by Christopher Hall

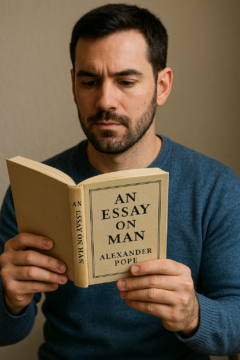

Despite writing my doctoral thesis on Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Man, a work most notorious for its poorly optimized optimism, I am something of a natural pessimist. Pessimism is at the right moments a potent tool for clarity (as is, even I have to admit, optimism, though not surprisingly I think this is the case more rarely), and so it is disappointing that the moment when I could have used it the most, my generally bleak perspective on things failed me. During my Masters, the professor who would eventually become my thesis advisor told me that, given the pathetic job prospects, a Ph.D. was not a good idea. Well, in your mid 20s, no obstacle, current or future, seems like it can become an indurated part of your fate if you choose for it not to. I was neither ambitious nor greedy, and I was willing to work anywhere for peanuts; so, the jobs would be there. Well, they weren’t, and in the midst of massive writer’s block and a crisis of faith concerning what literary criticism actually does, my prospects for an academic career tanked. I’m not sure if I can accurately say “I should have listened” as I am gainfully employed in a place where my degree is nominally required. But I don’t teach literature. And the writer’s block quickly metastasized into reader’s block; I still read, of course, but the urgency is gone (and the multiple distractions of the internet age are not helping.). Ah well, there are worse things, etc., and what does one want with being “well-read” anyway?

I suppose the actual question I’m wondering about is why I ever thought I could make being well-read a career. As the English degree craters, and the idea of the university itself is under assault in the United States and elsewhere, those of us who remain interested in literate culture are sensing in its decline some correlation with the current apoplexy, if not direct causation.

But I am allergic to any argument which is centered in the “use” of the humanities, at least if we understand “use” purely in the sense of “useful.” The disjunction between the “use” of the STEM disciplines and the “uselessness” of the humanities means that the world will stand study of the sexual habits of the pink fairy armadillo, not necessarily because it might lead to some new patent or product, but because it seems to be the price necessary to pay to keep science “going.” There can be no such argument for a study of sexual politics in Middlemarch. And the attempts to provide a “use argument” for the humanities have all, to my mind, fallen flat. “The humanities make you a good critical thinker;” is there any discipline out there that advocates for naivete among its practitioners? Hopefully there are not too many engineers out there taking everything they see at face value. “The humanities make people better democratic citizens;” well, if reading Rochester, Beckett, Byron and other assorted depressives and nihilists have made me a better citizen, I am not aware of how.

Conservatives – perhaps only the old sort of conservatives – may be fans of the “civic virtues” argument, while progressives want literature to help decompose the ideological structures they find in every corner of life. The issue, to my mind, with the moral use argument is simple: it demands that literature be about one set of things, when literature properly understood is about everything human (and a few non-human things as well, though always processed through a human perspective. Perhaps AI will change this.). This has also been my fundamental objection to the dominating focus of English faculties nearly everywhere; race, gender, and sexual identity are deeply important aspects of being human, but they hardly exhaust that experience. The objection will be that the politics of these matters demonstrate their foundational role in all human thought; “always politicize/historicize,” sure, but I wonder if I am the only one to think we are bound not to limit the subjects of literature. It concedes an important point to the enemy, because even if moral instruction, considered in the bluntest sense, is likely better generated elsewhere, it is a certainly that it is more digestible elsewhere. And that may be all that matters.

It may seem perverse to advance such objections at a moment when the lack of education seems a particularly dangerous form of social disease. Trump’s beloved poorly educated have now returned his affection two-fold, and the conclusion that a better-read country could never have voted for this conspicuous stupidity is deeply tempting, though hardly a sure thing. And I fully understand the impulse behind any form of “use” argument; we can’t very well just tell people we’re noodling around with novels and poems, can we? There’s public money at stake.

I don’t want to appear as if I am advocating a return to aestheticism. I rather think it is time we rethink the meaning of “use.” Our thinking about “use” makes it nearly analogous with “tool” – an object or process that makes things easier, that leads to a more efficient and positive outcome. We would never associate “tool” with something that made things more difficult – a wrench made out of soft rubber, for example. But there is, of course, tremendous “use” for things which do make things more difficult. Going back to critical thinking, which is oriented to clarify, we could perhaps rather say that the sort of thinking which criticism teaches exists precisely to make things more obscure, or, paradoxically, to see the obscurity in everything.

Let’s advance the Black Hole argument for the study of literature: we ought to study it because it is there and it is strange. We can go a little further; literature exists within the symbolic universe humans have created for themselves, but each individual work is a singularity, a hard knot of impossible matter, completely inscrutable at its centre, but subject nevertheless to multiple forms of investigation. The exact same can be said of human consciousness; I am deeply cautious about the current conversation concerning the idea that consciousness might be fundamental to the universe (one needs to very cautious about things one wants to be true) but the Hard Problem remains very relevant to the literary media which have proven to be the best representations of what it is like to have a mind.

I do admit to itching a bit when I hear someone saying we need to “problematize” something. We also need to get away from the idea that literature “enchants” while criticism “disenchants,” or any combination thereof. Kierkegaard, as he saw people buzzing about him making life easier, saw it as his mission to “create more difficulties.” We must occasionally render matters more esoteric than they appear. There are times when the world comes at us too clearly, and there is no denying that there is palpable pressure from the rest of society, and from the political realm, to see and state and praise the literalness of everything. The anti-tools which literature and the best criticism provide us with are opposed to this impulse.

I am not taking aim at those who find comfort in their favourite book, or feel they have found some truth within. It would take a hard – and determined – heart to keep at the study of literature and believe simultaneously that it was either meaningless or impenetrable to scrutiny. The symphony does not necessarily end when the chord resolves; each moment of clarity achieved from reading is hard-achieved, and never final, but this hardly means the clarity was false. Kant’s description of art as “purposiveness without purpose” perhaps best describes the motion of reading; we move forward and remain in the same place.

Every time I find an excuse not to read, not to finally pick up – insert the long, dense work of your choice, chances are pretty good I haven’t read it – I regret my participation in a world which seems to have lost its joy in obscurity. But I don’t want to sound like a cranky 19th century anti-utilitarian, as I think the matter is more serious than the instances of practiced frivolity we need to stay sane. Consciousness itself, I think, participates in this motionless motion. At any rate, the instrumentality of modernity is causing us to lose the capacity for a complex inner life. There is a reason we don’t use “simple-minded” as a form of praise.

There is another important element here; literary study must be associated with its own form of cognitive method that distinguishes it from anything in science, or any other discipline, really. This is another thing that has bugged me about the various defenses of the humanities and of English in particular; they all, in one way or another, seem to be pleading with the rest of the world to recognise that they too have a method which correlates in some way to something more “scientific.” While I cannot articulate precisely what this sort of thinking is – I’ve been trying to here, likely without much success, and will try harder in a future essay – I am convinced that literary study must set out its own terms of method. Science will always do science better, and the current models of “problematization,” while getting closer to the mark, still fail to convince because they seem so firm in the moral quality of their conclusions.

Humanities departments will, it seems, shrink to the size of vestigial organs which exist as reminders of some previous state of relevance. Universities, interested in keeping up appearances and thus not quite willing to abandon them entirely, will allow token English departments with two or three professors and maybe a hapless graduate student. But as I think of the mere act of reading more and more as an act of resistance, I wonder if this might be the time to re-center the study of literature, and literature itself, as an anti-tool. “Today we are going to make things more difficult,” we might say. “Perhaps we’ll start with An Essay on Man…”

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.