by Rebecca Baumgartner

I’m trying to read Walden. I also own a phone that gives me instantaneous access to the internet. These two things seem fundamentally at odds.

Whether our phone usage is a literal addiction that operates on the brain in the same way that alcohol and other addictive substances do, or whether the term “addiction” in this case is merely a metaphor, reasonable people agree that there is a problem with the way we use our phones.

To own a smartphone is to look at a smartphone – a lot, often to the detriment of our happiness, productivity, relationships, social skills, and awareness of the world around us (both in the mundane yet potentially deadly “Hey, the light turned green” sort of way and the abstract “Look at that beautiful cloud” sort of way).

Most of us are worried about, frustrated about, and/or ashamed of who we become when our phones are in our hands. Obviously, this is not true of all smartphone users, but it is true enough, for enough people, that we should take heed of the insight underlying the generalization.

While I haven’t fallen into the pit of Devil’s Snare that is Instagram or TikTok (or whatever the coolest data harvesting app is right now), I don’t consider myself at all virtuous when it comes to how I use my phone. This is because I let it consistently keep me from doing the things I truly love – first and foremost among them, reading.

It’s not just that having a phone always at hand ruins my concentration and makes reading more difficult. It does that, for sure. But it’s also that having a tiny portal to the internet a few inches away makes particular types of reading even more difficult. If a book demands a level of engagement that seems deliberately calculated to drive a 2025 reader insane – as Walden does – it comes to seem philosophically impossible, or at least unreasonably hard, to make your way through it when your phone remains a viable option for your attention. As it always is. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Approaching Washington, November 2024.

Sughra Raza. Approaching Washington, November 2024.

Oops. During most of 2024, all the talk was of deep learning hitting a wall. There were secret rumors coming out of OpenAI and Anthropic that their

Oops. During most of 2024, all the talk was of deep learning hitting a wall. There were secret rumors coming out of OpenAI and Anthropic that their

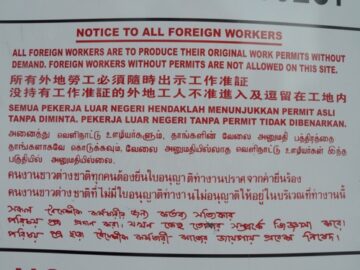

My great-grandparents were among the 12 million immigrants who passed through Ellis Island and equally a part of the wave of 20 million immigrants who entered the United States between 1880 and 1920. America’s fast-growing economy needed more manpower than its existing population had available, and the poorer classes of Europe were the beneficiaries including four million Italians (largely southern) and two million Jews.

My great-grandparents were among the 12 million immigrants who passed through Ellis Island and equally a part of the wave of 20 million immigrants who entered the United States between 1880 and 1920. America’s fast-growing economy needed more manpower than its existing population had available, and the poorer classes of Europe were the beneficiaries including four million Italians (largely southern) and two million Jews.

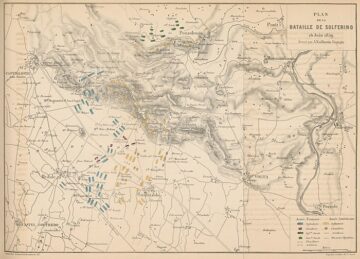

An empire, threatened on its flank, vents spleen

An empire, threatened on its flank, vents spleen

Some people use religion to get their life together. Good for them. I’m all for it. Although I myself am an atheist, I don’t think it much matters how someone gets their life together so long as they do.

Some people use religion to get their life together. Good for them. I’m all for it. Although I myself am an atheist, I don’t think it much matters how someone gets their life together so long as they do.

On the one hand, nothing has changed since August 2020, when I wrote

On the one hand, nothing has changed since August 2020, when I wrote

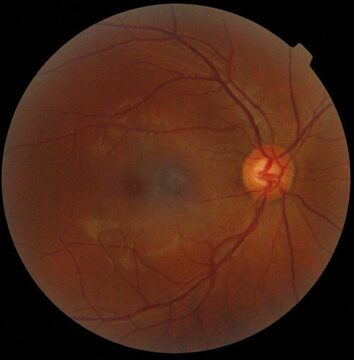

Anatomically, it’s the optic disc – the spot on each retina where neurons with news from all the light-sensitive rods and cones of the retina converge into the optic nerves. The optic disc itself,

Anatomically, it’s the optic disc – the spot on each retina where neurons with news from all the light-sensitive rods and cones of the retina converge into the optic nerves. The optic disc itself,

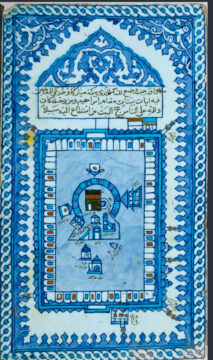

Sughra Raza. Rorschach Landscape, Guilin, China, January 2020.

Sughra Raza. Rorschach Landscape, Guilin, China, January 2020.