by Kyle Munkittrick

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new book, Abundance, inadvertently exposes a blind spot in our collective moral calculus. In making their case for a better politics, I think they’ve also, as an accidental by-product, solved the infamous Trolley Problem.

Abundance argues that improving the supply of things like housing and energy is good on its own term and that material abundance can help address collective problems, like homelessness or climate change. The choice between allowing people to sleep on the streets in tents or forcing them into shelters is, as Klein and Thompson point out, a false dilemma caused by poor housing policy. The choice between growth and progress vs climate change is a false dilemma caused by poor energy and construction policy. Klein and Thompson are, justifiably, focused on the political thorniness of these issues, but, in their efforts, also demonstrate something startling: they implicitly demonstrate that material abundance can obviate moral quandaries.

The Trolley Problem is so well known and over-explored it’s easy to forget that it is relatively new. The Trolley Problem is a modern moral dilemma. There are no trolleys in nature. You cannot replace the trolley with a bear or a hurricane or an opposing tribe—those things do not run on tracks, their brakes can’t go out, and there is no simple lever by which you choose their behavior. The Trolley Problem is a problem of technology, yet none of its solutions are allowed to be.

The Trolley Problem is, as it is usually presented, a false dilemma. There is no correct answer to the problem; both options are tragedies, neither better, regardless of permutations. Even being asked to make the choice is morally corrosive (as I’m sure Philippa Foot and Judith Jarvis Thompson would agree). The Good Place demonstrates this to absurd comedic effect.

It is the ridiculous Sisyphean repetition of The Good Place trolley episode, along with our own decades of obsession over the problem, that resonates most with Abundance. What if instead of trying to figure out if one or five is the better choice with infinite variations and philosophical arguments, we just fix the trolleys? This is the core insight of what I call Moral Abundance—the idea that technological and material progress can eliminate moral dilemmas entirely.

Consider climate change. Abundance not only recommends choosing among existing tech like moving from coal to solar, but also explores near-future examples like cultured (aka lab-grown) meat. This tech does exist, but it’s niche, nascent, and expensive. It’s also unsettling and popular for politicians to oppose it. But Abundance, correctly, holds up cultured meat as a worthy goal because in addition to helping address climate change (agriculture is a major contributor), it would also allow us to effectively end the moral stain that is factory farming.

Yes, we can remove factory farming by just banning it, but that’s a political non-starter. It would mean less food choice (not great), inequity where only millionaires get steak, eggs, and bacon (sad!), potential food shortages (bad) or, worse, famines (very bad). In a Trolley Problem-esque version of the dilemma, the question we’re asked is who should suffer, animals in cages or people in famine?

The answer of Abundance is neither. We can obviate the question with progress. The implicit claim of Abundance is that material abundance not only makes things cheaper, easier, or higher quality, but also makes it easier for people to be better. Abundance, yoked to technological and social progress, can mitigate root causes of moral dilemmas, obviating them.

To formalize this concept: Moral Abundance proposes that material and technological abundance, by removing constraints or scarcity, can mitigate moral issues and render some specific moral questions effectively obsolete. By changing the landscape of debate, abundance makes it easier for everyone, on net, to be better than they would or could otherwise be. Moral Abundance shifts our attention from the moral question in front of us to the opportunity to eliminate it all together. The solution to the trolley problem is not one track or the other, but to invent, build, and deploy safer trolleys.

Moral Abundance is, in part, about recognizing that our environment can be moral, and we can choose to intervene. Noah Smith makes a compelling political argument that anarchy is not welfare, that is, allowing people to be anti-social doesn’t help them or society. We can make the same argument about nature: chaos is not amoral. Nature or the status quo harming people is bad. It is evil, even though there is no actor. We tolerate it because we believe cannot control or change it. Moral Abundance challenges that helplessness by recognizing our capacity to reshape the context of ethical dilemmas, not just navigate within them.

Moral Abundance also recognizes the function of time and progress to create a kind of chronological moral luck. By virtue of living today it is easier to be good, because of massive social and technological progress, than it was a century ago. Ada Palmer’s Terra Ignota series, along with The Culture and Star Trek in the pantheon of great post-scarcity fiction, demonstrates this moral luck. Despite deep flaws, the future of Terra Ignota is more moral than our own society on almost every measure because material constraints (of health, of travel, of energy) are all but eliminated. Moral Abundance also results from improved circumstantial moral luck. Abundance reduces the possibility of scarcity forcing individuals into tragic choices—the bad luck of facing that specific unavoidable dilemma. Moral Abundance reminds us that material, social, and technological progress can be powerful inputs to moral progress.

As such, Moral Abundance invites ethicists and philosophers to consider the practical world of technological development. Elements of Moral Abundance are already present throughout philosophy. The capabilities approach developed by Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen offers a particularly useful framework. “Capabilities” here are real freedoms—the actual ability to choose different ways of living. By focusing on what people can actually do rather than abstract rights or resources alone, this approach naturally aligns with Moral Abundance’s emphasis on expanding practical moral options. A surprising example comes from Shulamith Firestone, who explicitly argued in her Dialectic of Sex that technological advances like artificial wombs would be necessary for true gender equality. Firestone has one of the first, clearest examples of identifying a particular technology as a direct solution to a seemingly intractable moral issue.

More recently, bioethicists like Julian Savulescu, Ingmar Persson, and Thomas Douglas have proposed “moral enhancement” technologies to improve human ethical capacities directly. These could make us less selfish, more tolerant, and less neurotic, among other pro-social benefits. And at the bleeding edge of technology, Amanda Askell is working not to merely constrain AI, but to instead actively shape its development toward moral ends. These philosophers are practical experts in the relevant sciences (neuroscience, biochem, machine learning) and have put their reputations on the line advocating for specific paths that technology should take.

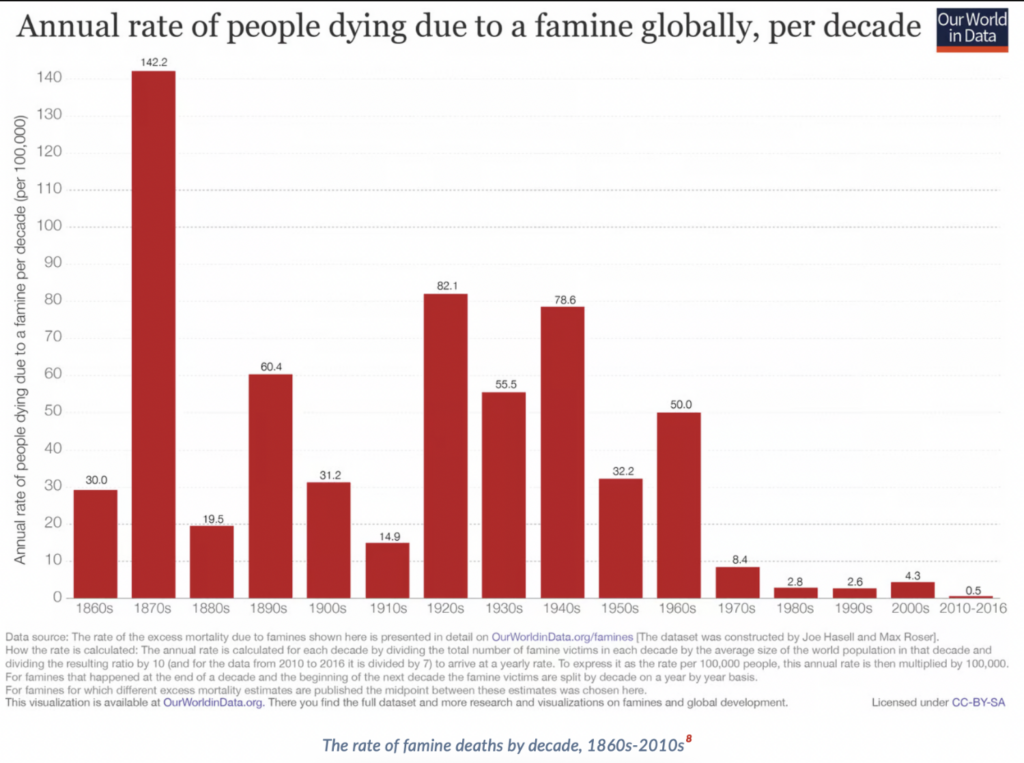

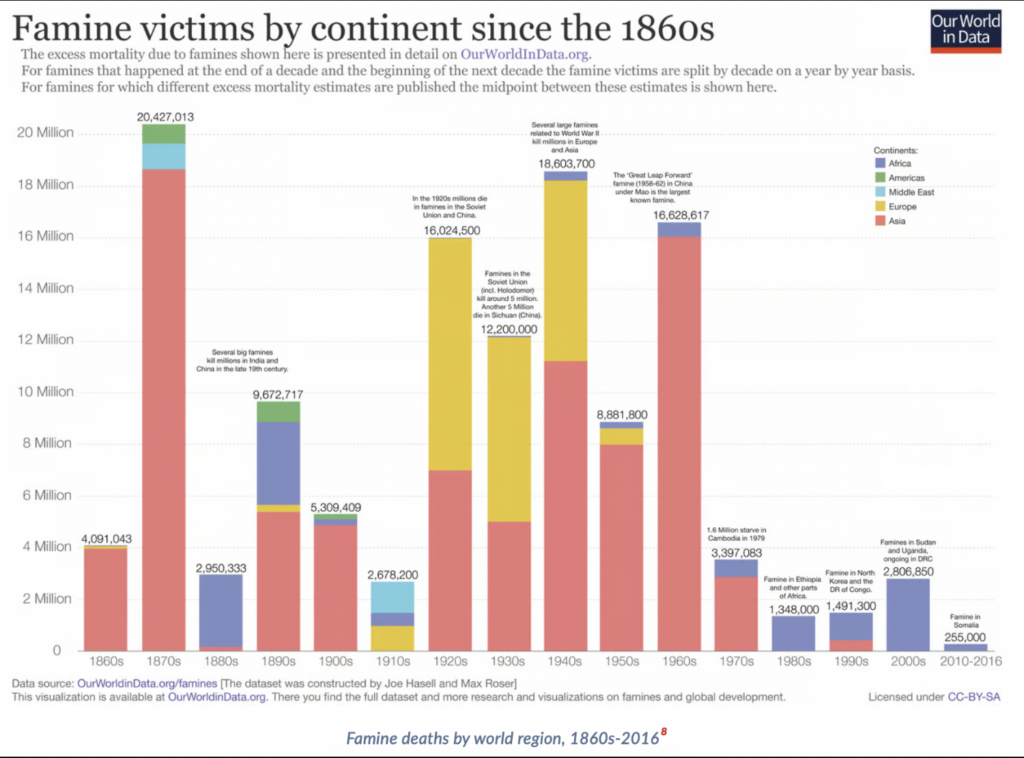

So what path should food production take to achieve Moral Abundance? Before factory farming and the green revolution, famines were common due to the chaos of nature. As factory farming, the green revolution, the refrigerated shipping-container, GMOs, and global free-trade improved and matured, famines basically went away. Consider these two graphs below from Our World In Data on Famines.

Deaths per 100,000 people, globally, due to starvation, came down 90% from the 1960s to the 2010s. Absolute deaths are down 98% on the same time horizon. Does this mean we have perfect global food equity? No, but, my goodness, I’ll take a near order of magnitude reduction in absolute and relative deaths due to famine in a 50 year period over nothing.

History is full of examples of Moral Abundance at work. Kerosene and electricity did more to end whaling than any concerted conservation movement. Legal systems of justice obviated dueling and honor culture. Automation and safety measures has made mining, once famous for tolerating carnage, come to see every death or injury as a preventable tragedy. Anesthesia and sanitation made surgery all but pain-free, orders of magnitude safer, and dramatically more effective. Long-acting reversible contraception (IUDs, Nexplanon, etc) has done more to reduce unwanted and teenage pregnancy than centuries of religion, cultural norms, and after school specials. Each dilemma was its own trolley problem (light vs whales, coal vs miners) obviated by progress.

But while famines have faded into history, the horror of factory farming has grown. This is critical to remember: abundance can create more moral good overall even if new moral wrongs emerge. Before the 20th century, famine was a given, there was no alternative. As disorienting as it seems, that we can even ask the question, “Who should suffer, animals in cages or people in famine?” is progress. Moral Abundance pushes us to continue our progress, to look past the initial false-dichotomy, and to ask weird questions about our future, like What if we could get the meat without the animal? One question obviates the other. Abundant, affordable, high-quality cultured meat could keep famine rare, reduce climate impact, and reduce animal suffering.

Cultured meat, you might rightly point out, exists today and we don’t have these benefits. Transitions to new technologies are uneven. Innovations often start out as rare, limited, and expensive luxuries—they are not abundant. Cultured meat will likely become cheaper and more ubiquitous, just like cell phones did and EVs are becoming. Which, in turn, will make it easier to eat factory-farmed meat less, just as EVs make it easier to pollute less. Material abundance is a necessary (but not sufficient!) condition for Moral Abundance.

This also does not mean that any form of abundance, such as cultured meat, only facilitates moral goods. New technologies destabilize things (that can be bad), lead to surprising new problems (e.g. phones are addictive), and during the transition, can be inequitable (e.g. EVs are still often a ‘luxury’ and not an option for many). Moral Abundance doesn’t presume utopia or mindless techno-optimism. Moral Abundance’s pursuit is to give ourselves more options and thereby make it easier to be better. And it does not happen in a vacuum. Klein and Thompson vociferously argue that high state capacity and a flourishing, dynamic private sector combine to facilitate the conditions under which Moral Abundance is possible.

As we build toward Moral Abundance, we might envision a future where our descendants no longer wrestle with the ethical quandaries that consume us today—not because they’re inherently wiser (though, if enhanced, they just might be), but because the technological foundation we lay now helps create a world where factory farming, climate catastrophe, and resource scarcity have become historical footnotes rather than pressing moral emergencies. Moral Abundance challenges us not just to build a better future, but to build a future in which we can be better.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.