by Michael Liss

April 1, 1865. For the South, the end is nearing. It was already obvious on March 4, when Abraham Lincoln delivered his magnificent Second Inaugural Address. Four weeks later, it is more obvious. For all the bravery of the Confederacy’s men and all the talent of its military leadership, its resources are almost gone. A great test, possibly a decisive one, awaits it at the Battle of Five Forks, Virginia. For more than nine months, Union and Confederate forces have been punching and counterpunching around the besieged town of Petersburg. The stalemate has cost more than 70,000 casualties, expended stupendous amounts of arms and supplies, and caused great civilian suffering, but, to Grant’s endless frustration, success has eluded his grasp. This time would be different. At Five Forks, one of Grant’s most able generals, Philip Sheridan, defeats a portion of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under General George Pickett. The price, for an army with nothing more to give, is nearly fatal—1,000 casualties, 4,000 captured or surrendered, and, even more crucially, the loss of access to the South Side Railroad, a major transit point for men and material.

April 2, 1865. The strategic cost of Five Forks is driven home. Robert E. Lee abandons both Petersburg and Richmond. Jefferson Davis and his government flee, burning what documents and supplies as they can. Lee moves his army West toward North Carolina, hoping to escape Grant and join up with Confederate forces under General Joseph Johnston. The loss of Richmond is much more than symbolic—it had also been a critical manufacturing hub, and it contained one of the South’s largest hospitals—but Lee realized Richmond was a necessity that had become a luxury. To stave off a larger defeat, he had to save his army. The last hope for the Confederacy depended on it. If Lee and his men could stay in the field, move rapidly, inflict damage, prolong the conflict, then they still had a chance. Lee thought it possible, but he was running out of everything—clothes, food, ammunition, and even men. It wasn’t just casualties that caused his army to shrink. Estimates are that at least 100 Confederate soldiers a day were simply deserting, driven by fear, hunger, and plaintive words from home.

April 3, 1865. Richmond and Petersburg fall, as United States troops occupy both. A day later, the fantastical happens. Lincoln, accompanied by son Tad and the most appallingly small security contingent, visit Richmond. The risk is stupendous—the city is burning, the harbor is filled with torpedoes, and potential assailants lurk literally anywhere. But the scene is incredible. It’s Jubilee for the slaves, some of whom fall to their feet when they recognize the tall man in the top hat. Now freed men, they gather, march, shout, and sing hymns. To tremendous cheers, Lincoln walks to the “Confederate White House,” climbs the stairs, and plunks himself down in a comfortable chair in what had been Jefferson Davis’s study.

April 6, 1865. The Battle of Sailor’s Creek, Virginia. It’s just a matter of time for Lee and his armies. He knows it, but is unwilling to yield. He has one tactic left to him, to strike a blow that temporarily paralyzes the Union army, and then rapidly pivot to join with Johnston. It makes strategic sense, but Union forces, led by General George Custer, are relentless in their pressure and faster in their maneuvers. At Sailor’s Creek (and Little Sailor’s Creek), they catch a portion of Lee’s army as it tries to cross over two bridges, pin it down, and then inflict grievous damage. Somewhere between a quarter and a third of Lee’s remaining forces are eliminated.

April 7, 1865. Grant knows he is at the doorstep. So does Lincoln. At 7:11 a.m., Lincoln telegraphs the following to Grant:

Gen. Sheridan says ‘if the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender.’ Let the thing be pressed. A. Lincoln

Grant presses, deploying the fruits of a mighty war machine that grows more powerful each day. Lee and his starving army retreat across the Appomattox River at Farmville, where they expect rations, but instead find Union forces waiting for them, as the main bridge had not yet been blown. Lee memorably loses his temper, but the situation on the ground renders anger futile. No supplies, no food, no realistic chance. It is time, but Lee is not yet ready.

Grant sends a message to Lee asking for Lee to stand down and surrender, urging him “to prevent any further effusion of blood.” Lee can’t do it. He can’t bear the anguish of surrender, and he still hopes for one more miracle maneuver, one more heroic effort by his men.

Grant presses more. He and Lincoln share a strategic insight: All the Union victories that had ended in territorial gains would not be enough to finish the war. The Union must defeat the Confederate Army in the field, and no bigger target could there be than Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Grant had to make that happen, and he had to make it happen now. Jefferson Davis, in an April 4 message, had called for the Confederate Army to begin to disburse and conduct guerilla warfare, which could prolong things for months, maybe to the point of Northern (emotional and political) exhaustion.

April 9, 1865. A final, cataclysmic battle approaches, and the Federal troops begin to surround what is left of Lee’s army. Lee needs to move before the gates close. In the early morning, he tries to go west, toward Danville, Virginia, but is blocked, mostly as a result of Union soldiers placed on ground taken on the 8th. An early morning attempt to break through Federal forces blocking the route west fades, and Lee realizes he has only two options left—fight it out with Union forces of roughly six times his strength, and likely be crushed, or surrender. It’s a bitter pill for a man whose abilities had brought the South close to a victory. He takes up the invitation of April 7, and sends a message that he wants to meet with Grant to discuss terms.

The meeting, in all its gravity, all its solemnity, becomes a critical part of American iconography—an image still resonant to this day. Lee is a man of the South, a plantation-owner, a gentleman. He approaches majestically at the agreed-upon time, in his best dress uniform, mounted on Traveler, his magnificent horse. Grant meets him there with several of his senior officers. If Lee is elegant, Grant embodies qualities most closely identified with the North—somewhat stolid, decidedly without glamour, wearing a private’s tunic, dusty from the field, boots muddy. A man of purpose. They talk briefly of old times, and Grant offers generous terms and honors, which Lee graciously accepts. Lee, with great dignity, rides off to his men to deliver the news and take the blame.

April 12, 1865. The Army of Northern Virginia formally surrenders and is disbanded. The men are sent home on parole, officers permitted to take their sidearms and horses. Food is distributed. The war is not over yet: Joe Johnston, leading the Confederate Army of the Tennessee, is still in the field, as are two smaller forces, but, for all intents and purposes, there is no hope. In fact, Johnston had already been engaged in private peace talks with his direct adversary, General William T. Sherman.

April 14, 1865. Good Friday. President Lincoln, less than a month from his conciliatory, unifying Second Inaugural Address, and just a couple of days after having proposed, in a thoughtful speech, the most measured terms for Reconstruction, attends “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre with his wife Mary. He’s a little late, but, when he arrives, the audience cheers as “Hail To The Chief” is played. He is relaxed, chuckling at the jokes, holding Mary’s hand, already planning his post-Presidential years. They will return home to Springfield, he will open up a law practice, and the couple will travel the world.

The famed actor John Wilkes Booth, angry, embittered, consumed with hatred for Lincoln and convinced that by striking a blow, he might save the South, strikes two. He points his derringer at the back of the left side of Lincoln’s head and fires. Then, with his hunting knife, he fends off Major Henry Rathbone, one of Lincoln’s guests in the Presidential Box, slicing his arm from elbow to shoulder. Screams from the box—from Mary, from Rathbone’s fiancee Clara Harris. Booth leaps over the guardrail to the stage below, breaking his shin in the process, and, in the tumult and panic, escapes. Across town, Booth’s co-conspirator Lewis Paine attacks Secretary of State William Seward and his household, almost killing Seward and his son.

The story about how Lincoln is carried across the street to William Peterson’s lodging house and placed diagonally across the bed (he was too long for it), attended by two doctors helpless to do anything (the wound was clearly mortal), has been told tens of thousands of times. As have the tales of the wailings of Mary, the sobs of sons Robert and Tad, and the dignified tears of the dignified men who had been Lincoln’s rivals and aides in life, and now served as sentinels to guard against a death they know will come.

April 15, 1865. Lincoln succumbs at 7:22 a.m. The following day would be Easter Sunday, and the New Testament allusions could not be overlooked. Nor could the confluence with an older tradition, the Passover seder. Lincoln as Moses, destined to lead the slaves out of bondage and to see the Promised Land, but not permitted to enter. These scenes, in memory all in black and white, become the counterpoint to the burnished-in-history moment of Lee’s surrender.

The historian Allan Nevins wrote:

Americans may reflect that it was perhaps fortunate for the future psychology of the nation, and its national memories during the long decades to come, that the war … should end with a clap of thunder in the sudden murder of the Chief Magistrate, … lifting the dead President to a position where he would be apotheosized by later generations, the influence of his deeds and words deepened by the tragedy.

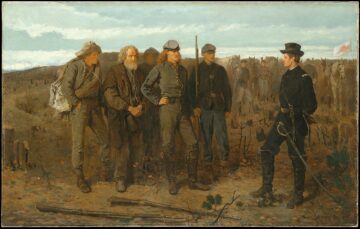

“Apotheosized” meaning, perhaps, the chalice of reconciliation might have been realized, or just a useful vocabulary for a war that Appomattox did not end? Look at this terrific painting by Winslow Homer, Prisoners from the Front, depicting the aftermath of a skirmish outside Petersburg in 1864. Confederate soldiers have lost, but they are not hopeless. See particularly the bearing of the youngest—part of a generation of those who will eventually lead the South. He is unbowed, and one wonders whether he would be prepared for reconciliation.

That did not make Lincoln’s sacrifice one in vain. The dichotomy of the dignified Lee and his valourous troops, set against the greatness of Lincoln, may have created a language those “later generations” of both North and South could adopt when they were expressing common American ideals. But it does leave us with the ultimate “what if”: Could a living Lincoln, joined (passively) by the example of Lee, have been the bridge back, and spared us the trauma of a botched Reconstruction?

This could have been a plausible outcome. At a time of great men, Lincoln towered over the rest—he saw farther and more clearly, and, by the intensity of his commitment to a set of principles, was the person best able to lead the victorious North towards magnanimity in victory.

Plausible, but perhaps not probable. Lincoln, after all, wasn’t universally beloved—and a lingering disdain and even animus manifested itself during his mourning period. In the South, reaction was mixed. There were the happy vengeful, and a few even thought Lincoln’s death would be a miraculous turning point in the War. Some of the Southern newspapers exulted, and Jefferson Davis reportedly said, “If it be done, it would be better that it be well done.” But many others (Lee, Joe Johnston, Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens, and former Supreme Court Justice John Campbell amongst them) worried not just about the anger of the North, but also the loss of Lincoln as a buffer—they knew he stood between them and a radical empowered Congress.

Lincoln’s detractors were not limited to the South and the ever-active Northern Copperheads. A great many Northern Democrats of the business classes wanted to do business, and not annoy themselves with destructive arguments over “principles” like Emancipation. Also not to be underestimated was the potency of the racial issue: the fact that Northerners did not own slaves did not mean they were in the least bit racially tolerant, and Lincoln, with his ideas about the equality of all men, did not exactly afford them comfort. Their support for Lincoln, if it was support at all, would be tepid. Perversely, the same applied to Abolitionists—they had always wanted more and sooner, and Lincoln almost always disappointed them. The “what if Lincoln had lived” question might have been an interesting experiment in the limits of centrism: Could Lincoln’s core temperamental and ideological moderation, his reverence for the ideals of the Founders, revitalized at Gettysburg, have been the basis for a successful Reconstruction, or might those very qualities have made him too hot for some, too cool for others?

To place Lincoln in the public’s esteem, we will have to content ourselves with what history tells us, rather than what history could have been. The South could reasonably be expected to be grudging in its respect, as could many of the other “special interest groups.” What about the rest of the world? The Brits were pretty bad at offering condolences—the ruling classes there saw the South as more of a kindred spirit. Others, however, took a different view, something closer to the heart. Argentina declared three days of mourning. In Chile, it was reported that strong men walked the streets in tears, stricken by the news. Forty thousand Frenchmen subscribed to have a medal struck (with France’s heart) to send to Mrs. Lincoln.

Ultimately, it was the gestures by common people that attested to Lincoln’s greatness. Small organizations sent their sympathies and good wishes—obscure guild members, and singing societies. Cotton brokers in Liverpool and Theology students in Strasbourg. The Working Class Improvement Association in Lisbon. The Men’s Gymnastic Association in Berne and the Fraternal Association of Artisans of Leghorn, Italy.

Why? Many saw Lincoln as one of their own, a person whose virtues were beyond country and beyond politics. For a decent, good-hearted man to take up the burdens of this terrible Civil War, and lead the country through it, they would come. Here, his funeral train attracted seven million to gather on the sides of the tracks to see it pass on its way home to Springfield—for 1700 miles he was never without an escort of mourners. There, they lined up for hours to see him as he lay in state, wiping rain and tears away from their faces.

They grasped something about Lincoln that eluded the rich, the powerful, even the merely tactically ambitious—Lincoln had always stood with the common men and women, regardless of their place in society. Now they stood with him. A remarkable, aching tribute came from the residents of Lahaina, in the Hawaiian Islands:

[the people] weep together with the republic of America for the murder, the assassination of the great, the good, the liberator Abraham Lincoln, the victim of hell-born treason—himself martyred, yet live his mighty deeds, victory, peace, and the emancipation of those despised, like all of us of the colored races.

Lincoln despised no one, no group. He embodied a different type of tolerance, one so subtle that it is almost impossible to describe accurately. His was the tolerance of common courtesy, of accepting differences without embracing them and imperfections with the self-knowledge of your own. He did not demand that you look like him, think like him, worship like him, or vote like him as a predicate to earning his respect for your basic human rights.

That kind of man helped win the Civil War. Could that kind of man navigate a difficult peace when so many were reluctant to follow? We, of course, will never know, but, in thinking about him and the universality of the way he lived his public life, we are reminded of the description of the exchange Lincoln and Frederick Douglass had, on the evening Lincoln delivered his Second Inaugural Address:

Douglass; there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more. I want to know what you think of it.

The response?

Mr. Lincoln, that was a sacred effort.

Let that be his legacy, “a sacred effort.”