by R. Passov

Summer of ‘22

In a coffee shop a short train ride north of Manhattan along the Hudson River, there’s a vigil. A group, drawn from neighboring villages, is watching a someone slide to their end. Though long in the making, the apparentness is recent – severely distending belly, shrunken arms, swollen legs, gaunt face.

Basi, close to his real name, is a nickname sometimes used. There’s nothing special about him. He’s in his late 60’s with two grown children and well into a long-term suburban marriage, the kind where you stay while doing all you can to get away.

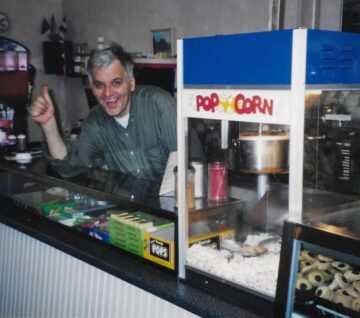

His first coffee shop was across the street from the shop in which he tends his last days. We come by. We sit, we order – double macchiatos in my case, espresso or cappuccinos for others. Basi sits with us, too infirm to move. Thankfully a nice young woman – Julene – patiently works the counter, handling orders along with critiques of her barrister shortcomings.

I’ve decided that Basi is not being mean when he criticizes Julene. Instead he’s treating her as though she’s in a privileged apprenticeship at a struggling Italian coffee shop you’d find on the outskirts of Rome, where Basi spent much of his youth. The kind more likely to be full in afternoons rather then mornings; full of day workers and doctors, lawyers and police officers, conmen and senators coming for their end of day espressos combined with enough bullshit to get them through the night.

That’s what Basi has built over these last 25 years.

***

We moved East not too long after Basi opened his first cafe. I’d bring my two young children on summer days for chocolate and hazelnut gelato like you could get nowhere else. It tastes richer Basi explained but it’s lighter in calories than other ice creams and so worth all of the extra-pennies to bear the freight from Italy.

He watched not just my children grow. He watched whole families form, break up and reform into parts civil only when they happen to meet at Basi’s. He watched me after my divorce. I’d come around, order a coffee and try to squeeze into a conversation. Usually I’d find the same group sitting around a table. Man-boys dressed, whether sweatsuit or suit, mostly in black.

Of course there’s a Joe in the gang. A Joe who can barely squeeze his charisma into that small cafe. If Joe is not on your side, that’s too bad. But if he is, well Joe’s the kinda’ guy that were you to casually say, “One day, I’d like to go to the moon,” he’d shoot back, “I know a guy…” And soon, you’d be on your way.

And a Big Tony and a Little Tony (who no longer comes around.) They, along with Joe, may have run card games out of AirBnB rentals. After being told the amount of cash that accumulated over a night, I asked, “How did you guys keep the place from getting robbed?”

“Double doors, and me,” said Big Tony.

Donny, along with John and Frankie, you might say is the gang leader. He hands out the cigars to go with the Johnny Walker Black. (No whiskey for me.) Yes, he was at Trump’s inauguration and, like most of the rest of the gang, he has his collection of MAGA views supported by the same fountain of ‘fair and balanced’ news that feeds so many others.

It took some cajoling and a final nod from Basi for me to be invited into the group. Once in I got to stay past 4:00 PM, when the open sign reversed, the Johnny Walker and Barolo bottles opened, and the cigars came out.

Basi enforced a code of conduct: Don’t be a jerk. It didn’t matter how you got to where you were or which direction you were headed. If you could manage the entry fee then you were welcomed into a club with folks you could know over just a few words. In front of whom every now and then you could drop something and it stayed right where you left it.

It helped that I know how to light and smoke a fine cigar. But I also served a purpose: the token democrat, first the Hillary voter and then the Biden supporter. While I smoked I listened to stories about being at the 2016 inauguration, as a ‘MAGA guest.’ And about second amendment rights and about how everyone is busting everyone’s…

I listened most Saturday’s. One double decaf macchiato until the sign was turned so that it read ‘Closed’ to passersby. But which really meant ‘Open to the cigar crowd.’ Once that signed turned, with one exception, whiskey, wine, cigars and talk flowed freely. The exception: Liberals are to be seen and not heard.

I listened and learned. Some of the gripes had legitimacy.

***

When Basi first showed signs of slowing, Donny, along with John and Frankie quietly built a safety net. Julene cleaned a restaurant owned by the gang leaders. They talked her into showing up to the cafe on most afternoons to suffer through Basi’s abuse while helping serve and clean.

“She comes in late, doesn’t have any clue what a day’s work is, then takes all the tips!” Basi complained over and over. But we’d say, “You need her. You do.” So, she stayed.

Basi passed in October of 2022. On a Sunday in the August before he passed I happened to find myself in the cafe, alone with Basi. He was sitting on one of the red leather benches, in a silent cry. “Basi,” I asked, “What’s wrong?”

He took his time to look up. “I’m crying for a friend.”

For a friend? I asked.

“Yes, for a friend who is dying.”

No words beyond that. I knew he was grieving his own, imminent, passing.

The restaurant owned by the fellas was held open on a Saturday. Several hundred showed for remembrances, along with an open menu and bar. It was a long, celebratory affair. A month or so after the wake, I wandered over to the coffee shop. Another slow Sunday. Julene and I were alone. I could see tears in her eyes. I invited her to sit and talk.

“I told Basi I was going back to Mexico. Leaving my two children (in their late teens) with my ex-husband. I just can’t take it anymore.”

No you’re not, Basi said. “I am retiring next year (likely he was already aware of his incurable cirrhosis). I’ve decided that you’re taking over. I will still come but only so that you can wait on me while I criticize how you make the espresso.”

Julene said she thought she was being pranked but something kept her on. Basi’s deterioration became apparent and though the criticism increased, so did the bond. They would sit out front on slow summer days and cry together, she because she hadn’t seen her parents in twenty years, he because he knew he was dying.

One day, almost a year after having first taken her aside Basi said, “In about a month this will be yours.” Julene offered that by the time she heard this she had let the original conversation slip away. A month passed. It was a Sunday. By then Basi could only sit and watch as Julene went through the process of closing the cafe. She helped Basi to his car, nervous that he still insisted on driving. He left while she had a few more steps to complete the closing.

Five minutes later he called, said he was on his way back and that she should wait for him. When he arrived he handed her the keys. “That’s it. It’s yours. Take good care.”

He drove himself to the hospital. Three weeks later, he passed.

Over the course of the prior year, Basi had worked with Donny, John and Frankie to arrange the transfer of the business to Julene. The cafe is open six days a week. Julene is there and, on most days, one or both of her children. The gang has stayed loyal, happy to let anyone know how Julene is an example of the American Way and how a vote for Trump will make America great again.