by Marie Snyder

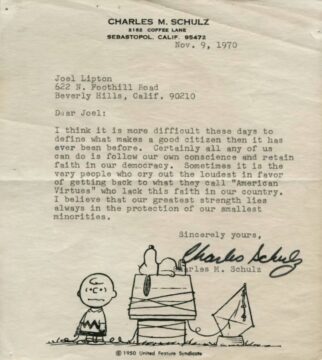

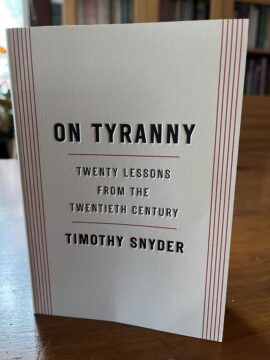

Timothy Snyder’s dictum, “Do Not Obey in Advance,” seems to be everywhere these days. It’s the title of the first chapter of his book out in 2017: On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, which is worth a revisit along with conformity experiments that back up his concerns and some clarification from a recent podcast.

When I first read this book seven years ago, it seemed like a concern for a far off future that would surely not happen in my lifetime. But it has lately reemerged as a prescient warning, and now there are more obvious signs that we need a path through potential political ruptures. In the first few pages, Mr. Snyder points out the power we have in avoiding acceptance of tyranny and the danger we fall into if we do obey:

“After the German elections of 1932, which permitted Adolf Hitler to form a government, or the Czechoslovak elections of 1946, where communists were victorious, the next crucial step was anticipatory obedience. Because enough people in both cases voluntarily extended their services to the new leaders, Nazis and communists alike realized that they could move quickly toward a full regime change. The first heedless acts of conformity could not then be reversed. …As the political theorist Hannah Arendt remembered, ‘when German troops invaded the country and Gentile neighbors started riots at Jewish homes, Austrian Jews began to commit suicide.'”

It’s the mere act of going along that could determine if we lose another mass of people in heinous ways, divided apart from among us in one way or another. We’re seeing that unnerving agreement already in some political speeches and pretty mainstream news outlets.

Mr. Snyder writes about Stanley Milgram’s attempts to “show that there was a particular authoritarian personality that explained why Germans behaved as they had” with his shock experiments conducted on hundreds of people. Instead, when most of his participants shocked another person until their perceived death, “Milgram grasped that people are remarkably receptive to new rules in a new setting. They are surprisingly willing to harm and kill others in the service of some new purpose if they are so instructed by a new authority.”

This experiment was one of many that came after WWII to try to figure out what could possibly have compelled regular people to participate in the rounding up and gassing of millions of people. Hitler couldn’t have done all that on his own, but he was able to sway the masses to join in. We need to be aware of this stark reality to ensure we, ourselves, don’t end up passively agreeing to harm others or allow harm to come to others.

The Experiments

I used to teach these studies to high school students with an assignment attached to break a norm. Often it’s perfectly fine to blindly follow rules and guidelines, but sometimes, every once in a while, it can permit atrocities to happen: from cruel conspiracies against that one person in your friend group who’s a little different all the way up the scale to genocidal actions. So it’s absolutely vital to be able to think about the norms we follow, and, from time to time, to break the less useful ones just to make sure we still can. We need to practice non-conformity to make sure we can do it when we need to. It’s always wise to take a minute to think, ‘Do I really agree with this, and could it harm anyone?’ before acting.

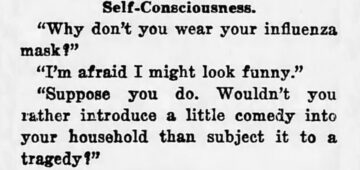

In 1951 Solomon Asch had one participant and a group of confederates (who were in on it) state which is the longest line in a series, but the confederates all said the same wrong line for a few responses to see what the lone participant would do. Almost 40% also said the obviously wrong line was correct. When a majority does something, even when it’s blatantly inaccurate, it tends to make us question ourselves. Following along can help us avoid the discomfort of making waves, especially in a meaningless experiment we’re just doing for some quick cash (video here). We can see this today in the discomfort of people who want to wear a mask to protect themselves or others but can’t bring themselves to do it. It’s hard to be different.

Then came Milgram’s experiments in which two people did a rigged coin toss that would always make a confederate (an actor) get the part of the test taker and the participant the test-giver. The test-taker had to memorize a string of words and would get a shock after any error, with the voltage increasing with each mistake. At a specific point, the actor would mention his heart condition and later keel over. The observing experimenter would just say, repeatedly, ‘Please continue with the experiment.’ As you can imagine, it was extremely distressing for the participants, yet 63% continued to shock the confederate to the maximum level (video here).

In 1963, Hannah Arendt’s famous work, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil came out. The Jewish German writer escaped a prison camp during the war and made it to the U.S., then was convinced by the New Yorker to return during the war crime trial of Adolph Eichmann. Like Milgram’s realization, her stance was that Eichmann wasn’t a monster, but just a regular person following the rules. A massive backlash ensued against the possibility that there could be people like that among us – that we could ever be like that. It’s not unlike early arguments, quickly dispelled, against the possibility that 51 regular, ordinary men could sexually assault Gisèle Pelicot, who announced to any victim of sexual violence, “Look around you: You are not alone.” We want to believe these things could only be done by deviants, yet recently the The Telegraph uncovered a “rape chat group” with over 70,000 members. Arendt turned her article into a book explaining how easily and successfully a bureaucracy can create a populace who will do anything if they’re divorced from any sense of personal responsibility and eager to do a ‘good’ job for the authority figures directly rewarding them. We have to pay attention to the types of bureaucratic institutions that are just following the rules when the circular nature of bureaucracies create a rule by nobody. And we have to develop and keep in touch with our own values.

Then, in 1968, reacting to MLK’s death, Jane Elliott did her famous blue eye / brown eye experiment on her grade 3 students, giving one group arm bands based on something as innocuous as eye colour, and merely suggesting they were kind of dumb and not very clean as she moved their seats to the back of the classroom. That was enough for the other half of the kids to hate and bully them. She undid their hatred the next day by pointing out what she had done in order to teach the children how easily people can slip into seeing others as enemies with the smallest suggestion (video here). This is an important lesson to remember right now. Is that person who’s being dismissed or ridiculed any less deserving of the dignity and safety you expect for yourself because of a difference in a detail or two?

Then, in 1968, Latané and Darley ran the Smoke Filled Room experiment in which a participant is placed in a room that appears to be filling with smoke from a fire. If alone, the participant immediately got up to tell the researchers and left for safety. However, when there were confederates in the room who didn’t react, the participant didn’t react either for at least 20 minutes (video here).

Essentially, we’d rather die and/or enable harm to others or ourselves than look weird.

Zimbardo rounded it all off in 1971 with the famous Stanford Prison Experiment that pitted student volunteers against one another by randomly assigning them to play the part of either prisoners or guards. The guards got power-hungry and abusive, and some prisoners defaulted to passive subservience.

Social cohesion is vitally important to our survival, so it makes sense to follow the herd except when it’s running off a cliff. Then we need to use our prefrontal cortex to think about the wisdom of their decisions and whether or not we should forge a different path. But the most important thing to remember is that, in every single one of these experiments, there were people who didn’t blindly follow the crowd or the instructions and instead questioned them or just walked out. A good 10-30%, and sometimes 60%, of people rejected the pull towards obedience in favour of doing the right thing.

The Podcast

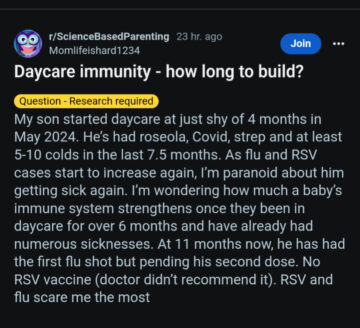

Recently, Timothy Snyder spoke with Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush about his new book On Freedom and what it looks like to obey in advance. Mr. Snyder explained that, to avoid being led into a tyranny, we have to know ourselves and develop a solid sense of what’s right and what normal means. We saw with Covid how quickly normal devolved into meaning getting sick several times each year.

Mr. Snyder suggests writing a letter to yourself about what’s important right now, and then check it frequently to see if you’re changing. “Even if you’re a saint, you’ll feel that tug to go along with the tide and obey in advance.” We need to talk about this with other people and check in with them again and again. “People will adapt and not notice.” And it’s important to do all this. “The only way Trump transforms the system is if people think he can and focus on how to protect themselves gives him the power. Once you’ve done that, you’ll use the rest of your mind to justify having done it. The usefulness of congregations is to reflect on what principles are and what to stand up for.

The recent appointments in the US are a form of moral aggression, which is a test of our morality and willingness to acquiesce. “Appointing some anti-vaxxer to some important health position … it’s not going to shake things up; it’s just going to kill lots of people.” The idea that somehow this is okay is a form of obeying in advance. These things are unthinkable. If we think they’re okay, then you’re going along for this ride. “You can’t really have freedom without a notion of what is good…to lead you to caring about things like grace or mercy.”

A few more words of wisdom from the Mr. Snyder’s other 19 lessons in On Tyranny:

“Defend institutions…choose an institution you care about–a court, a newspaper, a law, a labor union–and take its side” (22). “Take responsibility for the face of the world. …Notice the swastikas and the other signs of hate. Do not look away, and do not get used to them. Remove them yourself and set an example for others to do so. …The world reacts to what you do” (32).

We have to widen our in-group to include the entire world, and prevent any manipulation that could possibly convince us that some people matter less:

“What might seem like a gesture of pride can be a source of exclusion. …Be wary of paramilitaries…the use of violence in the United States is already highly privatized” (43). “Be reflective if you must be armed…evils of the past involved policemen and soldiers finding themselves, one day, doing irregular things. Be ready to say no” (47). The “Holocaust began not in the death facilities, but over shooting pits in eastern Europe…regular policemen murdered more Jews than the [death squads]” (49).

“Some killed from murderous convictions. But many others who killed were just afraid to stand out. …Without the conformists, the great atrocities would have been impossible” (50). “Stand out. …It is those who were considered exceptional, eccentric, or even insane in their own time–those who did not change when the world around them did–whom we remember and admire today” (52). “Believe in truth. …If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights” (65). “Practice corporeal politics. Power wants your body softening in your chair and your emotions dissipating on the screen. Get outside. …Make new friends and march with them” (83). “For resistance to succeed…ideas about change must engage people of various backgrounds. …Protest can be organized through social media, but nothing is real that does not end on the streets” (84).

“Contribute to good causes. Be active in organizations, political or not, that express your own view of life. …Sharing in an undertaking teaches us that we can trust people beyond a narrow circle of friends” (92). “Listen for dangerous words. …Be angry about the treacherous use of patriotic vocabulary” (99).

“Be calm when the unthinkable arrives. …When the terrorist attack comes, remember that authoritarians exploit such events in order to consolidate power…the suspension of freedom of expression, the right to a fair trial. …Do not fall for it” (103). “Courage does not mean not fearing, or not grieving. It does mean recognizing and resisting terror management right away, from the moment of the attack, precisely when it seems most difficult to do” (110). “History allows us to see patterns and make judgments. …It must be hoped that [we can] become a historical generation, rejecting the traps of inevitability and eternity” (126).

This might feel like a very new struggle for many of us, but it’s been done before, and we can look back for the tools that helped us previously: