by Sander Van de Cruys

If there’s one motive governing all our behavior, supervening and bringing about all our other goals or desires, what would it be? Some might say ‘survival’, pointing to Darwin’s theory of evolution. But in practice, this motive is hard to implement: It is impossible to predict or compute what, at any specific instance in time, would increase your fitness or chances of survival. It is impossible to adapt your life choices and goals to expected fitness, without getting paralyzed completely by the sheer complexity of the task —which obviously is detrimental for fitness. And if we do consider it, the motive clearly underdetermines the ways in which we pick goals and ways of life. Should I be a doctor, a lawyer, or a fricking scientist to be as ‘fit’ as I can be? The very question is absurd. Worse yet, there seem to be plenty of ways of life that blatantly go against this principle. Think about hunger strikes, vows of chastity, extremely risky occupations, or merely spending hours in computer games.

One cynical solution to this is that these are all status games. The idea is that we all want to boost our reputation in our group, and will do what gets us the rewards and recognition of our peers. Given our social nature, our fitness is closely linked to our status in our community, so we have evolved to use it as proxy that we can evaluate in the moment. I can’t help but see the current popularity of this status ‘motive’ in academic and popular-science circles as an exponent of the current online culture, prodding us to amass likes and reputation points. The message of the account is that our activities are basically empty, it is only their results that count: The reinforcements or punishments afflicted by others, who in turn have only learned to reward or punish what people like them have rewarded/punished.

The cynicism is appealing but I can’t get me to buy the content, in the wholesale way it is intended. More to the point, you know this reasoning misses something essential about our motivation, when the supposedly core target doesn’t actually feel rewarding. Any sign of an increase in status shakes me up badly, it gives me stress, instead of rewarding me to my core. Now, I acknowledge I may be atypical. I started out as a researcher of autism, and to describe that work as self-justifying would only be partly mistaken (Don’t get me wrong, I wouldn’t dare to accuse reputationalists of self-justification through science).

Still, if this reverse effect of status is a quirk, I don’t think it is that quirky. But I can see the reputationalists deflect and deflate my status-unease as some weird status-boosting device. Which means they can’t lose, nice for them but not for the science. And, not that I’m a brain-first person —ok, take the shot—, but I have yet to see the specialized status-circuits in the brain.

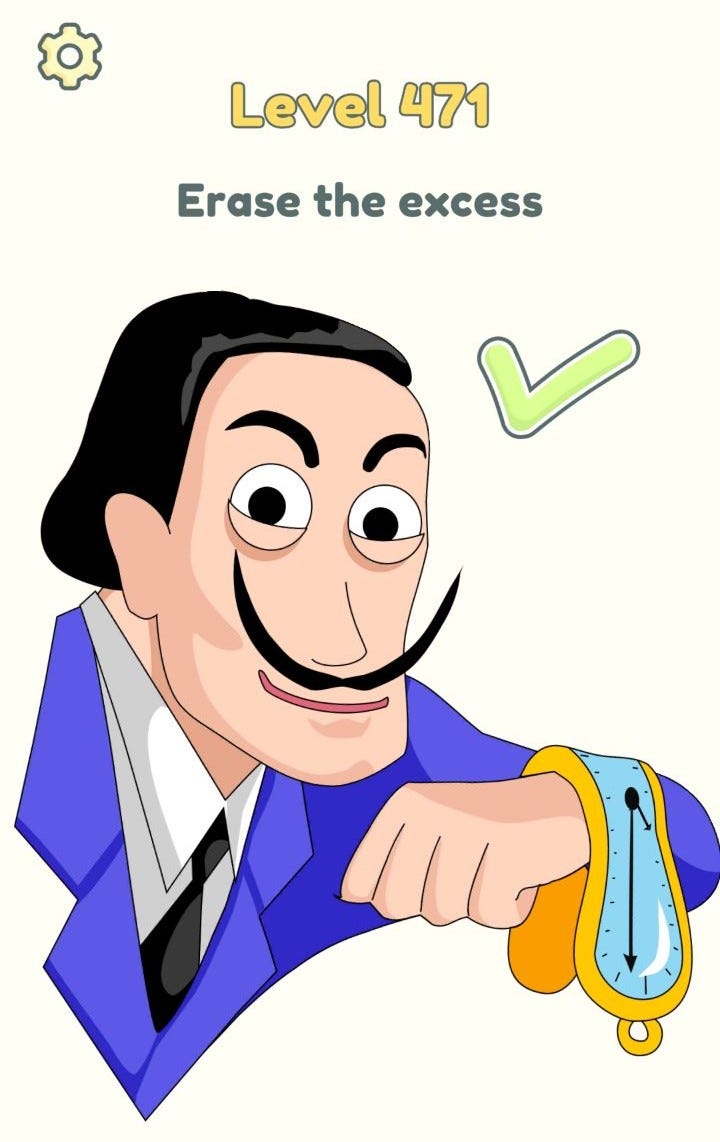

In fairness, I’m the father of six-year-old twin girls, so the importance of status hardly needs an argument in our house. But I’m seeing other, more intrinsically motivated phenomena as more pervasive. Take a silly example, a game our daughters enjoy a lot currently. It’s an app called Delete One Part (DOP), downloaded more than 100 million times according to the app store. The basic idea is in the name: You have to erase a part of the image to solve a puzzle given by the image and a single cryptic sentence above it.

It might as well be a game archetype, because it sets up artificial constraints creating an obstacle: In this case the cryptic clue, the drawing and the limited actions allowed: A gum to delete a part of the image. Despite working in a virtual environment on a smartphone, there is something really primal about using your own actions to reveal new information which solves the puzzle. It is all embedded in a very simple image and clue that create just enough challenge, just enough uncertainty, to pique intense curiosity, at least for a 6-year-old (the example above is one of the more challenging ones, so slightly misrepresenting). The curiosity incites epistemic (information-seeking) actions: Scanning the image with your eyes and using the eraser to wipe parts, sometimes revealing new clues, sometimes reshaping objects into their solution. The solution comes with what psychologists call an aha experience, a sudden insight —something that clicks together— that is the result of our puzzle-solving activity but still may arrive unexpectedly, indeliberately.

Now, the game may or may not have come recommended by the cool kids, but what drives it is clearly not status-seeking. Like so many forms of play and art, it’s hard to stop not because others reward it —though that may intensify pleasure—, but because of the very dynamics of the activity. The arc from curiosity via your own actions, to insight, relief, or uncertainty resolution. Which need is fulfilled here? Some say it is the need for cognition or knowledge, this most human of needs. Except it is not limited to humans. When I don’t feel like playing with my dog —I refuse to act as his surmountable obstacle— he’ll find the most unwieldy stick to struggle with. Not because he’s practicing skills that may become useful in the future, but for the pure love of it.

And it’s not limited to play behaviors. Biological psychologist Patrick Anselme documented numerous studies in which rodents and birds pick a non-optimal option while foraging for food rewards, if it allows them to overcome obstacles or resolve uncertainty in the process. Many people are aware of the finding that when animals get inconsistent rewards, so delivered with some uncertainty instead of perfectly regular upon their response, they will actually respond more vigorously and with more variation in whatever actions they have available. It’s not that uncertainty is liked as such or ‘appetitive’ in the psych-lingo. It’s more that uncertainty is perceived as a challenge to meet. As if there’s more rule, more consistency, more structure to find in the environment (an optimism bias in the face of the scheming experimenter).

Consider the gerbils, also described by Anselme. They get to choose between a bowl containing 1000 seeds and a bowl containing 200 seeds hidden in sand. They spent more time in and ate more seeds from the challenging bowl. This phenomenon is called contrafreeloading —a preference for earned over free food— and it’s been observed in almost any species in which it’s been tested. These animals are willing to deploy some effort and forgo a free, more profitable alternative. This happens only when the food is invisible, but a bowl of sand without seeds doesn’t do the trick.

When a reward needs to be earned, there is uncertainty involved. There’s an obstacle that needs to be overcome. But once the uncertainty is resolved, the animals prefer the free food again. Animals are prepared and even attracted to expend effort and time, because it just may lead to uncertainty reduction. Underlying this, there seems to be an implicit, optimistic expectation that their work will reveal new structure and so will increase control. But the work of meeting the challenges also is genuinely more gratifying than free rewards. It’s the puzzle-solving, not the solution that’s rewarding.

What should we call this need to clear obstacles with our own actions? It’s not explained by immediate survival needs (food or sex), let alone status. Psychologists have invented the need for cognition, for knowledge, or for learning to account for our love of things like games, art, and science. But these animal studies show that we need something much more fundamental and less cerebral than an abstracted need for knowledge. Most of us don’t enjoy reading phone books. It isn’t just about any uncertainty or knowledge.

Other psychologists proposed we like a just-right, medium level of uncertainty. This is closer to what we have here: When we talk about ‘challenge’, the word already implies some sort of balance of something that is surmountable with some effort. An uncertainty that is reducible. We like an optimal level of uncertainty because it may afford us to discover new structure, as opposed to boring zero-uncertainty patterns or equally boring static-on-tv full-on uncertainty.

There are other blanket needs that seem to cover the phenomena described. There’s the old concept of Funktionslust, “A sense of joy or wellbeing an animal (including a human) gets from doing that which it is meant to do”. Funktionslust relieves us from having to invent a new need for all things animals may like to do; my dog does not have a basic need to fetch or play any other game. All the work on uncertainty and obstacles we talked about is bounded by what an animal can do, in the niche that the species adapted to. Whatever the umwelt or preferences of the animal, it’s reducing uncertainty that allows us to do useful things or ‘funktion’.

So there’s ‘lust’ in mere uncertainty reduction, and conversely, well-being suffers when surmountable obstacles are missing. Zoo animals can suffer visibly, no matter how well-fed and well-sheltered they are. Their repetitive, ‘tragic dances’ often disappear in an enriched environment, with hidden food and playthings.

Other needs in this aisle are the need for control, autonomy, or self-efficacy. They are a bit of a black box, a placeholder for more precise understanding, but they may fit the bill as well. The emphasis is clearly on overcoming obstacles or uncertainty through our own actions. But action is a stretchable concept. When we enjoy watching a detective series with a paced delivery of clues —resolution of uncertainty— our actions are limited to attending to the right cues and matching it with possible murder plots. There’s pleasure involved and the denouement can give a sense of control. It’s similar in kind but maybe not strength to, say, playing a mystery game with overt actions, though still in a virtual world. The work to clear obstacles involves cognitive and practical acts, even if only to gather more information. So there’s a form of agency that’s mental or epistemic.

But talking about a need for agency or autonomy still suggests that what we point at is just another need to be added to the lists of principles drawn up by biologists and psychologists trying to structure behavior —now also including their own structuring! Our starting ambition was bigger and, I think, is reflected by the principle drawn out here. The principle is uncertainty reduction. But the kind that needs uncertainty or obstacles. It is about going for the active uncertainty reduction instead of the minimum uncertainty. We can’t live with or without uncertainty.

Think about it. Goals live through uncertainty. If we have complete certainty that we attain a goal state, it stops being a goal and becomes part of our habits, the structure of our being. On the other hand, when we have complete certainty that we will not reach a goal, it will also stop being a goal: We have to adapt our expectations and form another goal. I might want to be a math whiz, and think of myself as one, but when the evidence keeps piling on, I’ll have to shift my expectations. The state becomes a belief, responsive to counter-evidence, instead of a goal that remains intact in the face of obstacles. As long as we’re clearing obstacles and reducing uncertainty, we’re driven, we have a goal to do X. Goals even feed off of obstacles (until they don’t). They gain vigor in the process of overcoming obstacles.

So the uncertainty reduction principle seems prior to any sort of goal or need. It seems to be a precondition to entertain any other goal or motive. Of course, there are goals —the ones we tend to indicate as needs— that seem more absolute and independent of uncertainty: Things like food and warmth. Indeed, one thing I failed to mention about the preference for earned rewards over free reward, is that it tends to happen the most when the animal is not hungry. A very hungry rodent goes for free food, no surprises there. To bring in uncertainty again, we’d have to suppose that hunger somehow is an increase in uncertainty. That the animal builds up its own obstacle. This means being well-fed —for example, a good blood glucose level— is the state the organism expects to be in, for good reason. Evolutionarily speaking, an animal without this expectation just wouldn’t have survived for long. Developmentally speaking, the state of being well-fed expands the animal’s options and allows it to do other useful things. Not being well-fed casts uncertainty on anything else you can do.

If hunger is the best sauce, it’s because the body can become its own obstacle. Overcoming it boosts pleasure. The reward is only rewarding to the extent that it resolves a bodily uncertainty. All motivation is intrinsic motivation, because value or need is dependent on the organism’s states. Uncertainty depends on perspective: The setpoints or expectations you are forming and foregrounding. The Buddhist will nod: Ultimately, all obstacles are self-inflicted.

More precisely, reward value is about “the change in distance between a current and desired state that is afforded by any action.” It doesn’t matter whether the expected state is being well-fed or instead some self-defined or socially-constructed expectation —like a higher status. Or a short-lived, disposable goal as in games. You clamp any setpoint or goal state, and uncertainty reduction allows us to arrive there. Obstacles are essentially uncertainty that is interjected between your actions and the expected states, and so the active reduction of discrepancies between a setpoint and actual perceived state is rewarding.

So goals are just means. We adopt them to access manageable obstacles or reducible uncertainty. Just like the need to be well-fed is only a means to increase our future options, we adopt all kinds of goals to make progress in overcoming environmental obstacles through our own actions. We clear obstacles to keep our options open. It might seem counter-intuitive to try to expand our options by constraining our behavior using a goal. But in practice we need these ‘tunnels’ —bottlenecks in the state space— to be able to access more objectives and have more freedom of action in the future. Goals emerge to make the task of maximizing future freedom of action manageable, because they enable us to evaluate progress in obstacle-clearing on a more local scale, without knowing all future circumstances.

Note what happens when you overcame an obstacle and progressed to your goal. It obviously feels good, but it also increases your sense of agency. It boosts your confidence in a way that goes beyond the goal or task at hand. A similar thing can be experienced when puzzle-solving through insight. A recent study shows that we are prepared to go for more risky options when we just had an aha experience. It means we explore more options and tolerate uncertainty better.

But then why don’t goals always equal more freedom? Sometimes we do get stuck in goals badly. This tends to happen for exactly the kind of goals where we have a strong impression of goal progress, of obstacles continually being overcome. Think of the dynamics of uncertainty in gambling, with near-misses as apparently manageable obstacles. Or the hunt for status or wealth, in all the metrics our culture has invented for them. Their allure, as per above, lies in the fact that these simplified, quantifiable targets are easy to set and to evaluate our progress towards. In gambling and social metrics, local obstacle-clearing is so seductive —the need for control satisfied in the moment— that we can lose control, lose freedom, and get stuck.

We started with a principle of uncertainty reduction in the moment and ended up with a principle of maximizing future freedom. That might seem paradoxical but isn’t, which I tried to illustrate with the obstacle-clearing principle (more formal reasons for this can be found elsewhere). Rather than being a separate need or goal, this principle is what makes goals emerge in the first place, but also what makes us abandon them if they do not provide us niches of progress anymore. One concrete, computational proposal to accomplish this is called the empowerment principle which says that an agent will maximize “how much [it] can reliably and perceptibly influence the world”. Overcoming obstacles represents instances in which we make gains in empowerment.

Empowerment has been proposed as a general principle for intelligent behavior, and empowerment gains as a way to settle on goals as fruitful couplings between the organism and its environment. The elegance of this principle is in how it fuses cognition or intelligence with existential or motivational concerns. These are entangled in (first) principle. This changes how we understand ourselves but also machine intelligences.

Artificial intelligence researchers often claim that cognitive ability and motivation are independent: Any degree of intelligence can combine with any motivation or goal (known as the orthogonality thesis). On the contrary, intelligences may try to expand their options —grab control— not because this harmful goal could, incidentally or intentionally, be fitted to a supersized intelligence, but because control-grabbing might be the very core of intelligence.

Cynical philosophers might recognize Nietzsche’s will to power in all this. Maximizing our future options certainly sounds Machiavellian, but seen as the piecemeal empowerment gains —the ‘self-overcoming’—, it is a much smaller, almost sublimated thing in the moment, as we see in the game puzzle or gerbil examples above. We’ve replaced the cynicism of status with the ‘universal acid’ of power. Potayto, potahto?

But there’s a fluffy version of this principle as well, voiced by John Butler Yeats: “Happiness is neither virtue nor pleasure, nor this thing nor that, but simply growth. We are happy when we are growing.” As we saw, growth and freedom feed off of obstacles, of difference, of the ‘other’. But it’s also about absorbing and dissolving difference. The prospect is less grim, when we see that collective intelligences are also made possible by the urge to expand what a single agent can perceive and control. Presumably this is how multicellularity evolved.

So is this frail writer angling for status or power? My obstacles were the wayward words to express these thoughts, and you, the headstrong reader in my head. The greatest joy is in the joint puzzle-solving experiences, in the expansion of ideas —our mental options—, and in attuning to each other. My status, your impression, matters only in so far as it empowers my precarious writerly existence. So throw me some obstacles, will you?

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.