by Kyle Munkittrick

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new book, Abundance, inadvertently exposes a blind spot in our collective moral calculus. In making their case for a better politics, I think they’ve also, as an accidental by-product, solved the infamous Trolley Problem.

Abundance argues that improving the supply of things like housing and energy is good on its own term and that material abundance can help address collective problems, like homelessness or climate change. The choice between allowing people to sleep on the streets in tents or forcing them into shelters is, as Klein and Thompson point out, a false dilemma caused by poor housing policy. The choice between growth and progress vs climate change is a false dilemma caused by poor energy and construction policy. Klein and Thompson are, justifiably, focused on the political thorniness of these issues, but, in their efforts, also demonstrate something startling: they implicitly demonstrate that material abundance can obviate moral quandaries.

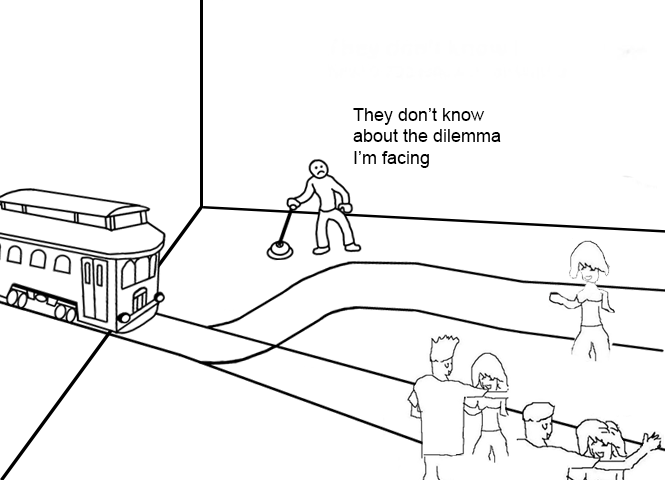

The Trolley Problem is so well known and over-explored it’s easy to forget that it is relatively new. The Trolley Problem is a modern moral dilemma. There are no trolleys in nature. You cannot replace the trolley with a bear or a hurricane or an opposing tribe—those things do not run on tracks, their brakes can’t go out, and there is no simple lever by which you choose their behavior. The Trolley Problem is a problem of technology, yet none of its solutions are allowed to be. Read more »