by David Greer

A group of island neighbours were enjoying a glass of wine in the old wooden boathouse when our quiet conversation was interrupted by an explosive Whupf! from the direction of the sea. We turned to look just in time to see the black-and-white hulk of a six-ton orca, curving gracefully into the water after a deep breath, its six-foot-high dorsal fin marking it as a mature male.

Where there is one orca, others are sure to follow. Loud blasts of spray echoed through the evening air as other members of the pod appeared, mothers with calves, juvenile males, a couple more large mature males. Some close to shore, others a half a mile out at sea. The whales’ appearance hadn’t been a complete surprise, one of our group having received a text alert from a fellow sighter in the Southern Gulf Islands Whale Sighting Network that the orcas had been seen heading west from Saturna Island towards our vantage point by Brooks Point on South Pender Island, the southernmost of the Canadian Gulf Islands, in the heart of the Salish Sea and smack in the middle of southern resident orca critical habitat.

As suddenly as they had arrived, the orcas were gone, continuing west towards Vancouver Island. Then, moments later, a much louder explosion of breath took us by surprise. This we were not expecting. Gazing seaward again, we watched as a far larger black body edged silently above the surface, like a nascent island arising from a seafloor volcano, a high cloud of fine mist dissipating above its pair of blowholes (orcas have only one). The adult humpback, forty tons give or take, perhaps more easily imagined as the size of a school bus, had passed less than a hundred metres from the point, heading northeast. Unlike the orcas, the humpback travelled alone, and there was no apparent interaction between the two species. To watch both in the space of ten minutes at relatively close range left us awestruck. Leviathan tends to have that impression on puny human observers.

Humpbacks and Orcas–Gentle Giants and Dolphins with Attitude

The contrasts between orcas and humpbacks are striking. Both are cetaceans, the animal group whose name derives from the ancient Greek word for sea monster. Cetaceans comprise two groups: whales with teeth (toothed whales) and whales without (baleen whales, including the humpback). Toothed whales include narwhals, belugas, sperm whales, beaked whales, porpoises, and dolphins. All dolphins are whales but not all whales are dolphins. The largest of the dolphins is the orca (Orcinus orca), commonly known as the killer whale, an apt descriptor for a meticulous and cunning predator with very specific tastes: chinook salmon for southern resident orcas, marine mammals for transit orcas otherwise known as Biggs orcas. Orca pods have been known to attack humpbacks on occasion, but generally only when an adult is accompanied by a juvenile, a potential meal for mammal-eating orcas.

Some of the smallest whales eat the largest prey, while the largest whales, like the blue and the slightly smaller humpback, grow huge on a diet of virtually invisible creatures, the zooplankton, the largest of which is the krill, a tiny shrimp-like crustacean that, like all plankton, drifts with the ocean currents. Teeth serving little purpose for such a diet, the giant whales have evolved mechanisms for filtering plankton out of seawater–plates of baleen (made of keratin similar to human fingernails) that descend from their upper jaws. Filter feeding requires so little effort that it is among the most efficient of feeding techniques, while producing so much energy that baleen whales grow to be the largest animals ever to have existed on the planet–far larger than any dinosaur ever to have existed, in the case of the blue whale.

The problem with being large, if you’re a whale, is attracting unwanted attention from creatures who might see you not as an evolutionary miracle but rather as a source of food, or lamp oil, or perfume (do you really want to know the source of ambergris?) or corset stays or umbrella spokes (baleen was ideal for both). Humpback whale oil was so prized that the species was hunted virtually to extinction to the point that humpbacks were no longer seen in the Salish Sea. The last whaling station in British Columbia closed in the late 1960s. Thirty years passed without a humpback being seen in these waters until the memorable day when the humpback who came to be known as Big Mama made a surprise entrance, to the astonishment and delight of local residents, in the late 1990s. Today, Big Mama and several hundred other humpbacks migrate annually from breeding grounds in Mexico and Hawaii, the mothers bringing their new calves into the relatively calm waters of the Salish Sea before continuing on to southeastern Alaska.

The abundant presence of humpbacks is one reason why the Vancouver Island region is considered one of the best places in the world to watch for whales. Gray whales–baleen whales like the humpback and similar in size–make one of the longest migrations of any animal, a round trip of almost ten thousand miles from their breeding grounds off the coast of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean and back, passing close by the west coast of Vancouver Island in spring and fall. Minke whales, one of the smallest of the baleen whales, similarly migrate between the Arctic and their breeding grounds to the south, with extended stays in the Salish Sea and along the Vancouver Island coast.

The Rebranding of the Orca from Despised Nuisance to Cherished Icon

But it’s the toothed whales that most excite the typical whale watcher’s imagination. They’re the ones with the mystique, attitude with a capital A, personality and power with capital Ps. Not for nothing are orcas named after Orcus, the ancient Greek god of the underworld. Orcinus orca might loosely be translated as “whale from hell”: killing machines that hunt in highly coordinated packs. They also live as closely knit families led by matriarchs and are considered by many admirers to be about as cute as any ten-ton creature might possibly be.

With populations in every ocean, orcas are the most widely distributed of cetacean species. Three different ecotypes inhabit the North Pacific Ocean:

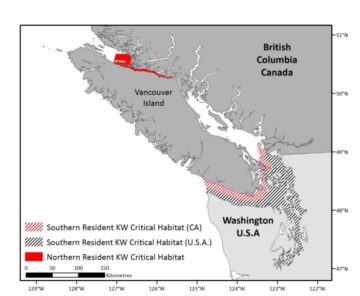

• Resident orcas, so named because their range tends to be localized around the fish populations on which they feed, whether off the coasts of Japan and Russia or of Canada and the U.S. Resident orcas in the waters of the Pacific coast of North America include Alaska residents, northern residents and southern residents, the core habitat of the latter two populations overlapping the northern and southern parts of the Salish Sea respectively.

• Bigg’s or transient orcas on both sides of the North Pacific, which feed on marine mammals such as seals and sealions, with a far more widespread range that may overlap that of residents.

• Offshore orcas, the smallest of the three ecotypes, which range far from land between southern California and the Bering Sea, preying on fish and sharks.

Small wonder that orcas were a favourite sight at marine aquariums throughout the world: in retrospect a cruel fate for one of the most intelligent and social creatures on the planet, though few people thought that way a half century ago. As recently as 1970, eighty southern resident orcas–more than their entire population today, though a fraction of the 200-plus populations that existed before the twentieth century–were rounded up like cattle in a Whidbey Island cove. Seven were taken into captivity and at least five others died. Over fifty orcas still languish in marine parks around the world, more than two-thirds of them in China and the U.S. Canada imposed a permanent ban on dolphin and whale captivity in 2019.

Fishermen in the mid-twentieth century considered killer whales such a nuisance that in 1961 Canada’s Department of Fisheries set up a machine gun post at a narrow ocean passage in the northern Salish Sea for the sole purpose of shooting and killing any orcas that might pass by. All that changed in the early 1970s, when the growing environmental movement, triggered in large part by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, set the stage for a ban on the killing of marine mammals and, more broadly, the passage of endangered species legislation such as the Endangered Species Act in the U.S. in 1973 and, much later, Canada’s 2002 Species at Risk Act.

The Beginning of the End? A Steepening Decline in the Southern Resident Orca Population

In recent decades, public perception of orcas as nuisances or as aquarium highlights has gradually shifted to concern about human impacts on their populations. Of greatest concern are the southern resident orcas, a population containing three groups or pods (J, K and L) that travel separately but interbreed. The population of the southern resident orcas has fluctuated considerably in recent decades (the corralling and capture in 1970 had a significant impact) and has steadily declined from 89 individuals in 2011 to 73 today, a reduction of almost 20%. In 2021, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reported Salish Sea chinook salmon populations to be down by 60% since the Pacific Salmon Commission began tracking salmon abundance in 1984. In marked contrast, the 34 pods of northern resident orcas include over 200 individuals, while the transient orcas that divide their time between the Salish Sea and the open ocean number more than 350, increasing by an estimated 3 to 4 percent annually.

Chiefly implicated in the decline of the southern resident orcas population in recent decades are three factors: a sharp decline in the numbers and size of their preferred prey, toxic water pollution, and noise pollution from vessels. The more the population shrinks, the greater the risk that inbreeding may further accelerate the decline as a result of reduced lifespan and fertility. Of particular concern is whether the small number of females of breeding age and mature males in the population is sufficient to maintain and expand the southern resident population.

The decline in the southern resident orca population stands in stark contrast to the steady increase in humpback numbers in the Salish Sea. Considering their different needs, it’s not hard to understand why. Humpbacks’ dietary needs are largely met by swimming open-mouthed through drifting zooplankton and setting bubble traps for the omnipresent krill. Plankton by their nature are plentiful and ubiquitous, though recent plans for a massive plankton fishery might raise questions about the future of plankton and its crucial role not only as a foundation of the marine food chain but also as a primary source of planetary oxygen—not to mention wonderment at the fact that humans have so depleted the oceans of fish that they’re now intent on mining the resource that supplies roughly half of the oxygen that sustains our beleaguered planet. Thanks to the Law of the Sea, international waters are the Wild West of the global fishing industry—no enforceable rules and first come, first served.

All baleen whales have a predictable, simple diet: zooplankton. Not so the orcas. Some orcas eat only fish, others only mammals, and there’s even an offshore orca population with a very particular fondness for the livers of great white sharks. The almost exclusive preference of southern resident orcas for chinook salmon was an eminently sound choice given that chinook were the largest of the six species of Pacific salmon–a sound choice, that is, until the twentieth century when humans developed a penchant for commercial fishing on a grand scale (while prohibiting sustainable indigenous fisheries) and a penchant for damming rivers like the Klamath and the Elwha and the Columbia, hence blocking fish passage essential to the reproduction of the species. Too often it seems, stunning developments in technology leave common sense struggling to catch up, which it typically does too little and too late. The same might be said of fish hatcheries, ostensibly designed to supplement devastated wild populations but too often used as an excuse to maintain an unsustainable fishery in addition to failing to protect or restore the old ages, large sizes, range of migration times and diversity of wild chinook salmon on which southern resident orcas depend.

Finally, toxins released into rivers and the ocean by municipal and industrial wastewater, urban and agricultural runoff, and other sources of pollutants contribute to the contamination of orca prey and orcas themselves. Efforts to quench the flow of pollutants into marine ecosystems inevitably struggle to overcome the passive obstacles of overlapping jurisdictions, political inertia and an “out of sight, out of mind” mentality. Cruise ships and other large commercial ships release their waste with impunity in Canadian waters, where no prohibition applies, in some cases patiently waiting to discharge wastewater until crossing over from American waters, where the practice is closely regulated. The inability of governments on both sides of the border to collaborate on provisions for the conservation of endangered species—conflicting regulations regarding whale-watching boat distance from orcas is an obvious example–exemplifies the challenges inherent in attempting to protect from extinction a species whose critical habitat lies within both jurisdictions. As the saying goes, nature knows no borders, and the more we are able to overcome human ones in the interests of species conservation, the better.

The Impact of Sustained Noise on Orca Communication

Out of sight, out of mind is a saying with particular relevance when it comes to considering the impact of noise on whales. Which of your senses would you prefer to sacrifice if you had to choose? Most likely not your sight.

Sight doesn’t count for much in the murky depths of the ocean. Sound matters a lot. In water, sound travels four and a half times as fast as does in air. It also travels hundreds of miles, an important consideration for a large whale courting a distant potential mate. An important consideration, as well, for a toothed whale relying on echolocation to locate and identify potential food. For humans, on the other hand, underwater noise is rarely an important consideration. We don’t spend much time listening down there. On the other hand, we’re very good at creating underwater noise, most especially with fast boats and large ships.

The level of underwater noise in the core area of southern resident orca habitat has doubled every decade for the past sixty years and is poised to ratchet up much further in the years to come as a result of the completion of an expanded Trans Mountain pipeline and the construction of Roberts Bank Terminal 2, which is expected to double the size of Canada’s largest container port. Expansion of the Trans Mountain pipeline, completed earlier this year, is expected to triple the volume of fuel tanker traffic passing through Haro Strait en route to ports in the U.S. and Asia. On May 23, a tanker named Dubai Angel, operated by Dubai-based Emarat Maritime, carried diluted bitumen from the expanded Trans Mountain pipeline in Burnaby. The tanker was chartered by Suncor Energy Inc. and was reported to be carrying 550,000 barrels of crude oil.

The impact of a passing ship can be likened to a quiet conversation in a restaurant being suddenly and at length interrupted by a roomful of shouting people, drowning any attempt to converse. Some ships are quieter than others but the average intensity of noise close to ships is over 170 underwater decibels, equivalent to 111 decibels through the air–about the sound of a loud rock concert. Studies of the impact of ship noise on humpback whales found that whales tended to stop vocalizing for the duration of the noise. Humpbacks are known for their complex songs that constantly change over time and are most frequently heard during the mating season. Though they do not breed in the Salish Sea, recent research suggests that they develop and practise new song variations here.

For the orca, not only is unimpaired communication with family members vital to survival, but so also is unimpaired echolocation for locating and identifying prey. Like owls and bats, toothed whales over the course of fifty million years evolved an astonishingly precise method of echolocation to project sounds towards an object and interpret its location and identity by analyzing the echo of their calls. A 2009 study found that southern resident orcas spent 18% to 25% less time feeding in the presence of boats than when they were undisturbed.

Petitioning for an Emergency Order Under Canada’s Species at Risk Act

The southern resident orca was listed as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act (SARA) in 2003 and under the United States Endangered Species Act in 2005. As required under SARA, the Canadian government proceeded to identify the critical habitat necessary for the survival and recovery of the southern resident orca. Critical habitat includes the attributes that sustain southern resident orcas, including adequate and available chinook salmon, a quiet acoustic environment to allow for foraging and communication, and a level of pollution that does not cause harm to the population.

Section 80 of SARA authorizes the federal Canadian cabinet to make an emergency order to provide for the protection of an endangered species, including requiring such actions as are needed to protect the species and its habitat and prohibit actions that may adversely affect the species and its habitat. In June 2024, a group of six environmental organizations petitioned the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans and Minister of Environment and Climate Change to make an emergency order for the protection of southern resident orcas and their habitat. The petition detailed a series of actions that it called on the federal government to undertake to reduce underwater noise, increase the availability of chinook salmon to orcas, and reduce the levels of pollution resulting from the unregulated discharge of ship wastewater.

The petition also called on the Canadian government to expand the distance restriction on boats approaching southern resident orcas to 1,000 meters to harmonize with Washington State’s 1,000 yard mandatory vessel buffer that comes into effect in January 2025. Whale-watching is one of the most popular tourist activities in the Pacific Northwest, and especially in the Salish Sea. The thrill of seeing a humpback whale breach or an orca spy-hop is incomparable for anyone who has never seen a whale in the wild and who has little awareness of the negative impact of the presence of a nearby boat on whale behaviour. Among their other efforts to protect the southern residents and other whales, advocates for whale conservation are encouraging whale-watching from shore rather than from boats. To that end, the Whale Trail has posted a map of over a hundred shoreline sites, from California to British Columbia, that offer a good chance of spotting whales, dolphins and other marine mammals.

The Port of Fraser Vancouver’s ECHO (Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation) program, which promotes voluntary slowdowns by ships passing through whale habitat during summer months, reported that its initiative helped reduce underwater noise intensity in Haro Strait and Boundary Pass, at the heart of southern orca habitat in Canadian waters, by up to 50% in 2023. Whether the dramatic increase in fuel tanker traffic resulting from the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion will more than cancel out those gains remains to be seen. The federal government has also designated, in nearshore areas frequented by southern residents, “interim sanctuary zones” free from boat traffic and fishing frequented by whales.

What the slowdown and sanctuary provisions lack is any assurance of permanence. They also barely scratch the surface of the recommendations included in the emergency order petition. In early August this year, concerned about the lack of response to the petition, Raincoast Conservation Foundation, one of the six submitters of the petition, put out a call for people concerned about the plight of the southern resident orcas to write to their Member of Parliament in support of the petition.

Lessons from the Past: An Emergency Order to Protect the Northern Spotted Owl

Since the Species at Risk Act came into effect in 2003, the Canadian government has issued only two emergency orders for the protection of endangered species, for the greater sage grouse in 2013 and the western chorus frog in 2016. The northern spotted owl came close in 2023, but not close enough to save itself from extirpation in Canada.

Section 80 of SARA provides that the competent minister must recommend to cabinet that it make an emergency order “if he or she is of the opinion that the species faces imminent threats to its survival or recovery”. The northern spotted owl had been in sharp decline for decades because its habitat exists only in old-growth forests, which are inconveniently attractive to the forest industry. Later, endangered as a result of that conflict, the numbers of the spotted owl were further diminished by competition by the invasive and more powerful barred owl following the spread of its range westward.

By February 2023, when only three spotted owls remained in the wild in Canada, the Minister of Environment had formed and shared the opinion described in section 80(2) but waited another eight months to recommend to cabinet that it issue an emergency order (it declined to do so), by which time only one spotted owl was believed to remain in Canada (it has not been seen since). When the Wilderness Committee challenged the delay in court, the judge agreed that the minister had failed to undertake his statutory duty, commenting, “I find it difficult to fathom how a period of more than eight months could be reasonable once the opinion has been formed…. Either the threats are imminent or not. Either the threats concern the survival or recovery of the species or they do not.”

Attempts to release captive spotted owls into the wild in Canada appear to have met with no success, with at least two captive-bred individuals found to have died not long after release into the wild. Meanwhile in the U.S., where a northern spotted owl population that has been under less relentless pressure from old-growth logging continues to hang on, the Fish and Wildlife Service has embarked on a strategy of eliminating barred owls competing for spotted owl territory.

The Northern Spotted Owl and the Southern Resident Orca

There’s one obvious parallel between the plight of the northern spotted owl and that of the southern resident orca. In both cases, the creature’s critical habitat overlaps almost completely with territory vital to an important economic sector. Vancouver is the third busiest port in North America by tonnage, and the commercial salmon fishery is the province’s most significant wild fishery. The old-growth forests that the spotted owl inhabits have for decades been the bread and butter of the forest industry. Governments typically find it difficult to pay more than lip service to protecting endangered species when doing so risks alienating industries considered vital to the economy.

On the other hand, there’s also an important difference between the two species. Spotted owls became a favourite cause of the environmental movement, but hardly anyone who lobbied for their conservation had ever seen the creature. Loggers favoured bumper stickers with slogans such as “Save a logger, eat an owl,” and they could get away with it because not a lot of people outside the environmental movement really cared one way or the other. And so the Canadian owls, out of sight, invisibly disappeared until the day when there were none.

The public perception of orcas is very different. In the past few decades, they have transformed from their predominant image as a nuisance (to fishers) and aquarium circus act to something approaching a revered icon the promised sight of which draws awestruck crowds in whale-watching boats. Dedicated whale-watchers can even learn to identify individual orcas by their patterns and the shape of their dorsal fins, as illustrated by photos of individual whales on the Center for Whale Research website. The type of guy who might have shot orcas with enthusiasm half a century ago ridicules them at his peril today.

Obstacles to Recovery of Endangered Orca Populations

The larger problem may be lack of sufficient public understanding about the level of threat posed to the southern resident orcas by the scarcity of the primary component of their diet, the chinook salmon, and, perhaps equally importantly, the impact of noise pollution on their ability to find food and to communicate with one another. Where there is lack of public understanding and motivation to act on it, lack of political will is a given.

Recent U.S. initiatives have made an important contribution to the removal of obstacles to spawning chinook salmon. These include the largest dam removal project in the history of the country with the dismantling of hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River in California and Oregon, restoring the river to its historic channel and thereby enabling access to spawning chinook salmon. On the question of chinook population recovery in Canada, the emergency order petition focuses on the need to emphasize a relocation of chinook fishing areas to river-based terminal areas. Prohibiting fishing in interim sanctuary zones where orcas are known to hunt may be a useful short-term solution to avoid human predation, but strategies to encourage the sustainability and rebuilding of chinook populations may be more important in the longer term.

While the Port of Vancouver’s encouragement to container ships, bulk carriers and fuel tankers to slow down during passage through the critical habitat of the southern resident orca (stretching from Vancouver to the western reaches of the Strait of Juan de Fuca) might have been followed by most ships to useful effect, the dramatic increase in traffic from Vancouver in 2024 may suggest the need for mandatory rather than voluntary slowdowns, together with further research on the contribution of noise pollution to the steady decline in the population of southern resident orcas.

A Postscript on Noise Pollution

My cabin in the woods of South Pender Island, at the heart of the southern resident orca range, is a good quarter mile from the shore of Haro Strait. When large ships pass a mile or more offshore, perhaps bucking an incoming tide, I not only hear them but I feel the ground underfoot shaking with their vibrations. And I wonder, how does such intense and prolonged noise, which can be audible for close to half an hour for each passing ship, affect orcas feeding in “interim sanctuary zones” far closer to the ship than I am?

I began this piece by describing a recent observation of orcas and a humpback passing by within minutes of each other near a point of land close to my cabin. Fast forward three months later, same boathouse on July 14, 2024, when the object of my observation was not whales but ships heading out to sea from Vancouver. As I watched the ships pass South Pender Island in preparation for a hard turn to port around Turn Point on the American Stuart Island, visible from my viewpoint, en route to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, my marine traffic app recorded the following details:

735 pm. Lake Stars, crude oil tanker destined for Long Beach, CA. Marshall Islands flag. Pilot boat SST Grizzly.

742 pm. Tyrrenhian Sea, crude oil tanker. Destination Longkou, China. Pilot boat SST Orca.

8:13 pm. Ultra Serval bulk carrier. Destination Dalian, China. Panama flag.

8:27 pm. APL Chongqing. Container ship. Destination Gwangyang, Korea. Singapore flag.

In under one hour, four large ships, each with its output of noise overlapping that produced by the others, each carefully manoeuvring to round Turn Point safely while keeping a safe distance from the large container ship coming the other way around Turn Point from the south en route to Vancouver. The reef off Turn Point, incidentally, has been described as the most likely location in the Salish Sea for a shipping accident to occur, a prediction I could not help but think about as two fuel tankers, each potentially transporting a payload of half a million barrels of crude oil, passed close by the point in the space of ten minutes and closely followed by a bulk carrier and container ship.

The description of potential risks to the southern resident orca population, as described in the endangered species SARA listing, does not include the impact of a half-million barrel crude oil spill on orcas. I hoped those pilot boats were paying close attention to their task, especially as the guaranteed response time to a major oil spill in B.C. waters is listed as 72 hours. High and low tides can spread a lot of oil in close to half a week.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.