by Rafaël Newman

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics.

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics.

No, our house religion was social democracy.

Our family commitment to sexual and racial equality, socialized medicine, decolonization, and government regulation of the market was manifest, of course, in a geographically and historically conditioned form: in electoral loyalty to the NDP, Canada’s mainstream progressive party, founded in 1932 as the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and renamed the New Democratic Party in 1961. Our family credo held that the Liberal Party of Canada, known as the Grits, might look progressive enough, but their instincts would always be pro-business; any socially progressive policies they may have championed had been forced on them by their marriages of parliamentary convenience with the New Democrats. As for the Tories, Canada’s Conservatives, they were simply out of the question for progressives: it’s in the name. My choice of the NDP in the ballot box, when I came of voting age, was thus at once more, and less, than a deliberate commitment: it was a reflex, almost an instinct. It was second nature.

My first proper induction into retail politics was at the age of 14, several years before I was eligible to vote; and it involved working on a by-election campaign for the local NDP candidate in our Ontario riding of Broadview. Before we moved east to Toronto, from the Vancouver suburbs where we spent the mid-1970s, I had already twice ventured into political activism: once visiting a meeting of the local Trotskyist cell, where I was amazed to encounter my high school French teacher; and once at a rally for divestment by Canadian banks in then-apartheid South Africa. (This is not counting my fabled instrumentalization as an infant, when my mother protested the sale of Californian grapes at our local Steinberg’s grocery store in 1960s Montreal, holding me aloft, like Andromache for extra pathos, as she cited Cesar Chavez and the NFWA.)

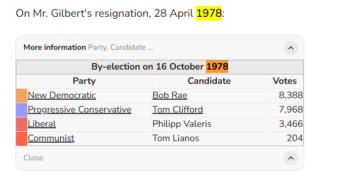

Now, in 1978, freshly arrived in our new home in east-central Toronto, I was encouraged by my parents to volunteer in support of Bob Rae, who would go on, at 30, to win his first federal seat for the NDP that October and would remain a member of parliament for over two decades.

My younger brother Adam, not yet 13, joined me, on a crew distributing and mounting lawn signs advertising Bob Rae as the NDP candidate. We reported for duty and were assigned to accompany another volunteer, an older man with a pickup, making the rounds of a Greektown neighborhood not far from our cooperative housing estate on Bain Avenue, across the Don Valley. We loaded the signs—cardboard placards in the party’s signature orange stapled to wooden stakes—into the back of his truck and set off, filled with pride in our fulfilment of a family duty.

It wasn’t long, however, before our allegiance to the common faith was tested, when we were confronted with the contradictions of political affiliation, the notorious strange bed-fellows created by common travail. Barely pulled away from the curb, our driver revealed himself to be an advocate of the “socialism of fools” as he began to rail against the alleged Jewish cabal behind Pierre Trudeau, then still Liberal prime minister of Canada. Adam and I were silent, struggling inwardly with the need to protest his outrageous antisemitism but cowed by the man’s seniority, ashamed of our own craven inhibition and terrified that our diffidence would be understood as complicity by our vicious companion. Perhaps, too, we were discomfited by an absurd and secret fear: that there was some truth in the conspiracy theory, since our Jewish grandfather, an outlier in the extended family, had been voting for the Liberals since he came of age in Canada. Our Zaideh’s extravagant veneration for Trudeau was largely due to the prime minister’s declaration of the War Measures Act, during the October Crisis of 1970, in response to terrorist violence by the FLQ, a Quebec separatist organization, whose ethnonationalism was perceived as a threat to the province’s Jewish community.

At any rate, we were mollified when, some days later, on the eve of election day proper, we attended a rally for volunteers to “get out the vote” at which we were addressed by Stephen Lewis, the charismatic leader of Ontario’s provincial NDP, the son of David Lewis, a founding NDP politician—and himself a Jew. And, in the years since, Bob Rae, to all appearances a typically Anglo-Scottish Canadian, has discovered and publicly discussed his own partly Jewish ancestry, and has married into a prominent Jewish-Canadian family.

However, another, more significant development in Bob Rae’s political career since that 1978 by-election proved to be a greater test of our family faith, as well as a symptom of a perennial problem for supporters of Canada’s third party, after the Liberals and the Conservatives, who have alternated in federal power for most of Canada’s existence. After serving as the premier of Ontario from 1990 to 1995, having formed the first provincial NDP government east of Manitoba, Rae left the New Democrats and returned to the Liberals, with whom he had been affiliated as a young man. He was interim leader of the federal Liberal Party from 2011 to 2013 but never actually served as prime minister; the culmination of Rae’s career today is his service as Canada’s Ambassador to the UN.

Bob Rae’s move was an outgrowth of the NDP’s pursuit of a progressive agenda at the federal level, typically in alliance, if not coalition, with the centrist Liberal Party against the Conservatives. At some point, it was inevitable that members of the right wing of the NDP, like Rae, would see their fortunes better served as bona fide Liberals, with a chance of holding actual power, rather than as eternal also-rans for the NDP, delivering tireless Jeremiads on the excesses of capitalism while gradually forcing the Grits to adopt socialized healthcare and other progressive programs. Rae was evidently keen, after his tenure as provincial leader, to taste federal power, which had always eluded the New Democrats; and his ideological discomfort with the leftward shift of the NDP during the early years of the new millennium made “crossing the floor” easier.

This is the predicament currently facing my family still in Canada, where I have not been a resident for decades and thus am no longer eligible to vote. With the recent political upheavals caused by the breakdown of agreements between the NDP and the Liberals last year, the resignation of a high-ranking member of Justin Trudeau’s government, and the prime minister’s own departure this past March, following a steep decline in his approval ratings, the mounting fortunes of the opposition Conservative Party have suddenly been reversed and the Liberals, under the leadership of Mark Carney, bid fair to win the snap election called for next week, on April 28.

All of this is given added urgency, of course, by the second election of Donald Trump, by his scattershot policy of economic aggression, and by his menacing talk of annexation. Lifelong NDP supporters are thus being called upon not to split the center-left vote but to plump straightforwardly for the Grits, and thus potentially give them a majority: so as to properly defeat the Tories under Pierre Poilievre, their reactionary, Trump-lite leader, and to strengthen the hand of ex-central banker Carney when he deals with threats, economic and otherwise, from the south.

A childhood friend from Montreal, now a senior executive at a left-leaning polling company in Toronto and a lifelong NDP supporter, has been posting darkly about the dangers of such strategic voting:

If you genuinely feel you need to hold your nose and vote for Mark Carney as the “lesser of two evils” in the election that is your right and, depending on what riding you live in, it may make sense. But don’t try to fool yourself into believing Carney is some sort of “closet social democrat”. He is NOT. He is a right of centre, neoliberal, “blue grit”, defender of the status quo who will likely represent a throw back to the Paul Martin austerity years of the 90s. Is he far less of a threat to the future of our society than Pierre Poilievre? Absolutely! Does that mean he will be a good PM who will actually improve anything in Canada? All I can say is Caveat emptor. To me he simply represents a bullet being dodged. Some people say Carney has said a few nice things about how he actually believes that climate change is happening and that something should be done about it—you know who else wrote and said a lot about being “deeply concerned” about climate change? Boris Johnson. Big deal.

It does feel like the rise of rightwing extremism, around the world and especially in the US, is frightening progressive voters (those who have not yet been alienated by divisions on the left over Gaza or Ukraine) into a closer compromise with otherwise anathema centrists. Jagmeet Singh, the leader of the federal New Democrats, is judged to have fared well enough in the recent leadership debates among the four major parties (the Grits, the Tories, the NDP, and the Bloc Québécois, a regional party which, like the Bavarian CSU in Germany, absurdly runs for federal office)—but Singh’s insistence on the importance of preserving and expanding Canada’s socialized healthcare system is widely accounted a parochial distraction from the “grave existential threat” of tariffs and invasion. And in any case, the idea of sending a youngish, turbaned career politician of color to “negotiate” with Trump and his coterie of hyenas, rather than an older, more conventionally attired, WASPy central banker, evidently strikes fear into the hearts of the most committed Canadian social democrats.

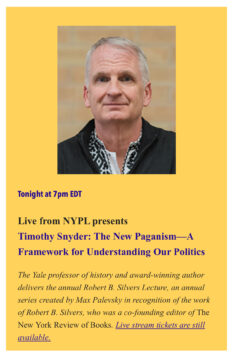

But who can say what is the best progressive approach to the present American regime, whose hideous character is still in the process of revealing itself? This past April 1, on the eve of Trump’s disastrous “Liberation Day” of universal tariffs and economic chaos, the celebrated historian Timothy Snyder attempted an archeology of the Trumpian phenomenon as he presented this year’s annual Robert B. Silvers Lecture at the New York Public Library. In “The New Paganism—A Framework for Understanding Our Politics,” Snyder presented his theory of the current rise of authoritarianism, in the United States in particular, as the rebirth of an earlier phase of western societal organization, now in a new form. Snyder elaborated what was effectively an anti-Hegelian dialectic, in which thesis and antithesis would not culminate in a “beautiful Aufhebung,” but rather give rise to a farcical distortion, an afterbirth of history in which the features of an allegedly restored Golden Age are recognizable only as grotesque negations of their putative ancestor.

With a model of history so grand and sweeping, he joked, that it would relieve him of the standard obligation to write up his lecture as a contribution to the sober and rigorous New York Review of Books, Snyder sketched what he described as a succession of “three natures,” or Umwelten, manifest as a series on the timeline of European history.

With a model of history so grand and sweeping, he joked, that it would relieve him of the standard obligation to write up his lecture as a contribution to the sober and rigorous New York Review of Books, Snyder sketched what he described as a succession of “three natures,” or Umwelten, manifest as a series on the timeline of European history.

Snyder’s first nature is exemplified by the pagan culture of the Vikings, in which language is used to communicate with the world, not control it, oracles are mysterious and unpredictable, sacrifice (of humans) has a crucial political function, value is a numinous property inherent in material belongings, displayed in potlatch-like festivals of gifting, and capable of being transported into the afterlife, and charisma is a tangible quality indispensable to the valiant warrior-headman.

His third nature, the “New Paganism” of his lecture title, is in every point both a revival and a travesty of the first, a world in which language, having come in the intervening period to control the world rather than communicate with it, now conveys untruth; in which oracles are the computer devices we carry around and consult at every turn, rendering us the tools of an alliance between oligarchies, whether the hydrocarbon (Putin) or the digital (Musk); in which sacrifice has lost its sacred meaning to become the pure enactment of “sado-populism,” as the abduction and incarceration of “illegal immigrants” is filmed and broadcast for snuff-porn enjoyment; in which value is synonymous with monetary worth, and is to be amassed and preserved, rather than exchanged or distributed; and in which charisma has become the signal property of a new type of Viking chief, one who displays his power not on the battlefield, in feats of tremendous personal courage, but rather in cynical cowardice, by commanding his minions to carry out acts of cruelty and violence in his name, by allying himself with erstwhile enemies, and by turning on the weak in a gesture of half-understood Nietzschean transvaluation.

Between the two of these Umwelten, the antithesis of both and the filter through which the first is refracted as the monstrous third, is Snyder’s second nature: the world of monotheism, the renunciation of human sacrifice for its symbolic enactment, an anthropocentric relationship with nature pursued by means of linguistic control, and the decalogic ethics that would eventually give rise to humanism, the Enlightenment, and modernity. And in addition, if very distantly, via periodic, chiliastic appeals to an egalitarian “primitive Christianity,” it has been the wellspring of social democracy.

It was clear that Snyder was not calling explicitly for a return to this intermediate phase, characterized as it was by the very chauvinistic Christianity and extractive colonialism that have helped to produce our current malaise. But he did issue a plea for a revived humanism, for intensified study of the humanities, as a counter to the present regime of anti-humanism, indeed inhumanity. The plea came as he closed his remarks with a statement regarding his recent move from Yale University to the University of Toronto: contrary to popular belief, he explained, he had not decided precipitously to leave the United States upon Trump’s election, but had in fact been planning the move for some time, and for personal reasons. He would still be making appearances in the country of his birth, he promised, practicing the humanities there as elsewhere, and running the risk of harassment, or worse, by the current regime. And he urged us to put aside our differences and unite, to make common cause: for it is a typical fault of the American left, he noted, that it has been more willing to “set upon” its own adherents, than to join forces against a common opponent.

Tony Judt, Snyder’s late mentor, remarked ruefully in Ill Fares the Land: A Treatise On Our Present Discontents (2010), one of his last works, that social democracy has seemed to enjoy its greatest success in small, ethnically unified countries—his examples, as it happens, are drawn from the latter-day Scandinavian Umwelt of Snyder’s “first nature”—since it can be hard to get people to feel the selfless compassion and solidarity necessary for social justice with Others, with people unlike them in descent and custom:

The kind of society where trust is widespread is likely to be fairly compact and quite homogenous. The most developed and successful welfare states of Europe are Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands and Austria, with Germany (formerly West Germany) as an interesting outlier. Most of these countries have very small populations: of the Scandinavian lands only Sweden tops 6 million inhabitants and between them all they comprise less people than Tokyo.

Canada is rather larger than most of these, and certainly more heterogenous. However my friends and relatives on the left vote on April 28, whether strategically by riding or ideologically by conviction, I hope they will be able to unite with other progressives following the election, whatever its outcome, and to demonstrate the possibility of social democracy in a country as ethnically and culturally diverse as ours, in what will surely be a painful contest with a southern neighbor intent on evacuating its own, and others’, commitment to these very same shared values. Let us hope for the construction of a new and different third Umwelt, drawing its power in part from the humanism that has been second nature to my Canadian family.