by Eric Feigenbaum

My great-grandparents were among the 12 million immigrants who passed through Ellis Island and equally a part of the wave of 20 million immigrants who entered the United States between 1880 and 1920. America’s fast-growing economy needed more manpower than its existing population had available, and the poorer classes of Europe were the beneficiaries including four million Italians (largely southern) and two million Jews.

My great-grandparents were among the 12 million immigrants who passed through Ellis Island and equally a part of the wave of 20 million immigrants who entered the United States between 1880 and 1920. America’s fast-growing economy needed more manpower than its existing population had available, and the poorer classes of Europe were the beneficiaries including four million Italians (largely southern) and two million Jews.

In many ways America was a pioneer in pioneering. In the 19th Century the United States ambitious sought to expand across a continent while developing a robust industrial economy. As the country entered the Industrial Age, it’s 1870 population of roughly 40 million just wouldn’t suffice. Therefore, America became the first Western country to undertake not just a loose immigration policy, but one at large scale – with the sheer audacity to believe it would grow its economy at unprecedented rates.

Not only did the gamble work for America, but it fundamentally changed American culture. Sure, by nature of being colonized and then in many parts staffed with abducted Africans forced into slavery, the United States began as a land of immigrants. But the 1880-1920 wave pushed the country into the Melting Pot we know today. Somehow, America decided anyone could become American if they were willing to assimilate and in turn, the country’s culture became deft at integrating arrivals.

This was not lost on the founders of Singapore. In 1921, a Republican Congress and President slammed the doors on forty years of open immigration. More than sixty years later, on the other side of the world, the government of a new, small post-colonial country grappled with how to power their economy as they moved from third world to first.

Lee Kuan Yew, the founding and longtime Prime Minister of Singapore described America as “a society that attracts talent from around the world and assimilates them comfortably as Americans.”

Only when Singapore began identifying its need for labor in the 1980s, it was already pushing through its industrial phase toward a post-industrial economy. It didn’t need unskilled labor to build railroads and work in factories and farms. The Singaporean economy was growing into sectors like finance, biotech and software.

By 1997, Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong presented a comprehensive Foreign Talent Policy based on the country’s needs and objectives. It involved three types of foreign talent:

- At The Top: CEOs, scientists, academics and artists

- Professionals such as engineers, accountants, IT professionals, teachers and administrators

- Skilled Workers such as bus drivers, technicians etc

Naturally, telling the citizens of a country which only 30 years prior had been in political and economic crisis that their government planned to bring in high-level foreign talent created concern, for which the government was prepared.

In 1989, Lee Kuan Yew assured Singaporeans the practice of immigrating foreign talent was, “for the sake of Singapore’s economy, society and politics, and would not disadvantage any Singaporean climbing the social ladder.”

A big statement.

Today, most large corporations have Talent Acquisition departments that understand a strong hire isn’t just about skills and experience, but also “fit”. Singapore took precisely the same attitude in its immigration policies – focusing on not just skilled people, but those who have greater odds of cultural assimilation. That’s why Singapore draws talent from China and India more than any other two countries, also favoring applicants from Hong Kong and Taiwan. In fact, today a little more than 500,000 Chinese nationals and 650,000 Indian nationals reside in Singapore making up 8.3 and 10.8 percent of the total population respectively.

Over time, Singapore experienced what all developed countries have – falling birth rates. Only Singapore made an unfortunate miscalculation. When it gained independence in 1965, the birth rate was 4.93 children per woman. In a struggling country, this was seen as problematic and over the next two decades, Singapore encouraged families to have no more than two children. By 1995 the Singaporean birth rate dropped dramatically to 1.57 children per woman – well below the 2.1 rate needed for Singaporeans to simply replace themselves.

While Singapore has since incentivized families to have a third child, the trend has continued reaching 1.04 births per woman in 2022. This has put more pressure on the government to carefully expand its immigration policies.

Unsurprisingly, in an upwardly mobile country with a higher per capita GDP than the United States, Singaporeans have become notably less interested in manual labor jobs. Therefore, Singapore has also had to recruit a blue-collar workforce. In some ways this took more thought to construct. While plenty of neighboring countries have no shortage of people happy to go to Singapore for blue collar jobs, Singapore is decidedly against having most of those people remain long-term and integrate with their population.

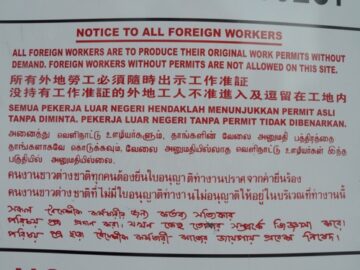

That’s why Thai, Bangladeshi and Burmese construction workers with limited visas and restricted work permits and are required to sleep in dormitories provided by the building firms for which they work. Despite however many years a Filipino, Indonesian or Sri Lankan housemaid or nanny might work for a family, they are rarely, if ever eligible for residency outside their domestic employment.

Unlike Turn-of-the-Twentieth-Century America, Singapore is clear it does not want anyone’s tired, poor, huddled masses yearning to breathe free. Only skilled labor can immigrate and even then, they have a better chance if they can smoothly assimilate.

Westerners – particularly Americans – may take issue with Singapore’s restrictive, ethnically biased and classist approach to immigration. It doesn’t give a hard-working Ghanaian or Syrian refugee opportunity to start a new life in an economically successful and stable country. Singapore embraces multiculturalism only within the box of its Chinese, Malay and Indian populace.

At the same time, Singapore’s approach to immigration is focused, transparent and clearly in the public interest. Unlike their North Americana and European friends, Singaporeans generally don’t complain about immigration at all and if they do, they’re at least clear on the cohesive strategy around it. Everyone understands the scope, purpose and methodology.

Most importantly, Singaporeans’ most common immigration anxiety tends to be about the public safety impact of having a restricted blue-collar underclass rather than whether immigration threatens citizens’ financial well-being.

For the most part, critical Westerners tend to have the hardest time with how unapologetic Singapore is for its immigration policy. But that seems to be the very point. Rather than dress up their policy with higher ideals, Singaporean leaders and citizens are clear-eyed about their choice – a sort of immigration Realpolitik.

In a time when both Americans and many of their European friends are in heated debates and domestic turmoil over immigration, the honesty and clarity Singapore brings to immigration may be something to examine. While Westerners may not necessarily find the level of consensus as Singaporeans, a coherent conversation that includes clear goals and facts would at least improve the debate and potential outcomes.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.