by Derek Neal

In the first round of this year’s NBA playoffs, Austin Reaves, an undrafted and little-known guard who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers, held the ball outside the three-point line. With under two minutes remaining, the score stood at 118-112 in the Lakers’ favor against the Memphis Grizzlies. Lebron James waited for the ball to his right. Instead of deferring to the star player, Reaves ignored James, drove into the lane, and hit a floating shot for his fifth field goal of the fourth quarter. He then turned around and yelled, “I’m him!”. The initial reaction one might have to this statement—“I’m him”—is a question: who are you? The phrase sounds strange to our ears. Who could you be but yourself? And if you are someone else, shouldn’t we know who this other person is? Who is the referent of the pronoun “him”? Perhaps because of its cryptic nature, “I’m him” is an evocative statement, and it has quickly spread throughout sports and gaming culture. In a 2022 episode of “The Shop,” Lebron James himself declared “I’m him.” On YouTube, there are numerous compilations with titles such as “NFL ‘I’m Him’ Moments.” If you search the phrase on Twitter, people use it in relation to sports, music, video games, and themselves. But what does it mean, and where did it come from?

In the first round of this year’s NBA playoffs, Austin Reaves, an undrafted and little-known guard who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers, held the ball outside the three-point line. With under two minutes remaining, the score stood at 118-112 in the Lakers’ favor against the Memphis Grizzlies. Lebron James waited for the ball to his right. Instead of deferring to the star player, Reaves ignored James, drove into the lane, and hit a floating shot for his fifth field goal of the fourth quarter. He then turned around and yelled, “I’m him!”. The initial reaction one might have to this statement—“I’m him”—is a question: who are you? The phrase sounds strange to our ears. Who could you be but yourself? And if you are someone else, shouldn’t we know who this other person is? Who is the referent of the pronoun “him”? Perhaps because of its cryptic nature, “I’m him” is an evocative statement, and it has quickly spread throughout sports and gaming culture. In a 2022 episode of “The Shop,” Lebron James himself declared “I’m him.” On YouTube, there are numerous compilations with titles such as “NFL ‘I’m Him’ Moments.” If you search the phrase on Twitter, people use it in relation to sports, music, video games, and themselves. But what does it mean, and where did it come from?

An internet search turns up a few articles explaining the history of this statement. Apparently, a rapper named Kevin Gates was the first to popularize the phrase when he titled his 2019 album, I’m Him. In this instance, “Him” acted as an acronym for “His Imperial Majesty.” We could then understand people saying, “I’m Him” to be saying something along the lines of “I’m the king.” This expression would function much like another sports saying, “the GOAT,” meaning “the greatest of all time.” But I think there is more to it than this. Since Gates used the term, no other examples have used “him” as an acronym. Read more »

Aqui Thami. Resisters, 2018.

Aqui Thami. Resisters, 2018. I can’t sing. Or so I always thought. A notorious karaoke warbler, I would sometimes pick a country tune, preferably Hank Williams, so that when my voice cracked, I could pretend I was yodeling. Then one night, I stepped up to the bar’s microphone and sang a Gordon Lightfoot song.

I can’t sing. Or so I always thought. A notorious karaoke warbler, I would sometimes pick a country tune, preferably Hank Williams, so that when my voice cracked, I could pretend I was yodeling. Then one night, I stepped up to the bar’s microphone and sang a Gordon Lightfoot song.

My father’s mother—Annie Newman, my grandmother or Bubbi—was born Hannah Dubin in a shtetl in what is now Ukraine a few years before the Great War. One of her earliest recollections—in addition to the image of her own grandmother hiding in a baby carriage to escape marauding Cossacks—was of being able to see troop movements from the roof of her house, presumably during the Russian Imperial Army’s advance against Austria-Hungary, an engagement that occurred in Galicia, farther to the west, in 1914. Much later, in the aftermath of the nuclear accident in Chernobyl in 1986, when that obscure place was suddenly on everyone’s lips, she began recalling that her village, which she called Priut, in a region she referred to by its Russian name as Екатеринославская губернія, or Yekaterinoslavskaya guberniya—the Yekaterinoslav Governorate, a province of the Russian Empire—was not far from that site, which had now become infamous for a catastrophic meltdown.

My father’s mother—Annie Newman, my grandmother or Bubbi—was born Hannah Dubin in a shtetl in what is now Ukraine a few years before the Great War. One of her earliest recollections—in addition to the image of her own grandmother hiding in a baby carriage to escape marauding Cossacks—was of being able to see troop movements from the roof of her house, presumably during the Russian Imperial Army’s advance against Austria-Hungary, an engagement that occurred in Galicia, farther to the west, in 1914. Much later, in the aftermath of the nuclear accident in Chernobyl in 1986, when that obscure place was suddenly on everyone’s lips, she began recalling that her village, which she called Priut, in a region she referred to by its Russian name as Екатеринославская губернія, or Yekaterinoslavskaya guberniya—the Yekaterinoslav Governorate, a province of the Russian Empire—was not far from that site, which had now become infamous for a catastrophic meltdown.  A dear friend of mine recently passed away unexpectedly. He had recommended I read Viktor Frankl’s

A dear friend of mine recently passed away unexpectedly. He had recommended I read Viktor Frankl’s

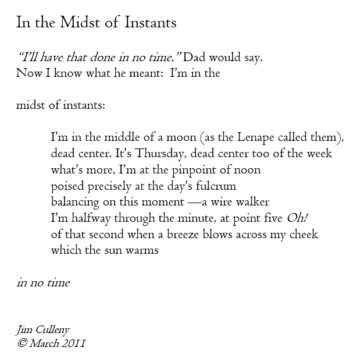

In the typical American city where we live, the average commute time is 78 minutes a day and 97.5% of

In the typical American city where we live, the average commute time is 78 minutes a day and 97.5% of  The

The

Every generation, when it reaches a certain age, makes two proclamations: Saturday Night Live used to be funnier, and “kids these days” are lazy and stupid.

Every generation, when it reaches a certain age, makes two proclamations: Saturday Night Live used to be funnier, and “kids these days” are lazy and stupid.