by Angela Starita

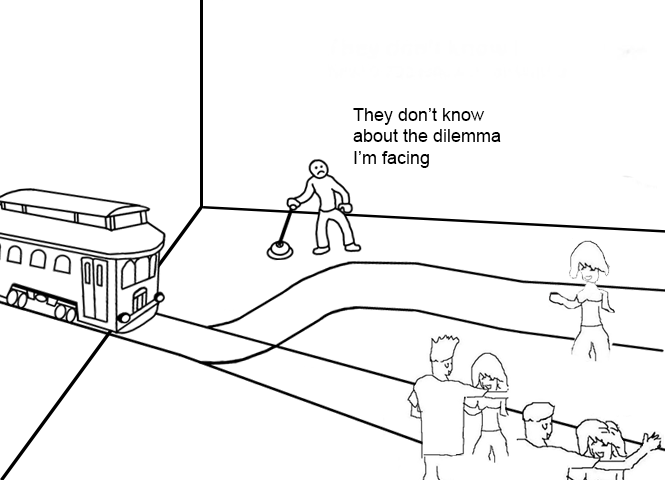

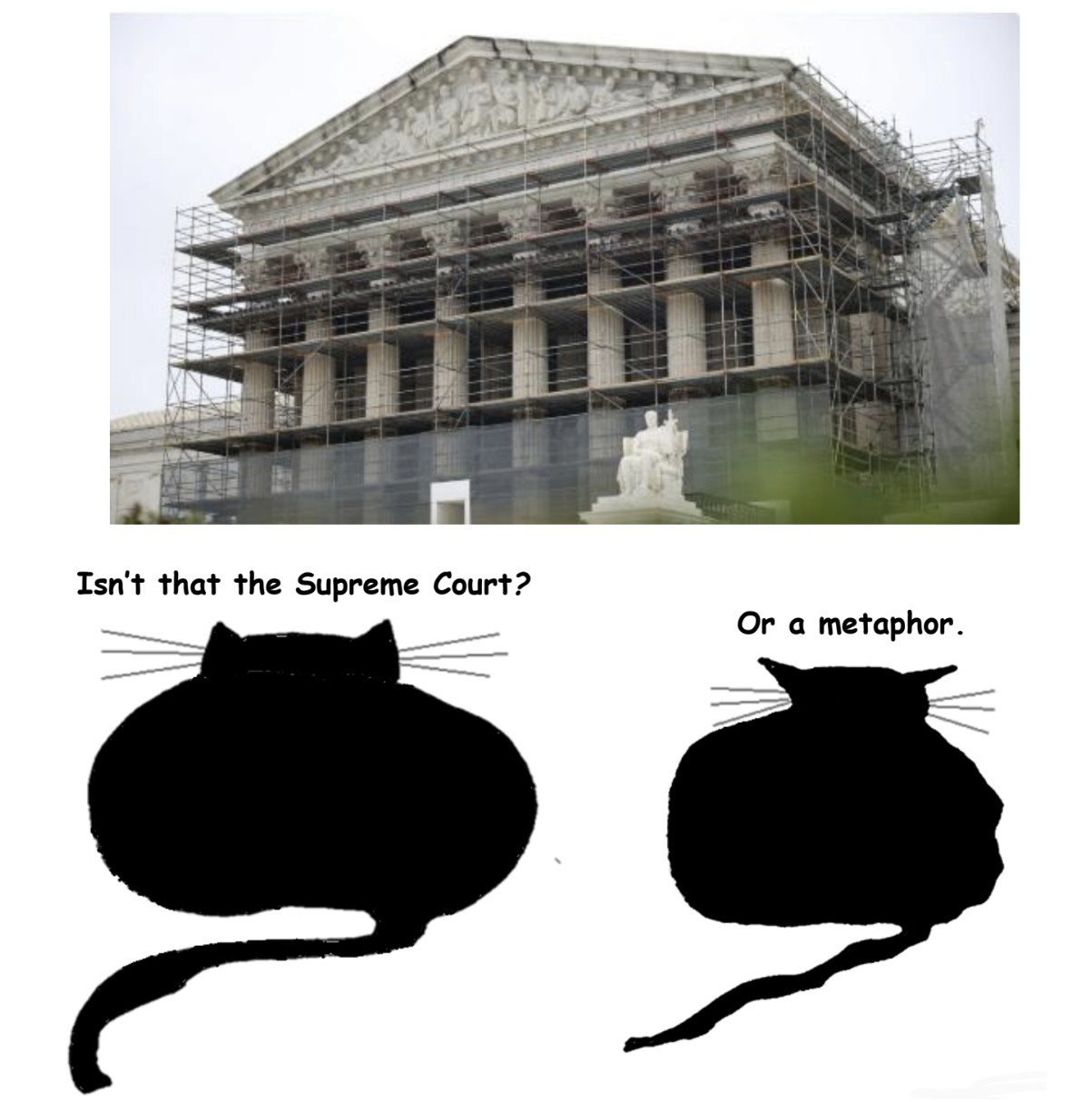

Driving through Journal Square in Jersey City with a friend, we’re both amazed by the construction that has happened there in the last two years. In this case, amazement is a form of horror: the new buildings, an array of towers, are grotesquely out of scale with the rest of the city. The worst offender is a blue-glass behemoth calling itself The Journal, the name serving as the only reference to its setting in Journal Square. As you head north, Kennedy Boulevard, the city’s main thoroughfare, veers to the left and heads up to Union City, West New York, and North Bergen. Until a few years ago, that curve underscored the Boulevard’s role as a connector, a common thread and organizing principle of those Hudson County towns, starting to the south in Bayonne. Now the approach to the Square is dwarfed by the new building, one of dozens that have gone up in a 10-block radius in fewer than 5 years. The road itself goes unimpeded, but visually the building creates a massive visual wall, intimidating, arrogant, an absolute full stop.

My friend says what he dislikes most about so much new construction is its uniformity, so unrelated to the specifics of a place. I do a bad job trying to explain the roots of un-placeness in Modernist architecture: how after the bloodshed of World War I, European architects thought they had a duty to create work that could be, as they saw it, universal. I talk about Le Corbusier’s design of the Villa Savoye as its own system, regardless of landscape, that could be plugged into almost any setting. It was like making an Esperanto for space, I say; the idea was to supersede national styles and create buildings that met people’s needs without recourse to ornament or any device that covered structural “truth.” To these architects, if our organization of space could literally foster communication, maybe prevent even war. I want my friend to see that whatever the motivations of developers, the history of architecture as disconnected object has at least some noble roots. Well, he said, I still don’t like that it has nothing to do with where it’s being built.

Solutions to the problem at the heart of our exchange—how to shape, update, and expand a physical environment with integrity—have been varied and frequently polemical: the tabula rasa approach of Le Corbusier, in some ways epitomized by Brasilia, is a frequent if misunderstood whipping boy of both urbanists and the public. And while there’s a complex and sometimes noble story behind those plans, I can’t disagree that the results of such ready-made towns—those designed by famous architects as much as the off-the-shelf developments across the country—are alienating. And of course, the blank-slate philosophy is appealing in a country where economic health is measured in housing starts. In Florida, my father’s town bought his tiny neighborhood, mostly woods, via eminent domain. Their nominal object was to create a more walkable environment by tearing down the existing houses and building new houses along with a nearby shopping street. When I asked a town manager, why not just incorporate the existing dozen or so houses into the plan, he claimed that developers only want a blank slate. Who knows if this was accurate or not, but he certainly told the truth when I asked why do this at all? “That area doesn’t generate enough income.” Read more »

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics.

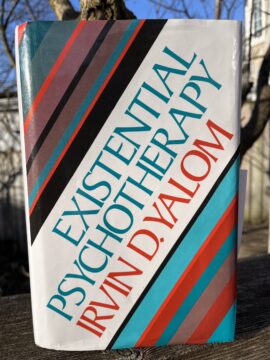

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics. About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an

About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an  Sughra Raza. Aerial composition, March, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Aerial composition, March, 2025.

Why do we fight? That question has been asked by so many in the history of mankind: philosophers, psychologists, anthropologists, historians, sociologists, political theorists have come up over and over again with explanations as to why humans fight.

Why do we fight? That question has been asked by so many in the history of mankind: philosophers, psychologists, anthropologists, historians, sociologists, political theorists have come up over and over again with explanations as to why humans fight.