by Barbara Fischkin

I arrived in Ireland in the mid-1980s to cover the seemingly intractable bloody conflict colloquially known as “The Troubles.” I studied up on materiel: Armalite rifles, homemade fertilizer bombs, the plastic bullets protestors ducked. And on the glossary of local politics: Loyalists were mostly Protestants who wanted to remain British citizens; Republicans were mostly Catholics who yearned for a united Irish nation. I interviewed people on both sides of the conflict but more women than men. I wanted to make their voices heard in the United States.

I was taken by one issue that had already created international headlines—the strip searches of female political prisoners.

But the stories I read did not quote the women who were being strip searched. They quoted politicians and sociologists instead of the women themselves. The stories said the policy was routine, part of the process of getting inmates out of civilian clothes and into prisoner uniforms. Not true. This was actually a well-conceived British military psychological operation to humiliate the women, a technique intended to “break” the women.

I decided that the only way to write about this was to getting inside the 100-year-old stone walls of Her Majesty’s Prison Armagh—and to talk to the women directly.

But to get in, even to speak to only one woman, I had to lie. I could not say I was a reporter. I had to say I was a cousin, visiting from the states. The Northern Ireland Office, run by dutiful Protestant colonists controlled by the British, kept the press out. Perpetrators of abuse do not like publicity. Now, as St. Patrick’s Day approaches, and two larger wars rage—wars that unlike the one in Ireland threaten us all—my mind keeps racing back to what is better known as “Armagh Jail.” Read more »

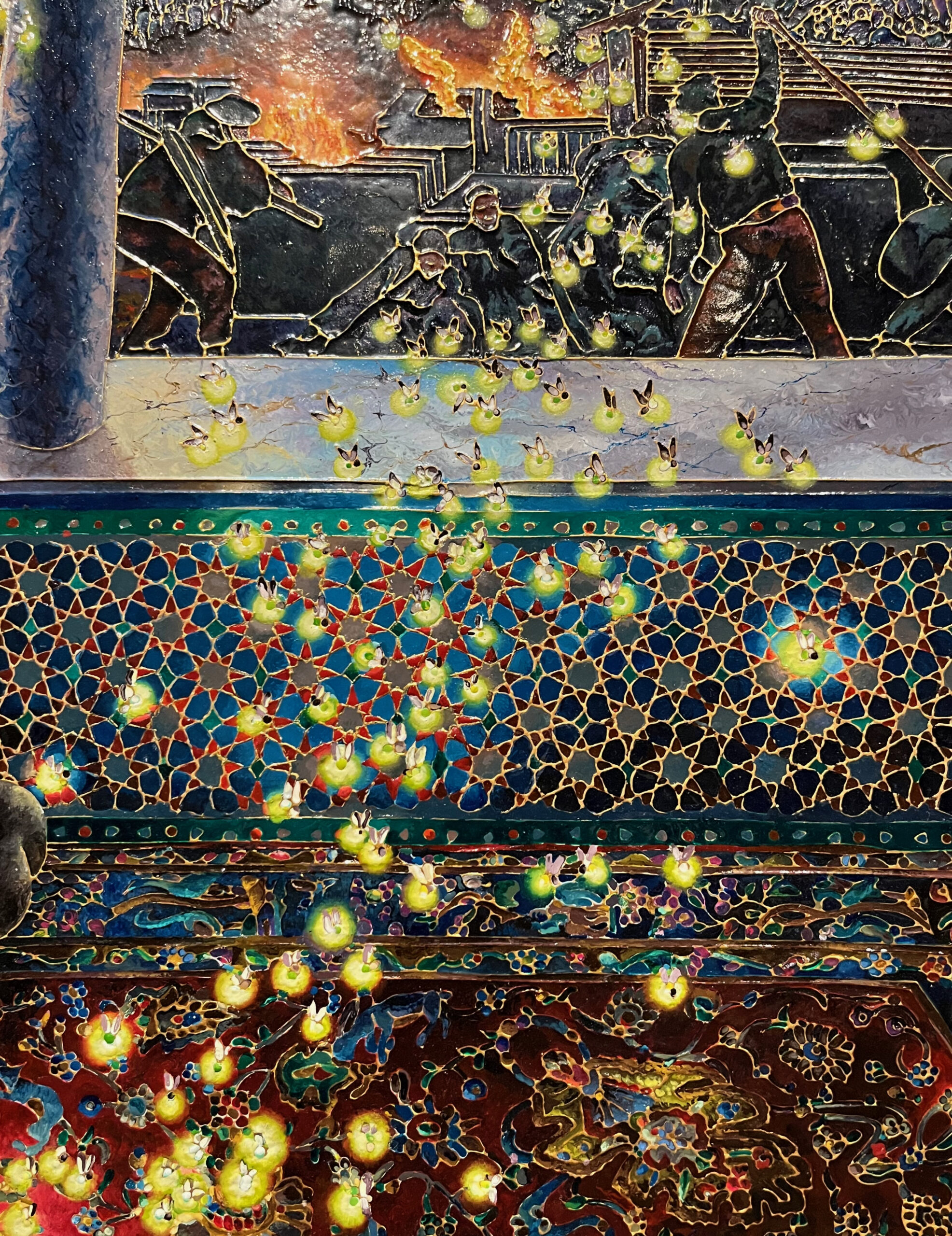

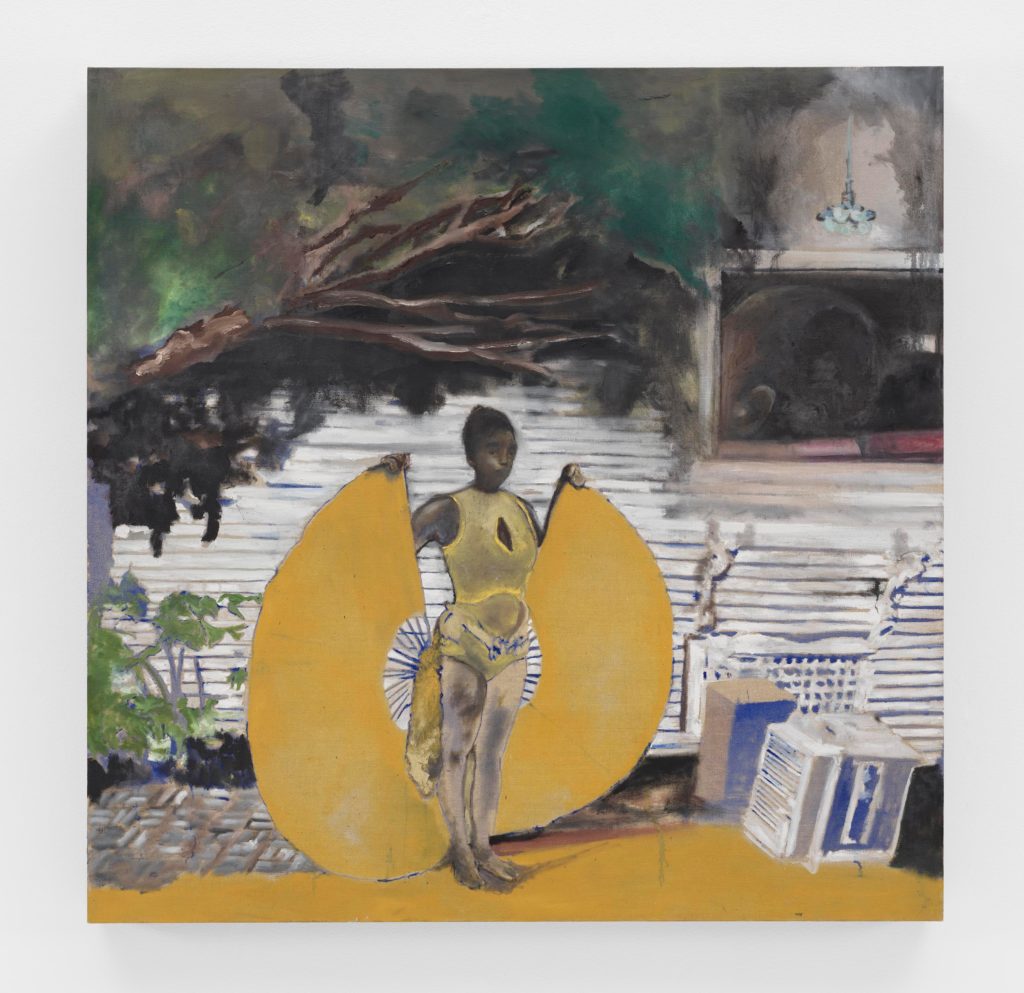

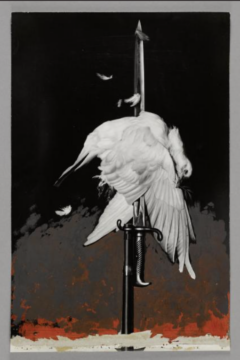

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)

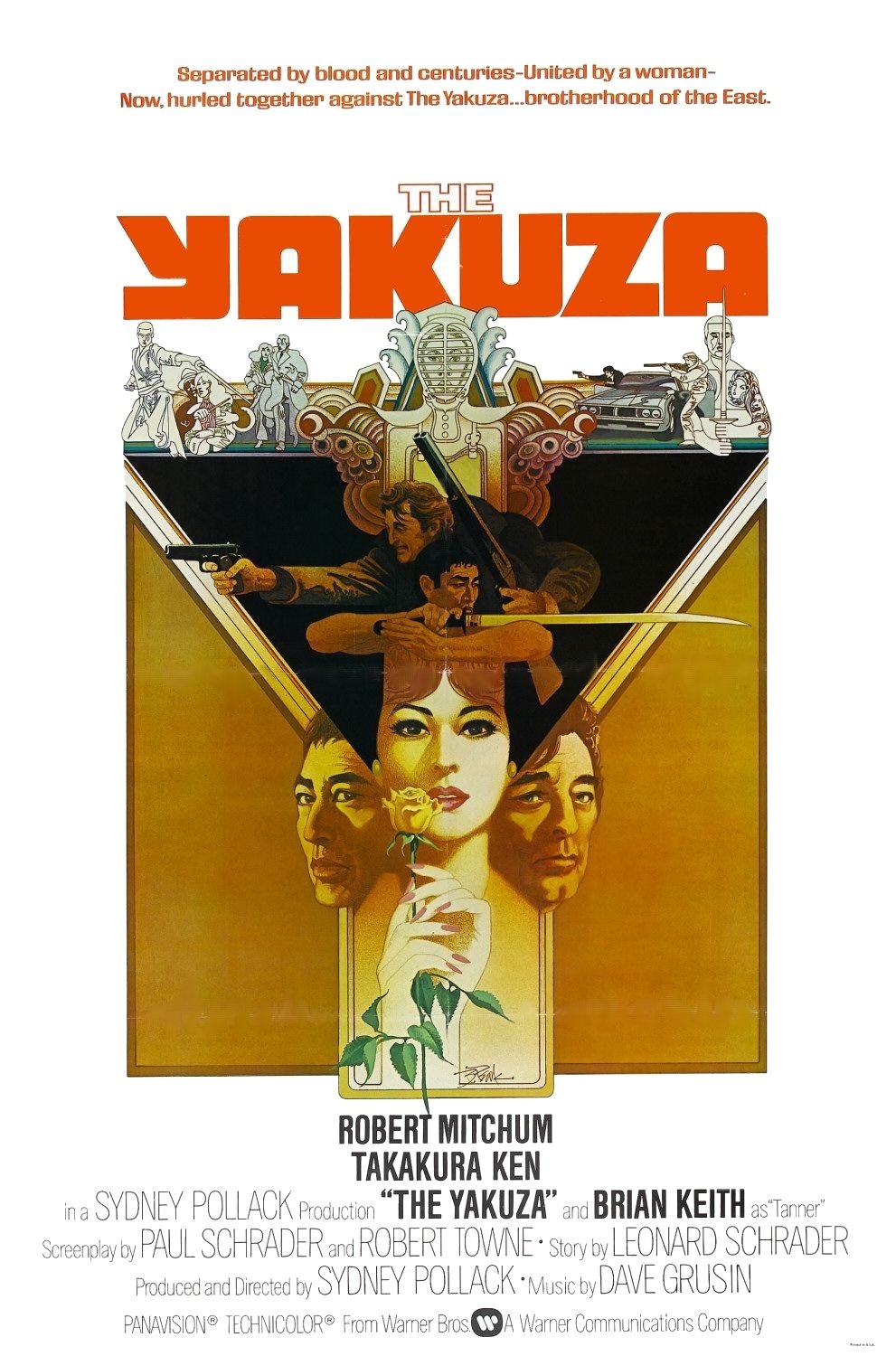

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza.

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza. A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released

A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released

Noah Davis. Isis, 2009.

Noah Davis. Isis, 2009.

What do we know about vampires?

What do we know about vampires?