by Derek Neal

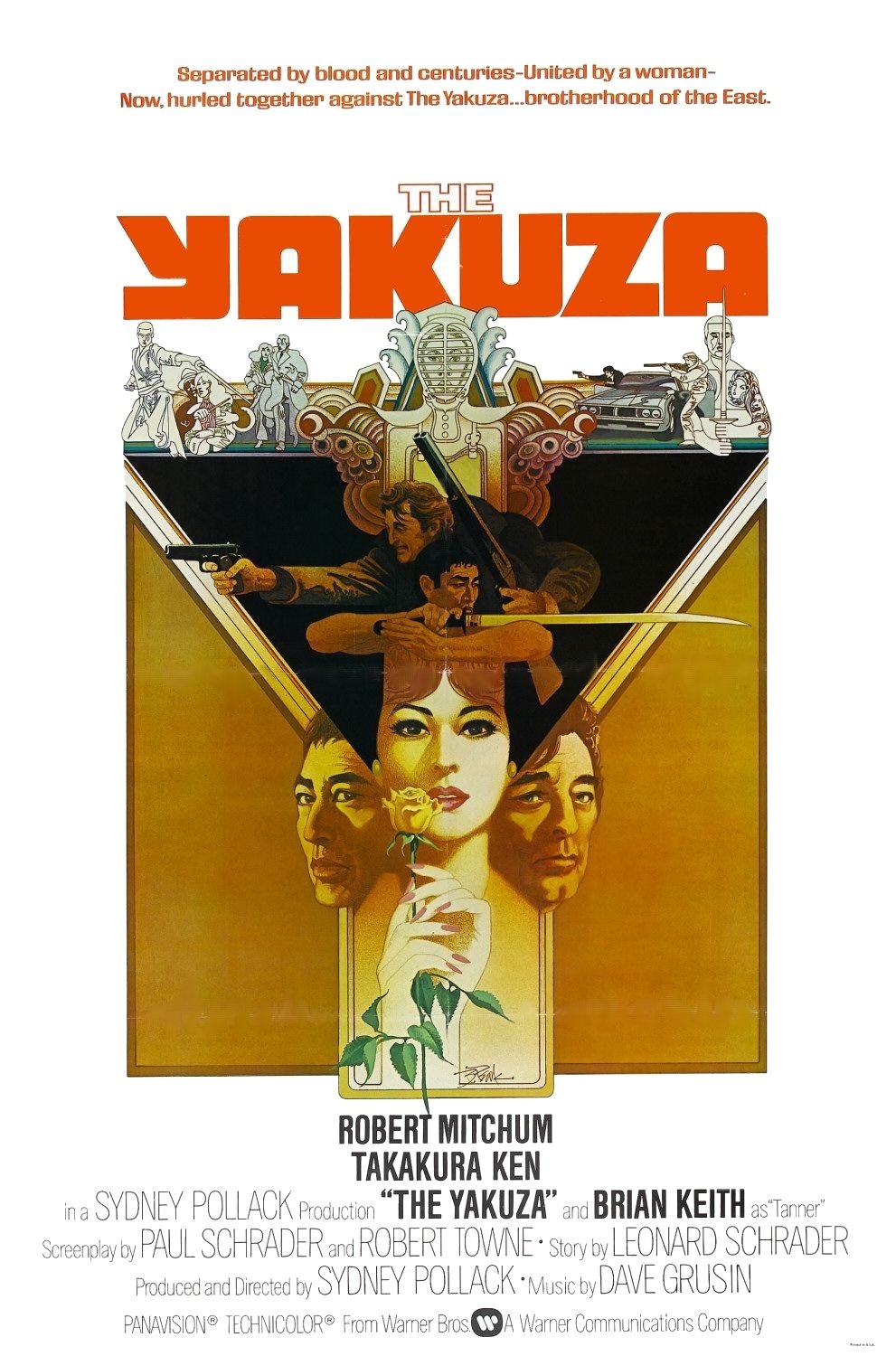

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza.

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza.

The Yakuza is a sort of Japanese film noir: an ageing American war veteran returns to Tokyo 20 years after leaving to do one last job, but events predictably spiral out of control until they threaten to consume him and everyone he cares about. Ultimately the film is about relationships and what one owes to others, and how this understanding is complicated by differing cultures and a modernizing world. In one scene, a young American named Dusty, the bodyguard of the protagonist, asks their Japanese partner to explain the concept of giri:

“This giri…” begins Dusty.

“Giri. Yes?” responds Tanaka Ken.

“It means ‘obligation,’ right?

“Burden.”

“Burden?” asks Dusty.

“It’s called ‘the burden hardest to bear,’” explains Ken.

“Yeah, well…suppose you don’t bear it?”

Tanaka Ken looks down, then takes a seat as he realizes Dusty does not understand the concept.

Dusty continues: “I mean, no one’s gonna come down on you.”

“No,” confirms Ken.

“Well, you guys believe in some kinda heaven or hell?”

“No,” repeats Ken.

Dusty shakes his head. “Then what is it that you believe in that makes you do it?” he asks incredulously.

“Giri,” responds Ken, nodding his head.

Dusty looks back at Ken, perplexed by this tautological explanation. How can giri make one do giri, he seems to be thinking.

“Don’t worry about that, Dusty,” says Ken, the implication being that a foreigner can’t understand giri.

Nostalghia is a film that is cheapened by summarizing it, but it is broadly about a Russian poet’s trip to Italy to research a Russian composer who had visited the same area. The protagonist, named Andrei, drifts around the town, ignores the female translator he is working with, and becomes fascinated with a local man named Domenico who is said to have locked his family away for seven years in an attempt to save them from his imagined end of the world. Eventually the police raided his home, freed his family, and now the man lives alone and attempts to traverse a thermal bath with a lit candle each day. However, he is unable to complete his task; the villagers repeatedly pull him out of the water thinking that he means to drown himself. As I said, it’s not worth summarizing the plot of Nostalghia, not because of any fault with the movie, but because the movie is so much more than the sum of its parts.

Nostalghia is a film that is cheapened by summarizing it, but it is broadly about a Russian poet’s trip to Italy to research a Russian composer who had visited the same area. The protagonist, named Andrei, drifts around the town, ignores the female translator he is working with, and becomes fascinated with a local man named Domenico who is said to have locked his family away for seven years in an attempt to save them from his imagined end of the world. Eventually the police raided his home, freed his family, and now the man lives alone and attempts to traverse a thermal bath with a lit candle each day. However, he is unable to complete his task; the villagers repeatedly pull him out of the water thinking that he means to drown himself. As I said, it’s not worth summarizing the plot of Nostalghia, not because of any fault with the movie, but because the movie is so much more than the sum of its parts.

At the beginning of the movie, Andrei and the translator, Eugenia, visit a church that is famous for its painting of a pregnant Madonna, the Madonna del Parto. It seems that the church is visited by women wishing to become pregnant, but Andrei and Eugenia simply go to see the painting. The sacristan of the church engages Eugenia in conversation:

“Do you want a child, too? Or forgiveness for not having them?” asks the sacristan.

“I’m just here to look,” says Eugenia, turning away and not wishing to be bothered.

The sacristan then turns to face the camera, speaking directly to the audience: “Unfortunately, when someone is distracted, and a stranger to prayer, nothing happens.”

Now Eugenia is interested. “What’s supposed to happen?” she asks.

“Whatever you want. Whatever you need…But at the very least you must kneel,” the sacristan tells her.

“No, I can’t do it,” she says.

“Look at how they do it,” says the sacristan, meaning the other women in the church.

“Them, they’re used to it.”

“They have faith.”

“Yes, maybe that’s it.”

As I watched this scene, I thought of Tanaka Ken’s explanation of giri. One bears one burden, performs one’s obligation, because that is what one does. By believing in this concept, it is made real. In the same way, to witness a miracle in the church, one must first believe that it is possible, then perform the required act that will bring it about. Eugenia must kneel, putting something else before her own self; in other words, she must take a leap of faith. She can’t do it.

After a short pause, Eugenia decides to ask the sacristan a question, much like Dusty asking Tanaka Ken to explain giri.

“Listen, I’d like to ask you something,” she says.

“Yes…?” replies the sacristan.

“In your opinion, why is it only women who pray so much?”

“And you’re asking me?” he wonders.

“Well, you must see a lot of women in here…” Eugenia explains.

“I’m just the sacristan, I don’t know about these things…”

“Ok, but maybe you’ve asked yourself sometimes why women are more devout than men.”

“Ah, you should know better than me,” the sacristan deflects.

“Because I’m a woman? Actually, I’ve never understood these things.”

The sacristan gives in, although he seems to know that Eugenia will not like his answer. “I’m just a simple man,” he begins, “but in my opinion, a woman’s purpose is to have children. To bring them up with patience and self-sacrifice.”

“And they have no other use, in your opinion?”

“I don’t know.”

“I understand. Thank you. You’ve been a great help,” she says hastily.

Flustered, the sacristan replies: “It was you who asked me what I thought. I really don’t know. You want to be happy, but there are more important things…”

Eugenia walks away. The sacristan calls out to her to wait, but she does not.

In the cinema where I saw Nostalghia, an informal discussion was held upon the conclusion of the film. This scene came up, and one person dismissed the sacristan as a “simpleton.” Then the discussion moved on to other topics. This person is correct, in a sense. The sacristan himself says that he is a simple man. But to me, this scene contains one of the most important ideas in the movie: we become what we are by believing in something outside of ourselves, and we find meaning in life through our relationships with other people. No one would accept the sacristan’s limited description of a woman today—and rightly so—but in the grander scheme of things, in the dichotomy between living for others and living for oneself, we sense that there is something the sacristan understands that Eugenia does not. “You want to be happy,” he says, “but there are more important things…”

I’ve begun my discussion of both films by focusing on a minor character who seeks to understand something they feel intuitively but cannot articulate in words. In both cases, these conversations, between one who knows and one who does not know, present the main drama of the film that will be acted out by the main character, Andrei in Nostalghia and Kilmer in The Yakuza.

Kilmer is referred to as a “strange stranger” because, while he is an American, he seems to have internalized a more Japanese code of ethics. At the same time, Japan is becoming more and more “Americanized.” In one scene, Kilmer looks out upon a skyscraper from a traditional Japanese minka; in another, Tanaka Ken is described as a “relic” because he still believes in giri, while others do not.

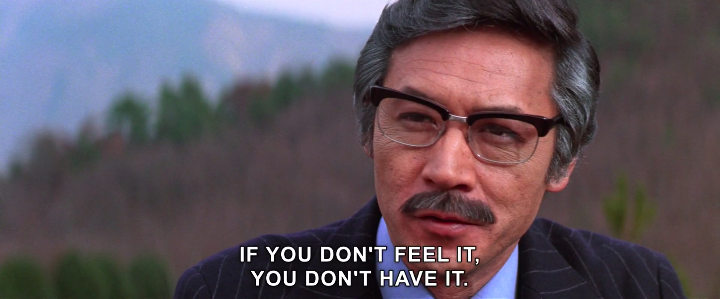

When Kilmer arrives in Japan, he calls on his old acquaintance Tanaka Ken to help him free the kidnapped daughter of his American friend, who has gotten mixed up in business dealings with a yakuza clan. Kilmer knows Ken will help him because he is duty bound to do so; he owes Kilmer a favor after Kilmer saved his sister in the war. But when things go sideways, Kilmer finds himself in the position of owing Ken a favor. Unless he intervenes, Ken will almost certainly be killed by the yakuza. When he is presented with this dilemma, he is told, “Whatever obligation you now have to Ken, Mr. Kilmer, if you don’t feel it, you don’t have it.” So does he have an obligation, or doesn’t he? That’s for him to decide. No one’s gonna come down on him if he walks away.

When Kilmer arrives in Japan, he calls on his old acquaintance Tanaka Ken to help him free the kidnapped daughter of his American friend, who has gotten mixed up in business dealings with a yakuza clan. Kilmer knows Ken will help him because he is duty bound to do so; he owes Kilmer a favor after Kilmer saved his sister in the war. But when things go sideways, Kilmer finds himself in the position of owing Ken a favor. Unless he intervenes, Ken will almost certainly be killed by the yakuza. When he is presented with this dilemma, he is told, “Whatever obligation you now have to Ken, Mr. Kilmer, if you don’t feel it, you don’t have it.” So does he have an obligation, or doesn’t he? That’s for him to decide. No one’s gonna come down on him if he walks away.

In Nostalghia, Andrei begins to develop a relationship with Domenico, the man who locked his family away. It seems that Andrei, too, may have abandoned his family; in any case, he feels that Domenico is a kindred spirit. Some may even wonder, as I did when watching the movie, if Domenico really exists, or if he is a figment of Andrei’s imagination, an external projection that is Andrei’s way of dealing with his past. This, however, is the wrong question to ask in a Tarkovsky film. Whatever the explanation is, Domenic asks Andrei to complete the task of carrying the lit candle across the thermal bath. Andrei agrees.

At the end of the movie, Andrei is preparing to return to Moscow when he receives a call from Eugenia. She is in Rome and tells him that she has seen Domenico, who is there for a protest.

“Domenico has asked about you many times,” she says. “He asked me if you’ve done everything you’re supposed to do.”

“Of course I’ve done it,” replies Andrei.

“Then I’ll go and tell him right away. He’s been waiting for this news.”

“Thanks.”

Andrei, however, is lying. He has not done what he must do. But must he carry the candle across the bath? No one’s gonna come down on him if he doesn’t. Domenico, it is clear, will never know one way or the other. Nevertheless, Andrei cancels his plane ticket home; he tells his driver to bring him to the thermal bath. Kilmer, too, decides to stay a little longer in Japan.

Both films end with their respective protagonists fulfilling what they see as their obligation. Kilmer helps Ken take down the enemy yakuza clan; Andrei carries the candle across the bath. This does not bring them happiness. In fact, they willingly suffer in order to complete what they see as their duty, their giri. If they do not, they know they will die a spiritual death. In Sculpting in Time, Tarkovsky’s book explaining his understanding of cinema, he writes:

Both films end with their respective protagonists fulfilling what they see as their obligation. Kilmer helps Ken take down the enemy yakuza clan; Andrei carries the candle across the bath. This does not bring them happiness. In fact, they willingly suffer in order to complete what they see as their duty, their giri. If they do not, they know they will die a spiritual death. In Sculpting in Time, Tarkovsky’s book explaining his understanding of cinema, he writes:

“Modern man in his struggle for freedom demands personal liberation in the sense of license for the individual to do anything he wants. But that is an illusion of freedom, and man will only be heading for disenchantment if he purses it.”

When reading this, how can we not think of the sacristan: “You want to be happy, but there are more important things…” Eugenia, when she calls Andrei at the end of the movie, updates him on her life as well as telling him about Domenico. She says she’s found a man, that he’s part of a prominent family, and that they’re leaving for India soon. She seems to have found what she’s looking for, but the images on the screen reveal her true state: she does not seem happy, but rather disenchanted. Tarkovsky continues explaining his understanding of cinema, or rather his understanding of life:

“The one issue that has to be raised, it seems to me, is the question of a man’s personal responsibility, and his willingness for sacrifice, without which he ceases to be a spiritual being in any real sense…I mean the spirit of sacrifice which is expressed in the voluntary service of others, taken on naturally as the only viable form of existence.”

Is this not giri? When Dusty decides to protect Kilmer, when Kilmer decides to save Tanaka Ken, and when Andrei decides to delay his return home—what he has been longing for the entire film—to perform an objectively meaningless act, they are voluntarily acting in the service of others.

When the screening of Nostalghia ended, the first question that was posed was about the meaning of rain and water in the film. My hand shot up. As it happened, I had been reading Sculpting in Time that very day and had read Tarkovsky’s explanation of rain completely by chance. He notes how people are always looking for symbols in his movies, but that his movies feature rain and water so much because this is characteristic of the environment in which he grew up. Tarkovsky even chastises the audience: “It seems that the cinema-goer has so lost the capacity simply to surrender to an immediate, emotional aesthetic impression, that he instantly has to check himself, and ask: ‘Why? What for? What’s the point?’” I felt a little bad about doing it, but I paraphrased Tarkovsky to the entire cinema, effectively telling the presenter that his question was irrelevant. Hey, they weren’t my words, they were his, the guy who made the movie!

The discussion continued without ever really getting to the heart of the film. This is understandable, however. To attempt to explain Tarkovsky’s movies is a futile task because it is, in effect, an attempt to translate images into words. In Nostalghia, Andrei says that “all art is untranslatable,” and I think that this is what he means. Form and content are inseparable, yet we try anyhow, inevitably. What does the candle that Andrei carries mean? What does the fire symbolize? Why must he cross the bath? Outside of the film, it means nothing; inside of the film, it means everything. As I left the cinema, a feeling of dissatisfaction permeated my body. We had not talked about what truly mattered, I felt. Had we sat through the movie, only to understand nothing at all? Was all art untranslatable? I went out into the cold night. In front of me, I heard a voice:

“No one even brought up Domenico” it said.

Before I knew what I was doing, completely out of character for me, but compelled by a force beyond my control, I responded: “I know! That’s what I thought, too!”

The figures in front of me turned around, surprised. They were two older women. The three of us, perhaps, sensed a current of understanding among us. “Everyone was talking nonsense, instead,” one of the women grumbled. I hoped she wasn’t talking about me, but again, those had been Tarkovsky’s words, not mine. We began to discuss the film, wondering about the relationship between Domenico and Andrei, the dream sequences in the film, the atmosphere of fog and rain permeating the screen. Eventually the cold dispersed us. We never talked about giri, or if performing one’s obligations is what makes a person a person. Maybe that cannot be talked about; maybe, that is what art is for.