by Philip Graham

For over twenty years I have been in awe of David Jauss as a writer, as a colleague and teacher, and above all for his insight into the contradictory human heart. His short stories have been gathered together in two essential collections, Glossolalia and Nice People, and many of these stories, I believe, take their rightful place among the best short fictions in American literature. He is a master of the precise, illuminating moment, and the clarity of his prose is deepened by his parallel work as a poet.

For over twenty years I have been in awe of David Jauss as a writer, as a colleague and teacher, and above all for his insight into the contradictory human heart. His short stories have been gathered together in two essential collections, Glossolalia and Nice People, and many of these stories, I believe, take their rightful place among the best short fictions in American literature. He is a master of the precise, illuminating moment, and the clarity of his prose is deepened by his parallel work as a poet.

It’s not surprising that his poetry collections, Improvising Rivers and You Are Not Here, are, in turn, informed by his work as a fiction writer. Jauss’s poems aren’t afraid of the tug of narrative. And because of his love of music, particularly jazz, he is more attuned than most writers to the importance of rhythm, unexpected harmonies, and structural invention in writing, whether prose or poetry.

Jauss is also the author of two important collections of craft essays, Alone with All that Could Happen, and, most recently, Words Made Flesh. David and I were colleagues for ten years at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, and I remember quickly learning to attend his craft lectures. David knew how to see through the common clichés of creative writing advice, whether it might be the accepted modes of characterization, the “flow” of prose rhythm, use of epiphanies in short fiction, or constricting notions of what constitutes a plot. The audiences for his lectures were always filled with both students and fellow faculty members because we knew that, when David spoke, we would all become his apprentices, and happily so. Read more »

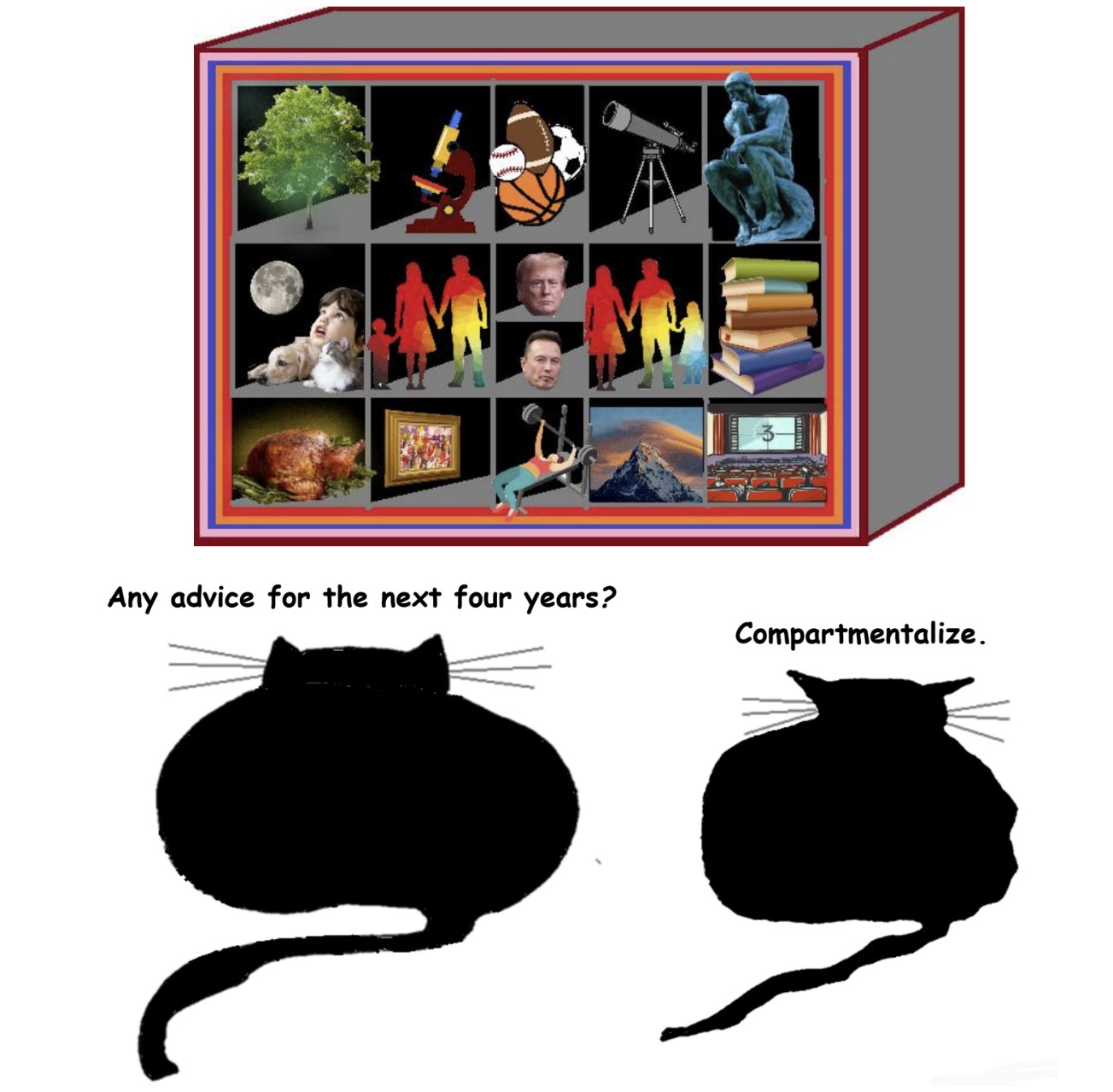

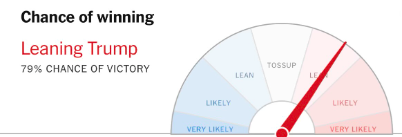

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election.

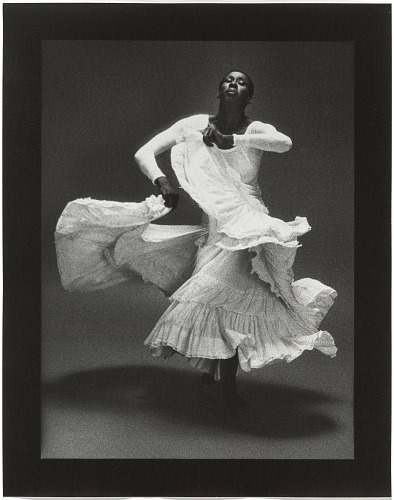

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election. Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.

Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.

I dipped my toe into

I dipped my toe into  Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

by William Benzon

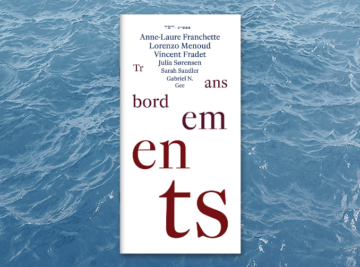

by William Benzon Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.