by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

You arrive in Makkah, a stranger. The skyline, a hotel-scape, all cold commerce, won’t let you forget it. But aren’t you here to come closest to your heart, finally, to behold the Ka’ba whose cosmic coordinates you would easily recognize, even with eyes closed, led by a primordial longing? Your eyes are closed this instance as you walk towards it; you are sublimely solitary and sublimely inseparable, conjoined with every manifestation of reality, all at once. The crowds around you are immense, as is the crowding of your consciousness, a jostling in every dimension. It takes some work to access the Makkah of the heart. There is an escalator and a few stairs you must descend, and yes, there is a hand to hold as you step down with your eyes closed. You are grateful for this hand, a new hand, but it belongs to no stranger. You trust your newly found teacher S. Sadiyya’s hand the way you earlier trusted S. Hamza’s words about sighting the Ka’ba with the energy of prayer alone at first, eyes shut. There is a verse by the poet Hafez e Shirazi about dipping your prayer rug in wine if your teacher says so, but you, educated in the West, accustomed to calibrating cultural distances, have not come to trust teachers without question. These teachers, however, share the culture of your very heart, guided and guiding with both ilm (knowledge) and ishq (love) in beautifully balanced measures.

What you are about to witness with your eyes for the first time, is the magnet whose force was your first turning as a newborn in your father’s arms when he made the Adhan/Azaan in your ear, also the direction you turned, or sought to turn to five times a day, every day. Today you embody that compass. Labbayk, “Here I am,” the compass says, “I answer your call.” When you open your eyes, the Ka’ba appears as magnificence and mercy, a simple cube structure covered in hand-embroidered black silken cloth; the words that appear on it are more than two-dimensional letters, they carry Divine revelation, “ayaat,” signifying each realm of creation. You are one among hundreds of thousands of roving bodies at any given time here, but you feel the outward stirrings cease. For a moment the air becomes cool and there is a palpable stillness and silence; could it be a breath of “Sakinah,” the quality of peace holding both tranquility and habitation— the peace you enter as an abode, “Maskan,” the peace that envelops every fiber of your being. It feels, without doubt, like your first homecoming. All other homes and arrivals were illusions.

The first calls to prayer made from the noble sanctuary itself flood you with emotion; you recall the calls past, every day, every season, at times live from a nearby mosque, mostly a recorded voice under the roof of your exile. You have brought a collective ache here; the ache of a dispossessed people, haunted by war, genocide, displacement. You, who are all ache, are now becoming all prayer.

Nights melt into mornings here, with hours for once ours; the call is the only clock that matters. It is your first morning now; you are in your “ihraam,” the sacred state of bodily and spiritual purification in preparation for the imminent Umrah. You have cleansed your body and covered it carefully, you have cleansed your heart of anger, bitterness, despair, even your greeting of salam, peace, feels more intentional as you meet with your group of fellow-pilgrims for a teaching before the Umrah. S. Omid’s words are a teacher’s amanah, trust; they are urgent and gentle, they come as some of the key reminders from the tradition, for this is the moment of locking into the spirit of faith with your deepest attention.

Deepest spiritual attention must be balanced with outward grace; the Ka’bah is no monastery, but a great field of fervent devotion, the Earth’s great singing bowl where the frequencies amplify the heart’s most ancient yearning, and the hearts within ihraam here are in the tens of thousands. The teacher, S. Omid’s voice and words channel the mercy that your faith promises, reminding to balance passion with Adab, finest manners. As you navigate through the crowds, you remember the Prophetic saying: “The only reason I have been sent is to perfect good manners.” (Al Bukhari). The present crush is a test of Adab in the face of riling impatience. The quintessential principle of sacred space is that it belongs to everyone equally.

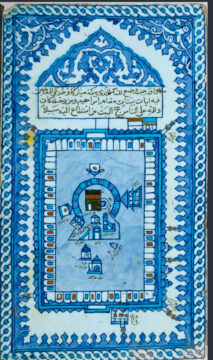

The Umrah begins with Tawaf or circumambulation– walking around the Ka’ba seven times, counterclockwise, so your heart remains nearest to it, as if you are a beam radiating towards it, or from it. Led by S. Owais, each revolution feels unique: a different prayer on the tongue, a different face in your peripheral vision, the sky, a subtly changed color. You are part of a great swirling, having joined the celestial rhythm. The Ka’ba, built of stone and clay, built by human hands, and rebuilt many times, most significantly by the Prophet Ibrahim and his son Isma’il—is an earthly alignment of the heavenly Ka’ba known as “Bayt ul-Ma’mur,” the true center of the cosmos, ceaselessly circled by angels.

Motion feels strangely intuitive here. The initial entry into Tawaaf is the kind of pull you have only imagined, likely when watching scenes of masses in outer space arranged into orbit by gravitational force. You now follow an orbit designed only for you in the vastest collection of orbits. Here is where hearts of the faithful are in unison; in Ibn e Arabi ‘s words: “When God created your body, He placed within it a Ka‘ba, which is your heart. He made this temple of the heart the noblest of houses in the person of faith. He informed us that the heavens… and the earth, in which there is the Ka‘ba, do not encompass Him and are too confined for Him, but He is encompassed by this heart in the constitution of the believing human. What is meant here by “encompassing” is knowledge of God.” (Futuhat ch. 355).

Before you begin Tawaaf, dawn is breaking. The softly changing light offers its own praise, as you are about to circle your truest, deepest desire, harmonizing with the praise-energy of the universe. As your pilgrimage progresses from Makkah to Medina, you find that the hearts that accompany you carry light in abundance, with the Almighty’s grace: S. Ali Keeler, whose voice and spirit has inspired you for many years, will recite the “verse of the lamp,” most cherished lines from Surah Nur, the Quran’s chapter “Light,” in his gifted voice, brilliant scholar, and soul-sister Seemi Ghazi will offer praise-songs for the prophet in many languages, one in particular, will capture the fragrance of love from the land of your birth to the land of God’s Beloved in the profoundest of ways.

***

This the first in a series of essays about the recent Umrah pilgrimage I took with the esteemed scholar and teacher of Sufism Omid Safi and fellow-scholars and teachers Sayyidah Sadiyya, Sidi Hamza Weinman, and Sidi Owais Mohyuddin. More essays on our time in Mecca and Medina are forthcoming.