we can find in almost every great book, no matter where or when it was written; in the center is the ways in which the book reflects the finest features of a specific genre or literary tradition; and on the far left is the way in which that particular book gives us its own unique pleasures. The literary artistry that falls in the right hand end of this spectrum I call the mainstream, and the artistry on the left hand side I call the marginal. I realize this definition is abstract and somewhat cumbersome, so throughout this essay I will supply examples that I think better illuminate what I am getting at. My first example: the catharsis we experience at the end of great tragedy is an example of mainstream artistry; the caesura in Anglo-Saxon verse is an example of marginal artistry.

Some more clarifications are in order. Read more »

by Steve Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

Harry Frankfurt, who died of congestive heart failure this July, was a rare academic philosopher whose work managed to shape popular discourse. During the Trump years, his explication of bullshit became a much used lens through which to view Trump’s post-truth political rhetoric, eventually becoming deeply associated with liberal politics.

Harry Frankfurt, who died of congestive heart failure this July, was a rare academic philosopher whose work managed to shape popular discourse. During the Trump years, his explication of bullshit became a much used lens through which to view Trump’s post-truth political rhetoric, eventually becoming deeply associated with liberal politics.

Ironically, the original target of Frankfurt’s argument was an earlier “post-truth” movement: postmodernism, which became the heart of liberal political correctness in the 1980s and 1990s. Interestingly, that shift from a liberal to a conservative target illustrates the way in which postmodern machinery has infiltrated politics.

On “On Bullshit”

Frankfurt had an illustrious career as a philosopher, but his immortality rests on a cute and clever argument he published in his most famous piece, “On Bullshit.” In it, Frankfurt distinguishes between lying and bullshitting. Liars intentionally deceive, believing they know the truth and working to keep ownership of it to themselves. Bullshitters, on the other hand, are perfectly happy to convey the truth… as long as doing so serves their pragmatic rhetorical goals. Bullshitters want you to believe something and are comfortable using either truth OR lies to shape your views. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

Aesthetic properties in art works are peculiar. They appear to be based on objective features of an object. Yet, we typically use the way a work of art makes us feel to identify the aesthetic properties that characterize it. However, dispassionate observer cases show that even when the feelings are absent, the aesthetic properties can still be recognized as such. Feelings seem both necessary yet unnecessary for appreciation of the work.

Aesthetic properties in art works are peculiar. They appear to be based on objective features of an object. Yet, we typically use the way a work of art makes us feel to identify the aesthetic properties that characterize it. However, dispassionate observer cases show that even when the feelings are absent, the aesthetic properties can still be recognized as such. Feelings seem both necessary yet unnecessary for appreciation of the work.

How do we square this circle?

When we ascribe to works of art properties such as beautiful, melancholy, mesmerizing, charming, ugly, awe-inspiring, magnificent, drab, or dynamic we are typically reporting how the work affects us, and we often use what we loosely call “feelings” to help in the ascription. A painting is charming if the viewer feels charmed. The architecture of a building is awe-inspiring if an admirer has the feeling of being awed. To say that a musical passage is beautiful but it leaves me uninspired and bored is peculiar and would require some special explanation for what is meant by “beautiful” in this case. We typically use the degree and kind of pleasure we feel about an object to be one measure of its beauty. The feelings involved in our response to artworks or other aesthetic objects need not be full blown emotions. As many commentators have pointed out, a sad song does not necessarily make one feel sad if you have nothing to be sad about. In fact, we often find sad songs exhilarating. Yet sad songs make us feel an analog to sadness which helps us attribute the property “sad” to the song.

In other words, there is something that it is like to feel charmed, awed, in the presence of beauty, or “sad-adjacent” that typically accompanies the identification of that property in an object. And the feeling state helps us identify the property. We know a film is amusing because it makes us feel amused, joyful because it sparks feelings of joy, etc.

But this raises a puzzle about dispassionate observers. Read more »

by Richard Farr

Early in life, when a child’s tender ear is suppos ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say it’s only a game.

ed to be protected from blasphemy, I must have overheard someone say it’s only a game.

I went to the kind of English boarding school at which rugby, patriotism and Christianity were serious business, competed with each other for our attention, and sometimes threatened to blur. You sensed that on any damp Wednesday afternoon, just before we hoofed it down to the games fields, a gowned Master might seek to ramp up our enthusiasm by reminding us of Jesus Christ’s game-winning try against the Zulus at Rorke’s Drift. Or that on Sunday the chaplain in his pulpit (we were High Church Anglican, very smells and bells) might decide to hold forth interminably on the significance of the Archangel Gabriel’s surprise appearance in the changing rooms after that excellent match against the Germans at El Alamein.

Whether in chapel or on the sideline it was all about unity, the team, the sense of heartfelt belonging. That was what mattered. And I’m not complaining. OK, I am complaining, because I hated it. But perhaps that really is a good way to socialize adolescent boys. Certainly most of them seemed to take to it like ducks or pigs to their proverbial substances. But I knew early on that I didn’t want the team, or respect it, or feel that I belonged. Unluckily for me, or perhaps not, the more they insisted the more alienated I felt from the whole scheme. Luckily for me, there were other heroic misfits. Read more »

by Deanna Kreisel [Doctor Waffle Blog]

The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.

The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.

It had all started innocently enough: the two of them had decided to take their dogs C. and Z.[1] on a late-night stroll through M.’s neighborhood, which happens to contain a large antebellum estate known as Rowan Oak. For the benefit of the 99.999% of this publication’s readers who do not live in Oxford, Mississippi: this particular large antebellum estate was home to William Faulkner from 1930 to the time of his death. For the benefit of the 0.001% of this publication’s readers who do not know who that is: William Faulkner was one of the greatest American novelists of the twentieth century, an early practitioner of the subgenre that came to be known as “Southern Gothic,” and a lifelong resident of Oxford who wrote about the town and surrounding area (fictionalized as “Yoknapatawpha County”) in 16 novels and over 50 short stories.

So M. and P. were strolling the other night with her tiny adorable dog and his larger adorable dog, enjoying the delicious bosky springtime air, when they made the fateful decision to extend their walk to the grounds of Faulkner’s estate. They were chatting away when they passed the invisible property line, at which point they were immediately assaulted by a brilliant search light splitting the darkness. A disembodied voice—they couldn’t see the speaker, since he hovered in the dark behind the light—demanded to know what they were doing on the grounds of the estate, which was closed for the night. [N.B. there was no Hours of Operation indication at the time, although a brand-new sign has since mysteriously appeared right on that spot.] M. and P. apologized profusely and were backing away from the bright light in their eyes when the voice went on: “You know, there are a lot of good reasons not to walk around this place at night. I mean … I’ve heard stories.”

P. was pretty sure he wanted to get out of there immediately, but M. was now intrigued. “Oh? Like what?” Read more »