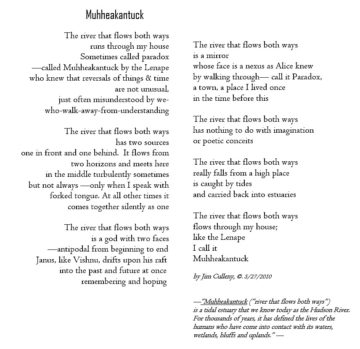

—Two poems separated by 5 years have come together

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

—Two poems separated by 5 years have come together

by Steve Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

French philosopher and sociologist Auguste Comte argued that there ought to be an atheist’s religion, the Religion of Man, with holidays, rituals, symbols, saints, and social gatherings for those who maintain a scientific worldview without belief in an all-being. If such a religion existed, 2023 would be a celebratory year: the centenary of its version of the Council of Nicea, the conference at Erlangen.

The First Council of Nicea, in 325 C.E., brought together bishops from across the Christian world. At the time, there was no single institutional structure and no coherent theology within Christianity. Bishops and theologians held a wide range of positions and endorsed quite different practices, which resulted in a splintering within the Christian community. One question about which there was disagreement: is Jesus God or the son of God? If Jesus isn’t God, then aren’t Christians violating the first commandment not to put other gods before God? If Jesus is God, then how can one be the son of the other? The ensuing debate led to the doctrine of the Trinity coming out of Nicea.

The First Council of Nicea was instigated by the Emperor Constantine, who was understandably fond of strong institutions wielding power. He brought the various players together to hash out their differences and create a unified Church, which then became the dominant power not only in religious life, but in geopolitical matters as well.

A similar impulse guided German advocates of what they termed “the scientific philosophy” in the early decades of the 20th century. Chief among them was philosopher Hans Reichenbach. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Hope.

Digital photograph, July 2020.

by Claire Chambers

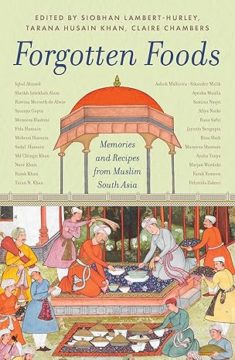

I’m excited about the imminent Halloween publication date of Forgotten Foods: Memories and Recipes from Muslim South Asia, a book I edited with Siobhan Lambert-Hurley and Tarana Husain Khan. The new book is a partner volume to Desi Delicacies which I edited and wrote about for this blog in 2021.

I’m excited about the imminent Halloween publication date of Forgotten Foods: Memories and Recipes from Muslim South Asia, a book I edited with Siobhan Lambert-Hurley and Tarana Husain Khan. The new book is a partner volume to Desi Delicacies which I edited and wrote about for this blog in 2021.

One of the most nourishing things about venturing into cookbooks, food writing, and editing heritage recipes has been getting to know a whole new world of South Asian literature. As part of this, I was delighted to be sent Nilosree Biswas’s sumptuous book Calcutta on Your Plate, with its beautiful food photography by Irfan Nabi. Desi Delicacies had included two chapters, one a short story and the other an essay, by Bangladeshi writers. Now Forgotten Foods contains an essay entitled ‘Islam on the Table in [West] Bengal’, in which Jayanta Sengupta especially zeroes in on the Calcutta mutton biryani, complete with its distinctive inclusion of potatoes. However, I didn’t know too much about Bengali cuisine beyond what I had learnt from these pieces, as well as being familiar with British-Bangladeshi curry houses and the eastern South Asian region’s reputation for a sweet tooth. Read more »

South Asian literature. As part of this, I was delighted to be sent Nilosree Biswas’s sumptuous book Calcutta on Your Plate, with its beautiful food photography by Irfan Nabi. Desi Delicacies had included two chapters, one a short story and the other an essay, by Bangladeshi writers. Now Forgotten Foods contains an essay entitled ‘Islam on the Table in [West] Bengal’, in which Jayanta Sengupta especially zeroes in on the Calcutta mutton biryani, complete with its distinctive inclusion of potatoes. However, I didn’t know too much about Bengali cuisine beyond what I had learnt from these pieces, as well as being familiar with British-Bangladeshi curry houses and the eastern South Asian region’s reputation for a sweet tooth. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Jerry Cayford

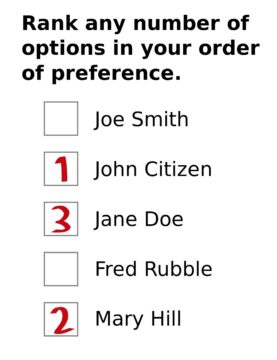

We think we live in a democracy, though an imperfect one. Every election, our frustrations bubble up in a list of proposed reforms to make our democracy a little more perfect. Usually, changing the Electoral College heads the list, followed by gerrymandering and a motley of campaign finance, voter suppression, vote count integrity, the dominance of swing states, etc. My own frustration is the very banality of this list, its low-energy appearance of arcane, minor, and futile wishes, like dispirited longshot candidates carpooling to Iowa barbecues. Enormous differences among these reforms are masked by the generic label, “electoral reform.”

One change—Instant Runoff Voting—should stand alone, for it’s far more important than the others, or even than all of them put together. Democracy is supposed to keep government and voter interests aligned, with elections correcting the government’s course; without runoffs, though, that alignment is elusory because no electoral mechanism really tethers the government to the public interest. Where other flaws in our electoral process have in-built, practical limits on the damage they can do, elections that lack runoffs have no limit on the divergence they allow between leaders and citizens. Which may explain a lot about where we are today.

Many years ago, during the Cold War, I worked for a military policy research company. I had an epiphany there: foreign policy was heavily influenced by the fact that two-player, zero-sum games are easy to analyze. If everything that’s good for the Soviet Union is equally bad for the United States, and vice versa, and no other players matter, it’s easy to settle on a logical action in any situation. Today’s polarized, cutthroat domestic politics is eerily reminiscent of those Cold War foreign policy days. First-past-the-post elections—the kind we mostly have in the U.S., where whoever gets the most votes wins, with or without a majority—produce two parties with perfectly opposed interests and easy “for us or against us” answers. Everyone is familiar with the electoral logic that drives this result: the logic of “spoilers.” The further consequences of spoiler logic, though, are much less familiar. Read more »

by Nils Peterson

Auden says somewhere that a woman should be wary if her sweetheart starts sending her love poems because, for the duration of the writing, she wasn’t being thought of, the poem was.

Auden is being sly-spirited here, though there is truth in what he’s saying. The love poet is paying attention to his or her feelings about the beloved, what is being called up out of the inner life. These feelings are brought on by the loved one, but they are uniquely one’s own. You’ll remember that in the scene when Benedick realizes he is in love with Beatrice his last words are, “I’ll go and get her picture.” This was not to memorize the mole on her upper lip, her dimple, or pretty chin, but to be in her continual presence so that he can explore the feelings she evokes. All lovers, in their amazement ask, What is going on with me? What do I feel? What do I want?

When I see you

even for a moment

I cannot speak

my tongue is broken

fire rides under my skin

I am blind, my ears ring,

and I sweat and tremble

with my whole body (Sappho, trans. Peterson)

Wild Nights – Wild Nights

Were I with thee

Wild nights should be

our luxury! (Emily Dickinson)

I would like to watch you sleeping,

which may not happen.

I would like to watch you,

sleeping. I would like to sleep

with you…. (Margaret Atwood, “Variations on the Word, Sleep”)

Why am I different? What has happened to me? What am I hearing when I hear her speak my formerly ordinary name? Read more »

by Paul Braterman

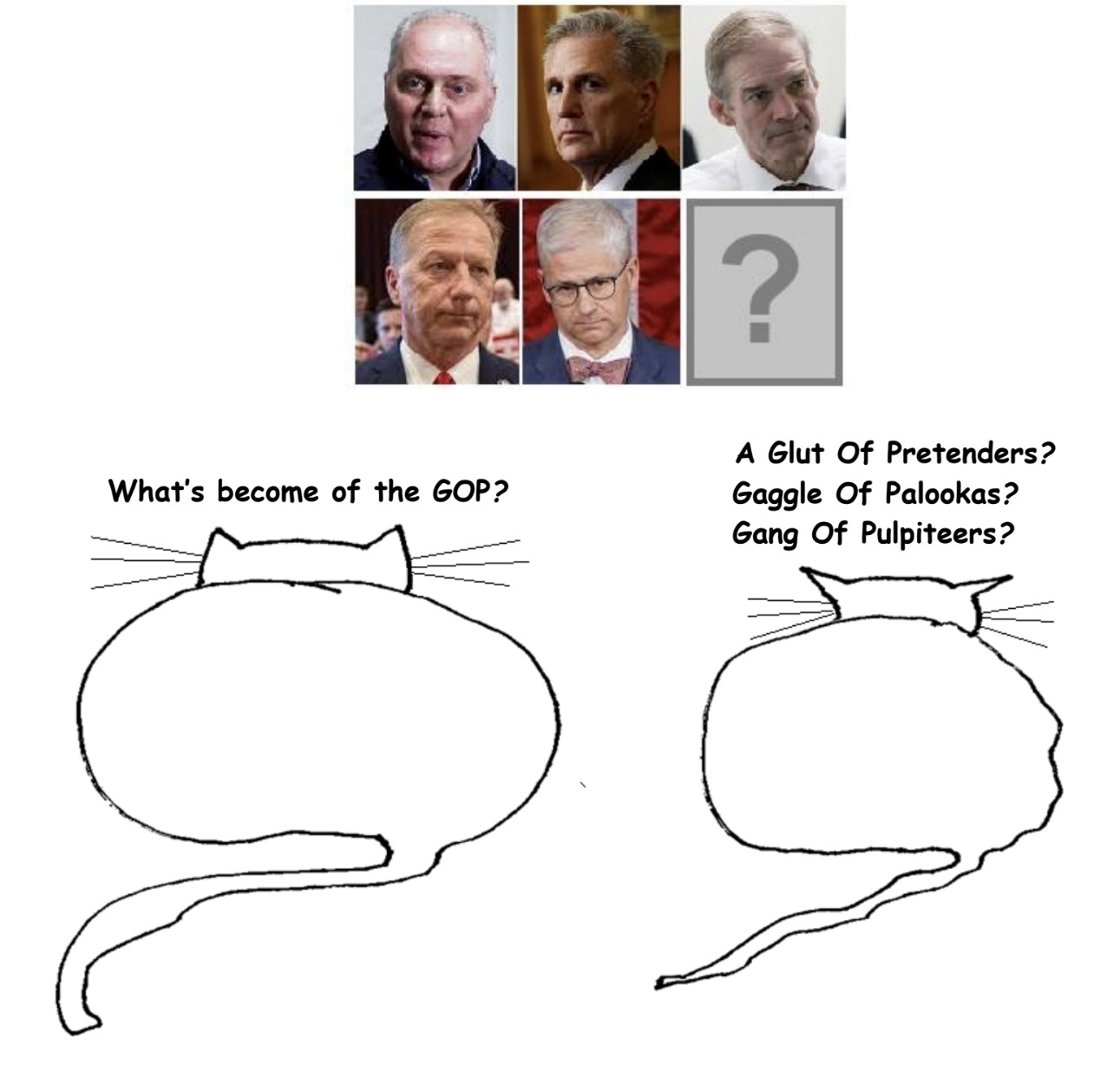

By now you will know that the new Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Mike Johnson (Louisiana 4th District) was among those who voted against accepting the results of the 2020 Presidential election. You may also know that he is opposed to the concept of same sex marriage, which in some way he regards as undermining individual religious freedom, and wants to pass a law making abortion illegal throughout the US. You probably also know that he has denied that human activity is a cause of global warming, and has accepted more campaign funds from the fossil fuel industry than from any other source. There is a high chance that you have heard him share Marjorie Taylor Greene’s view that the problem in mass shootings isn’t guns, it’s the human heart (Guns don’t kill people. Human hearts kill people.) What you may not know are his views on the causes of the moral decline that, like authoritarian pulpiteers throughout the ages, he sees happening all around him. He has, however, stated those views very plainly, at a presentation he gave in Louisiana in 2016, available here. [Edit: This, like many of his pre-Speakership YouTube presentations, is no longer publicly available.] I have read the transcript of this, suffering so that you don’t have to, and despite many decades of following the utterances of people who share his views I was surprised by what I found.

Here he is, speaking at a less than overcrowded Shreveport Christian Centre, which describes itself as mandated “to participate with the Lord in establishing His kingdom in all areas of our culture. We desire to use the authority given to us to promote and participate in seeing the Lord’s purposes rule in the church, business, media, arts, education, government and family arenas.” The authority, of course, is given by God. He is standing at the front of a platform, and behind him are musical instruments and two flags. The flag of the United States, and the flag of Israel. The Israeli Right has been wooing the American Religious Right for decades, and the unquestioning support of the American Religious Right has done much to make Israel what it is today.

Here’s part of what he said; you can find the full text on the link. My account is rather rambling, although nowhere near as rambling as the original material, and I will quite understand if you just want to skip to the key points at the end. Read more »

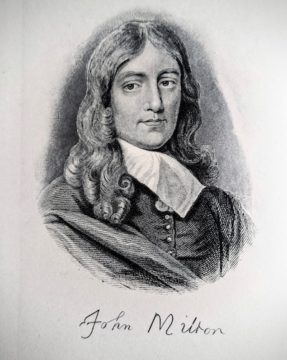

by Richard Farr

We called my English teacher Scab for no particular reason except that it took the edge off our terror. A big man in a double breasted jacket, he wore tinted glasses that hid his expression. His head looked as if it had been carved rather carelessly from a boiled ham. “You are not going to like me,” he said to us in our first class, when I was 13. “I am the iron fist inside this institution’s velvet glove.”

It was a front, mainly. He did not suffer fools, including his pupils and most of his colleagues, at all gladly. He probably dreamed of teaching at a university, where he could have discussed Chaucer’s prosody without first getting people to stop making farting noises.

By the time I turned 17 he had softened a little, as if he could see that some of us might one day turn into bona fide human beings. And that year the national syllabus gods gifted us what was (as I gradually came to see) an absolute corker. Among other succulent morsels there were chunks of The Canterbury Tales, all of both Othello and Lear, Gulliver’s Travels, Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings, Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party.

The most intimidating item by far was Paradise Lost Books IX and X — a hundred-score lines of theology that we found impenetrable, as if we were trying to hack our way back into an overgrown Eden long after its attendants’ banishment. Our feet tangled in the archaic vocabulary. Classical allusions stung our ignorant faces at every turn. (“Of Turnus for Lavinia disespous’d”? “Not sedulous to indite”? Both of these gems were on the first page of Book IX.) Scab spent a couple of weeks trying to make sense of it all for us but we were illiterate adolescents, lost and flailing inside an erudite adult’s poem. One day he sighed melodramatically and changed tactics. “I’ll read it to you,” he said. “Don’t think. Don’t even try to think. Just listen.”

The most intimidating item by far was Paradise Lost Books IX and X — a hundred-score lines of theology that we found impenetrable, as if we were trying to hack our way back into an overgrown Eden long after its attendants’ banishment. Our feet tangled in the archaic vocabulary. Classical allusions stung our ignorant faces at every turn. (“Of Turnus for Lavinia disespous’d”? “Not sedulous to indite”? Both of these gems were on the first page of Book IX.) Scab spent a couple of weeks trying to make sense of it all for us but we were illiterate adolescents, lost and flailing inside an erudite adult’s poem. One day he sighed melodramatically and changed tactics. “I’ll read it to you,” he said. “Don’t think. Don’t even try to think. Just listen.”

What happened next I can’t articulate with any clarity, except to say that the words melted onto his tongue like expensive chocolates, rendering his voice thick and smooth, and it was as if he had become Milton; it was as if I was present at the creation and was witnessing the poem erupt for the first time from the dark materials of the blind freedom-fighter’s imagination.

“Don’t think. Just listen.” Read more »

by Mark Harvey

A week before he died, I drove my good friend and ranch foreman, Rey Rodriguez, to Denver to catch a bus to Chihuahua, Mexico. He was taking a two-week vacation to visit his family there. On the three-hour drive to Denver, we practiced answering questions for the test given to immigrants applying for US citizenship. He had downloaded 100 potential questions onto his phone and had been studying for more than a year to take the test. I often wondered why he didn’t take the test sooner because he had the questions down. Most of the test is composed of the sort of useless memorization you’d find in an American high school in 1950.

Who was Benjamin Franklin? What do the fifty stars on the American flag represent? Where is the Statue of Liberty? Who wrote the Declaration of Independence?

I have no idea how this test ensures that an immigrant will make a good citizen other than ensuring that the applicant knows far more about American history than the complacent homeowner in Pasadena, California, going all red-faced about keeping “illegals” out of ‘America—between bites of avocado that the “illegals” planted, picked, and packed.

We probably went through 60 questions and Rey didn’t miss one. My suspicion is that Rey had very mixed feelings about becoming an official gringo. Like many Mexicans, he had done the Mexico-America dance for years. Traveling great distances from Chihuahua to places like Yuma, Colorado, to work on a giant feedlot, the Central Valley of California to harvest vegetables, or western Colorado to work on our ranch.

He liked America okay and admired certain things about gringos. But his heart and soul were in Mexico. America was a way to stay afloat financially. I asked him what the average wage of a ranch worker in Mexico was and I reckon American ranch workers make in the neighborhood of 10 times as much. Read more »

by Deanna Kreisel (Doctor Waffle Blog)

I am no stranger to waking up in the middle of the night with a nameless feeling of dread. Like everyone else I know, I developed chronic insomnia around age 40, which was exacerbated by the “election” of Trump and the ongoing pillage of American democracy. And then perimenopause wreaked its havoc in the form of hormonal swings, night sweats, and troubled dreams. But this was different. This night—just over a month ago—I woke bolt upright out of a dead sleep, gasping for air, disoriented and terrified. I leapt out of bed and staggered to the bathroom, so dizzy I was bumping into walls. I found the toilet, closed the lid (an ongoing bone of contention in our household), and sank down with my head between my knees. I was dying. I knew, absolutely and with pure and stainless conviction, that I was dying. Dizziness washed over me, an intense feeling of disorientation, and I knew that it was my spirit separating from my body. I was swept with waves of grief. I haven’t written everything I want to write. My partner is in the next room and I don’t want to say goodbye yet. My family, my friends. Work to do, parties to throw. This toilet—it really needs to be cleaned. This is not dignified. I promise, Powers That Be, that from this moment forward I will no longer be cavalier about my life, if you just spare me now.

Suddenly a scrap of memory. A conviction that one is dying—that sounds familiar. I think … that can happen in panic attacks? Maybe I’m having a panic attack? But—how can this be? I have had panic disorder and intermittent generalized anxiety since I was 16, and have had hundreds of panic attacks in my life—never before did I become convinced that I was dying. For me the worst part of panic is the feeling of derealization, as if the world around me is fake and I am in a dream. (It’s very difficult to explain why this feeling is so horrifying to those who have never experienced it—you just have to trust me.) But that night in the bathroom I suddenly remembered that the sensation of dying is on the long list of panic attack symptoms, one I had always skipped over when reading about my disorder since it didn’t apply to me. And yet here we were.

Okay, okay. I might as well try the usual techniques I’ve perfected over the years. Deep breathing. Walking in circles while shaking my hands and feet. Splashing cold water on my face. Above all—not fighting it. Letting the feelings pass through me and trusting that I would come out the other side. It worked; I was released from the iron grip of terror; my soul returned to my body; I lived.

I did not sleep again that night. Read more »

by Mike Bendzela

An Ape meets a Holy Man who is visiting a zoo. The Holy Man has made a career of debasing such animals as the Ape, and now the Ape sees an opportunity to preempt him. She is a fabulist and must act quickly.

“The animals are trying to tell you something.”

“I don’t speak animal,” the Holy Man sneers.

The Ape ignores him and continues: “Once upon a time–”

Some monitor lizards–opposed to the increasing presence of cobras in their midst–held a public meeting to air their concerns. “Fellow Lizards!” one outspoken lizard said to those gathered. “The cobras intend to surround us, defeat us, and take our land. But they won’t stop there; we all know how snakes are. If we don’t do something quickly, they will swallow all our young!” Inflamed by this speech, the lizards quickly mobilized. They sought out the snakes, surrounded them, and defeated them. But, for reasons no one has been able to fathom, the triumphant lizards then devoured every snake egg they could find.

“Indeed,” the Holy Man says, “someone is always plotting against you.”

“Would you like to hear the moral?”

“I’m all ears.”

The most depraved acts may be committed in the name of preventing depravity.

“In other words,” the Holy Man says, “you can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs.” Read more »

by David J. Lobina

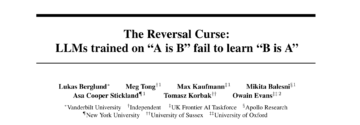

Artificial General Intelligence, however this concept is to be defined exactly, is upon us, say two prominent AI experts. Not exactly an original statement, as this sort of claim has come up multiple times in the last year or so, often followed by various qualifications and the inevitable dismissals (Gary Marcus has already pointed out that this last iteration involves not a little post-shifting, and it doesn’t really stand up to scrutiny, anyway).

I’m very sceptical too, for the simple reason that modern Machine/Deep Learning models are huge correlation machines and that’s not the sort of process that underlies whatever we might want to call an intelligent system. It is certainly not the way we know humans “think”, and the point carries yet more force when it comes to Language Models, those guess-next-token-based-on-statistical-distribution-of-huge-amounts-of-data systems.[1]

This is not to say that a clear definition of intelligence is in place, but we are on firmer ground when discussing what sort of abilities and mental representations are involved when a person has a thought or engages in some thinking. I would argue, in fact, that the account some philosophers and cognitive scientists have put together over the last 40 or so years on this very question ought to be regarded as the yardstick against which any artificial system needs to be evaluated if we are to make sense of all these claims regarding the sapience of computers calculating huge numbers of correlations. That’s what I’ll do in this post, and in the following I shall show how most AI models out there happen to be pretty hopeless in this regard (there is a preview in the photo above). Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Oliver Waters

If you were a medieval peasant in the year 1323 AD, would you have believed that slavery was morally permissible?

If you were a medieval peasant in the year 1323 AD, would you have believed that slavery was morally permissible?

The odds are that you would have. After all, most people at the time saw slavery as a permanent fact of life, not an abomination that ought to be abolished. But it’s very tempting to assume that you, as a rational, thoughtful individual, could have transcended your historical setting to grasp its transcendent wrongness.

To do so however, you would have needed to reject the mainstream beliefs of your society. You would have had to think through the issue via first principles. This would include developing a coherent theory that accounted for human moral equality – a tall order, given the bulk of humanity didn’t manage this feat for another few hundred years.

It can be fun to pass judgment on the silliness of past generations, but the real work of moral philosophy is figuring out which ideas we take for granted today that future generations will look back on with the same contempt as we do for slavery.

After all, as Mark Twain warned:

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.

With that in mind, here’s a moral claim that’s obviously true, according to most people alive today:

It is always morally wrong to kill an innocent human being.

When we look at this claim more closely however, from first principles, it appears to be not only false, but a dogma responsible for a tremendous amount of unnecessary suffering. Read more »

by Mohammad Iqbal (1887-1935)

“Love is madness,” Learning said.

“Learning is suspicion and doubt,” Love said.

O Learning, do not a bookworm be, you are veiled

Love is radiant, steadfast, a pageant of life and death

Learning displays the divine essence logically; love illogically

“Question everything,” says Learning. “I am the answer,” says Love

Love is a king as well as an ascetic, dweller, and a dwelling, enslaves

Even royalty, champions life with certainty, throws open the gate of love

Laws of love forbid rest, allow tumult of storms, the joy of reaching a shore;

Forbid love’s harvest after all. Learning is Son of the Book; Love, the Mother.

***

Translated From the original Urdu by Rafiq Kathwari

by Andrea Scrima

Twenty years ago, John Reed made an unexpected discovery: “If Orwell esoterica wasn’t my foremost interest, I eventually realized that, in part, it was my calling.” In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, ideas that had been germinating suddenly coalesced, and in three weeks’ time Reed penned a parody of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The memorable pig Snowball would return from exile, bringing capitalism with him—thus updating the Cold War allegory by fifty-some years and pulling the rug out from underneath it. At the time, Reed couldn’t have anticipated the great wave of vitriol and legal challenges headed his way—or the series of skewed public debates with the likes of Christopher Hitchens. Apparently, the world wasn’t ready for a take-down of its patron saint, or a sober look at Orwell’s (and Hitchens’s) strategic turn to the right.

Twenty years ago, John Reed made an unexpected discovery: “If Orwell esoterica wasn’t my foremost interest, I eventually realized that, in part, it was my calling.” In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, ideas that had been germinating suddenly coalesced, and in three weeks’ time Reed penned a parody of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The memorable pig Snowball would return from exile, bringing capitalism with him—thus updating the Cold War allegory by fifty-some years and pulling the rug out from underneath it. At the time, Reed couldn’t have anticipated the great wave of vitriol and legal challenges headed his way—or the series of skewed public debates with the likes of Christopher Hitchens. Apparently, the world wasn’t ready for a take-down of its patron saint, or a sober look at Orwell’s (and Hitchens’s) strategic turn to the right.

Snowball’s Chance, it turns out, was only the beginning. The book was published the same year as Hitchens’s Why Orwell Matters, and the media frequently paired the two. In the years that followed, Reed wrote a series of essays (published in The Paris Review, Harper’s, The Believer, and other journals) analyzing the heated response to the book and everything it implied. Orwell’s writing had long been used as a propaganda tool, and evidence had emerged that his political leanings went far beyond defaming communism—but if facing this basic historical truth was so unthinkable, what was the taboo preventing us from seeing? Reed’s examination of our Orwell preoccupation sifts through the changes the West has undergone since the Cold War: its cultural crises, its military disasters, its self-deceptions and confusions, and more recently—perhaps even more troubling—its new instability of identity. The Never End brings together nine of these essays and adds an Animal Farm timeline, a footnoted version of Orwell’s proposed preface, and the Russian text Animal Farm originally drew from to more clearly assess the circumstances behind, and the conclusions to be drawn from, the book’s global importance. Read more »