by Oliver Waters

Two popular books released this year have breathed new life into the ancient debate over whether we have free will.

Two popular books released this year have breathed new life into the ancient debate over whether we have free will.

In Free Agents, Kevin Mitchell argues that we do, and in Determined, Robert Sapolsky argues that we don’t. To be blunt, on the big issue at hand – Mitchell is right and Sapolsky is wrong.

Despite this, Sapolsky does make a compelling case however for not excessively condemning or praising people for their decisions. The sections of his book that focus on well-evidenced pathologies that drive criminal behaviour and why policymakers should take these into account are insightful and engagingly written.

The problem is that Sapolsky extrapolates from this to an outrageously untenable position:

“We are nothing more or less than the cumulative biological and environmental luck, over which we had no control, that has brought us to any moment.”

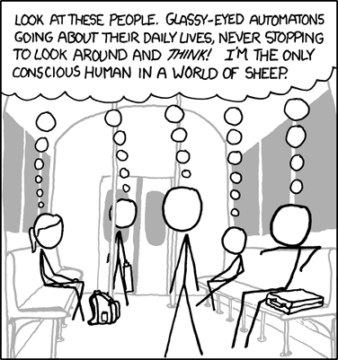

Sapolsky mistakenly infers that because there are many factors beyond your control that influence your decision-making, those factors entirely caused your decision. But all that is needed for a reasonable concept of ‘free will’ to get off the ground is that part of the decision was within your control. This of course begs the question whether a meaningful entity called you actually exists, which has causal power beyond the sum its parts. Read more »

We all naturally take an interest in the night sky. Just last week, my fiancee and I attended an event put on by the Astronomical Society of New Haven. Without a cloud in the sky, near-freezing temperatures, and a new moon, the conditions were ideal for looking through telescopes the size of cannons. To see anything, you had to stand in line, in the cold, for your opportunity to look at something for a minute.

We all naturally take an interest in the night sky. Just last week, my fiancee and I attended an event put on by the Astronomical Society of New Haven. Without a cloud in the sky, near-freezing temperatures, and a new moon, the conditions were ideal for looking through telescopes the size of cannons. To see anything, you had to stand in line, in the cold, for your opportunity to look at something for a minute.

Ron Amir. Bisharah and Anwar’s Tree, 2015. From the exhibition titled Doing Time in Holot.

Ron Amir. Bisharah and Anwar’s Tree, 2015. From the exhibition titled Doing Time in Holot.

You’ve always dreamed of foreign travel and you’re aware that there’s a long history of people doing it, and benefiting from it. But you live under a regime that closed the borders a couple of generations ago, at the same time criminalizing the act of researching potential destinations. (Many countries were dangerous, they said, and some tourists were coming home with tie-dyed shirts and peculiar ideas.) To protect the vulnerable, a War on Travel was announced. In the years since, you have grown up with little more than rumors of other cultures, climates, cuisines.

You’ve always dreamed of foreign travel and you’re aware that there’s a long history of people doing it, and benefiting from it. But you live under a regime that closed the borders a couple of generations ago, at the same time criminalizing the act of researching potential destinations. (Many countries were dangerous, they said, and some tourists were coming home with tie-dyed shirts and peculiar ideas.) To protect the vulnerable, a War on Travel was announced. In the years since, you have grown up with little more than rumors of other cultures, climates, cuisines.  Artificial intelligence – AI – is hot right now, and its hottest part may be fear of the risks it poses. Discussion of these risks has grown exponentially in recent months, much of it centered around the threat of existential risk, i.e., the risk that AI would, in the foreseeable future, supersede humanity, leading to the extinction or enslavement of humans. This apocalyptic, science fiction-like notion has had a committed constituency for a long time – epitomized in the work of researchers like

Artificial intelligence – AI – is hot right now, and its hottest part may be fear of the risks it poses. Discussion of these risks has grown exponentially in recent months, much of it centered around the threat of existential risk, i.e., the risk that AI would, in the foreseeable future, supersede humanity, leading to the extinction or enslavement of humans. This apocalyptic, science fiction-like notion has had a committed constituency for a long time – epitomized in the work of researchers like

The narrator of Alberto Moravia’s 1960 novel Boredom is constantly defining what it means to be bored. At one point, he says “Boredom is the lack of a relationship with external things” (16). He gives an example of this by explaining how boredom led to him surviving the Italian Civil War at the end of World War II. When he is called to return to his army position after the Armistice of Cassibile, he does not report to duty, as he is bored: “It was boredom, and boredom alone—that is, the impossibility of establishing contact of any kind between myself and the proclamation, between myself and my uniform, between myself and the Fascists…which saved me” (16).

The narrator of Alberto Moravia’s 1960 novel Boredom is constantly defining what it means to be bored. At one point, he says “Boredom is the lack of a relationship with external things” (16). He gives an example of this by explaining how boredom led to him surviving the Italian Civil War at the end of World War II. When he is called to return to his army position after the Armistice of Cassibile, he does not report to duty, as he is bored: “It was boredom, and boredom alone—that is, the impossibility of establishing contact of any kind between myself and the proclamation, between myself and my uniform, between myself and the Fascists…which saved me” (16). The only light in the second-class train compartment came from the moonlight, which filtered through the rusty iron grill of the window. The sun had set hours earlier, a fiery red ball swallowed whole by the famished Rajasthani countryside. I sat at the window on the bottom berth of my compartment of the Sainak Express, headed from Jaipur to Delhi.

The only light in the second-class train compartment came from the moonlight, which filtered through the rusty iron grill of the window. The sun had set hours earlier, a fiery red ball swallowed whole by the famished Rajasthani countryside. I sat at the window on the bottom berth of my compartment of the Sainak Express, headed from Jaipur to Delhi.