by Brooks Riley

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Malcolm Murray

Enrico Fermi famously asked – allegedly out loud over lunch in the cafeteria – “Where is everybody?”, as he realized the disconnect between the large number of habitable planets in the universe and the number of alien civilizations we actually had observed.

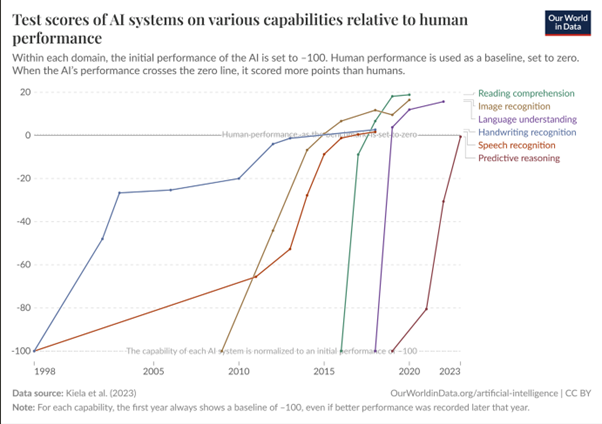

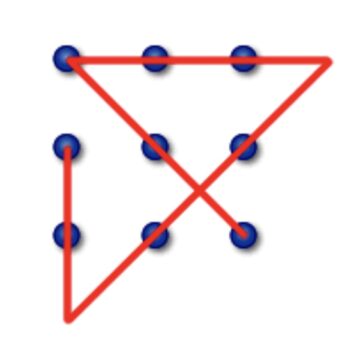

Today, we could in a similar vein ask ourselves, “Where is all the AI-enabled cybercrime?” We have now had three years of AI models scoring better than the average humans on coding tasks, and four years of AI models that can draft more convincing emails than humans. We have had years of “number go up”-style charts, like figure 1 below, that show an incessant growth in AI capabilities that would seem relevant to cybercriminals. Last year, I ran a Delphi study with cyber experts in which they forecast large increases in cybercrime by now. So we could have expected to be seeing cybercrime run rampage by now, meaningfully damaging the economy and societal structures. Everybody should already be needing to use three-factor authentication.

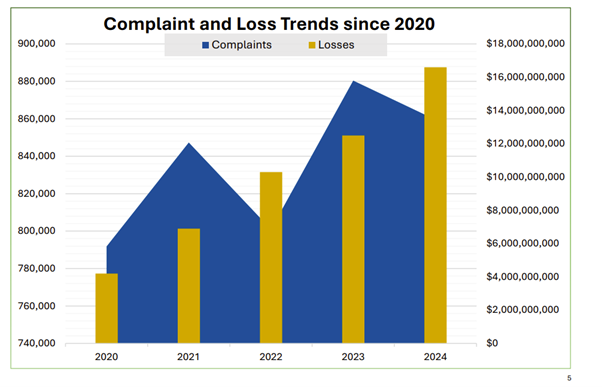

But we are not. The average password is still 123456. The reality looks more like figure 2. Cyberattacks and losses are increasing, but there is no AI-enabled exponential hump.

So we should ask ourselves why this is. This is both interesting in its own right, as cyberattacks hold the potential of crippling our digital society, as well as for a source of clues to how advanced AI will impact the economy and society. The latter seems much needed at the moment, as there is significant fumbling in the dark. Just in the past month, two subsequent Dwarkesh podcasts featured two quite different future predictions. First, Daniel Kokotajlo and Scott Alexander outlined in AI 2027 a scenario in which AGI arrives in 2027 with accompanying robot factories and world takeover. Then, we had Ege Erdil and Tamay Besiroglu describing their vision, in which we will not have AGI for another 30 years at least. It is striking how, while using the same components and factors determining AI progress, just by putting different amounts of weight on different factors, different forecasters can reach very different conclusions. It is like as if two chefs making pesto, both with basil, olive oil, garlic, pine nuts, cheese, but varying the weighting of different ingredients, both end up with “pesto,” but one of them is a thick herb paste and the other a puddle of green oil.

Below, I examine the potential explanations one by one and how plausible it is that they hold some explanatory power. Finally, I will turn to if these explanations could also be relevant to the impact of advanced AI as a whole. Read more »

by Barry Goldman

When I get up in the morning I drink a pot of coffee and read the paper. The coffee makes me irritable. The paper makes me furious and miserable. That sets the tone for the rest of the day.

I agree with Ezra Klein that the constitutional crisis is not coming, it is here. When the Trump administration can ignore a unanimous ruling of the Supreme Court, the breakdown of the rule of law is not threatening, it has arrived.

I am a lawyer. I speak the language. I faithfully listen to Talking Feds and Strict Scrutiny, and I read the relevant Substacks. But I’m afraid all the smart lawyers in all those places are making the same mistake. The Trump people don’t give a damn about the definition of “invasion” or “predatory incursion” under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. And they don’t give a damn about the difference between “facilitate” and “effectuate” in the Supreme Court’s order in the Abrego Garcia case. Arguing about legal definitions with Trumpers is playing chess with a pigeon. The pigeon knocks over the pieces, shits on the board, and struts around like he won. Pigeon chess has nothing to do with chess, and Trump administration litigation has nothing to do with law. This realization accounts for what I have taken to calling my macrodepression.

When I’m done with the paper and my daily dose of legal commentary, I sit down at my desk and toggle to microdepression. I look at my email. Inevitably, the people I’m looking forward to hearing from have not written. The people who have written are either cancelling something it took weeks to schedule, trying to sell me something I don’t want, or writing to tell me another one of my friends is sick or dead.

Then the phone starts ringing. Read more »

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025.

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Martin Butler

In the 1980s being non-judgmental was very much in vogue. The idea was that you should withhold from morally judging other people and their actions, at least in a significant number of cases. It was an imperative that I came across in all sorts of contexts. I, however, thought it very misguided. Why should we be non-judgemental? It seemed like an abdication of our moral commitments, a kind of moral cowardice. And in any case, I thought it almost impossible not to judge other people and their actions. Of course we might choose not to voice those judgements, and perhaps this is what those promoting the non-judgmental attitude really meant. At the time I thought non-judgmentalism resulted from a half-baked moral subjectivism, the idea that there is no objective right or wrong and so I shouldn’t expect the actions of others to meet my own subjective moral standards – to do so would be an illegitimate imposition of my morality onto others.

Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

A moral theory that at least appears to justify a limited form of non-judgmentalism is the moral philosophy of liberalism as presented by John Stuart Mill. This is encapsulated in the harm principle: we should be allowed to act as we want provided we don’t harm others. But of course this doesn’t stop us judging the actions of others, it merely requires that we don’t interfere or attempt to curb those actions simply because we disapprove of them, with the proviso that others are not harmed. Although it is notoriously difficult to establish a clear definition of ‘harm’, the virtue of this approach is that it allows for a distinction between what we might regard as morally wrong and what the state should outlaw. Judging something offensive, for example, cannot be regarded as sufficient grounds for it to be outlawed. It does not however get to the nub of what non-judgmentalism is about. Read more »

by Eric Schenck

There are two types of readers: People that can read just about anywhere, and those that prefer a specific location to do it. I’m the second one. To describe where I’ve done most of my reading, I use the phrase “reading place.”

“Reading spot” sounds too specific. “Reading nook” also isn’t quite accurate.

I’ve had a number of reading places throughout the years, and they’ve all given me something different. Here are just a few of them…

It starts in my parent’s backyard. My first reading place is a deck. It’s big and brown and you get slivers if you’re not careful. Some of my first memories are on this deck, and some of my very first books are read here.

I have a variety of reading places as I get older. One of my favorites is my car. It’s named Marvin, and it’s a 1995 Mercury Grand Marquis. Along with baseballs and fast food wrappers, I also store books. Some of them are from my high school classes. Others are stolen from my sister. I lean back in the front seat, after school ends and before baseball practice starts, and knock out a few pages.

By the time I make it to college, my reading place loses a bit of it’s character. Gone is a place specific to me, and in comes one that is applicable to just about everybody: the school library.

It’s still wonderful, though. I’m surrounded by fellow readers that love learning for the sake of it and aren’t afraid to get into nerdy conversations. It makes me feel like I’ve found my people. I like to look at books I’ll never read and imagine I will. It’s my first struggle with tsundoku (getting more books than you can actually read).

My first two years at college, this is where most of my reading happens. There’s no place in particular – usually whatever study room I can find that’s still empty.

The last two years is where I find my place. Read more »

“Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,”

a poet said imagining friendly neighbors

working their way along that which stood between

resetting fallen gneiss and granite loaves and balls

fallen to each to keep their wall intact

while one questioned the irony of friendly walls

and the other made a prima facie case

for an inherent friendliness

in their practicality

so, we’ve had walls and walls remain,

not of stone but of blood and bone,

walls built of double helixes

spiraling through time,

hydrogen-mortared pairs of

adenine guanine cytosine thymine,

walls smaller than any past poet’s wall-builder

might imagine, but centuries stronger

than Hadrian’s real or Alexander’s

mythic wall which locked the Gogs

and Magogs of alien tribes

behind stone or iron blocks

to keep the builders safe from

differences that barely exist

in the protein hieroglyphics

of nature-made chemical bonds

of a double helix making us Gogs

and Magogs of each other

as we spiral through worlds

hurting and killing to uphold

our imagination’s chronic

belief in quixotic walls

and spurious distinctions

which heap between us

grudges and grief

Jim Culleny

12/13/16

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Angela Starita

Driving through Journal Square in Jersey City with a friend, we’re both amazed by the construction that has happened there in the last two years. In this case, amazement is a form of horror: the new buildings, an array of towers, are grotesquely out of scale with the rest of the city. The worst offender is a blue-glass behemoth calling itself The Journal, the name serving as the only reference to its setting in Journal Square. As you head north, Kennedy Boulevard, the city’s main thoroughfare, veers to the left and heads up to Union City, West New York, and North Bergen. Until a few years ago, that curve underscored the Boulevard’s role as a connector, a common thread and organizing principle of those Hudson County towns, starting to the south in Bayonne. Now the approach to the Square is dwarfed by the new building, one of dozens that have gone up in a 10-block radius in fewer than 5 years. The road itself goes unimpeded, but visually the building creates a massive visual wall, intimidating, arrogant, an absolute full stop.

My friend says what he dislikes most about so much new construction is its uniformity, so unrelated to the specifics of a place. I do a bad job trying to explain the roots of un-placeness in Modernist architecture: how after the bloodshed of World War I, European architects thought they had a duty to create work that could be, as they saw it, universal. I talk about Le Corbusier’s design of the Villa Savoye as its own system, regardless of landscape, that could be plugged into almost any setting. It was like making an Esperanto for space, I say; the idea was to supersede national styles and create buildings that met people’s needs without recourse to ornament or any device that covered structural “truth.” To these architects, if our organization of space could literally foster communication, maybe prevent even war. I want my friend to see that whatever the motivations of developers, the history of architecture as disconnected object has at least some noble roots. Well, he said, I still don’t like that it has nothing to do with where it’s being built.

Solutions to the problem at the heart of our exchange—how to shape, update, and expand a physical environment with integrity—have been varied and frequently polemical: the tabula rasa approach of Le Corbusier, in some ways epitomized by Brasilia, is a frequent if misunderstood whipping boy of both urbanists and the public. And while there’s a complex and sometimes poignant story behind those plans, I can’t disagree that the results of such ready-made towns—those designed by famous architects as much as the off-the-shelf developments across the country—are alienating. And of course, the blank-slate philosophy is appealing in a country where economic health is measured in housing starts. In Florida, my father’s town bought his tiny neighborhood, mostly woods, via eminent domain. Their nominal object was to create a more walkable environment by tearing down the existing houses and building new houses along with a nearby shopping street. When I asked a town manager, why not just incorporate the existing dozen or so houses into the plan, he claimed that developers only want a blank slate. Who knows if this was accurate or not, but he certainly told the truth when I asked why do this at all? “That area doesn’t generate enough income.” Read more »

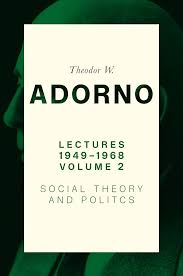

by Eric J. Weiner

Many people familiar with Theodor Adorno and his work in sociology, philosophy, psychology, and cultural studies might not know about his work as a public intellectual in postwar Germany. For those readers who are not familiar with his legacy, this book is a perfect introduction to some of his most important ideas concerning free will, self-determination, and the persistence and influence of authoritarian structures in democratic and capitalistic systems. As a public intellectual, Adorno steps out of the shadow of academia and the Institute for Social Research. The lectures in this book, all delivered between 1949-1963, are not only accessible to lay readers but remain relevant to our world today. The insights he offers in reference to postwar German society are remarkably still applicable to 21st century neoliberal democratic societies. However different the 21st century is to the 20th, especially regarding technology and globalization, his analyses remain relevant to our current times. In some instances, they are even more relevant today than when he first delivered them.

In 2025, as authoritarian discourses arise like ghosts from what might appear to be the cold ashes of 20th century fascism, Adorno’s work suggests that maybe they never really disappeared in the first place. From his perspective, what we are seeing in the United States and across the globe is a continuation of a hegemonic system of thought and behavior–and the consciousness that it engenders–that was never fully eradicated. Just as the “end of history” thesis was premature in announcing the triumph of western capitalism and democracy in the 1980s over communism, announcing victory over the ideology of authoritarianism and fascism in the west at the end of World War II is also beginning to look politically naïve and willfully ignorant.

Defeating Hitler’s Third Reich militarily was not the same thing as extinguishing the ideas that fueled its popularity and fed its imperialistic and murderous imagination. Indeed, as the work of the Institute for Social Research consistently revealed, the proverbial rock from under which Hitler and Nazism crawled was made from a familiar and seemingly innocuous amalgam of science, philosophy, education, nationalism, and culture none of which, together or separately, gave away the unforeseen terror that was hiding in plain sight. From the time of Adorno’s public lectures to our current time, the task during these transitional periods of history is not to predict, like astrologists mapping the stars for clues about what the future holds. In these times, speculative social science, for Adorno, is no better than a crystal ball. Trying to guess at what will be at the expense of understanding and changing what is, is a fool’s goal. For Adorno, resistance to the rise of neo-fascist discourses in the postwar era is first and foremost to ask, “How these things will continue, and [taking] responsibility for how they will continue” (186). This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t have a social imagination. But this is decidedly different than believing that we can actually know what the future holds. We should imagine what could be, as any tangible notion of educated hope depends on a vibrant social imagination, but we first must change, according to Adorno, our relationship to what is.

In what follows, I will discuss several points of entry from Adorno’s lectures into how and why right-wing extremism continues to thrive in the 21st century and the central role of education and culture in combatting or perpetuating these extremist ideologies. Read more »

by Mark R. DeLong

Roger Ebert labeled it the one movie “entirely devoid of clichés.” “It should be unwatchable,” he said, “and yet those who love it return time and again, enchanted.” It was My Dinner with André, which I watched with my wife and a couple of friends at the Carolina Theatre in Durham, North Carolina, back in 1981 when the movie was released. Years later, I picked up a used VHS of the film and baffled my children with it.

One scene struck me from the first viewing, and my memory has returned to it especially in recent months. Toward the end of their dinner, Wally (Wallace Shawn) and André (André Gregory) discuss matters of preserving culture—or perhaps, more accurately, André steers the conversation through his wild and impossible adventures in new age-y communities, recounting events that would defy the laws of physics or at least stretch our imaginations.1For instance, a community, “Findhorn,” that built “a hall of meditation” seating hundreds of people with a “roof that would stay on the building and yet at the same time be able to fly up at night to meet the flying saucers.” Findhorn actually exists, though the architecture that André describes was fanciful, to say the least. The fascination with flying saucers was real, though, in the 1960s, when a leader of the Findhorn community felt that extraterrestrials could be contacted via telepathy and the community built a landing strip for the saucers.

One of the leaders of such a group, André says, was “Gustav Björnstrand”—a fictional character, not a real “Swedish physicist” as André claims—who is trying to create

a new kind of school or a new kind of monastery … islands of safety where history can be remembered and the human being can continue to function, in order to maintain the species through a Dark Age. In other words, we’re talking about an underground, which did exist during the Dark Ages in a different way, among the mystical orders of the church. And the purpose of this underground is to find out how to preserve the light, life, the culture. How to keep things living.

Wally listens, entranced but not convinced that André’s unhinged stories make sense. He’s “just trying to survive,” he says, and takes pleasure in small comforts: dinner with his girlfriend, reading Charlton Heston’s autobiography, sleeping under a warm electric blanket on cold New York nights. “Even if I did feel the way you do—you know, that there’s no possibility for happiness now,” an exasperated Wally replies to André, “then, frankly, I still couldn’t accept the idea that the way to make life wonderful would be to totally reject Western civilization and to fall back to a kind of belief in some kind of weird something.” Read more »

by Charles Siegel

“The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers” is one of Shakespeare’s most famous lines. It lives on, four centuries after it was written, on countless t-shirts and coffee mugs. People who have never read another word of Shakespeare know the line well, and think that Shakespeare hated lawyers and that his audiences hated them too. That facile reading, however, is wrong.

Shakespeare used lawyers frequently, as both a plaintiff and defendant, and moved freely in legal circles. His first residence in London was near the Inns of Court, where affluent students lived and studied law, and he had friends and relatives in the Inns. It thus seems unlikely that Shakespeare hated lawyers or held them in contempt. But it is the context in which “let’s kill all the lawyers” appears that most tells us what it really means.

The line is spoken by Dick the Butcher, the henchman of Jack Cade. In Henry VI, Part 2, the boy king has returned from France, and rival factions from the Houses of York and Lancaster are struggling for power. The Duke of York hires Cade, a commoner, to foment rebellion. Cade tries to rouse a crowd of people, and Dick chimes in:

JACK CADE: Be brave, then; for your captain is brave, and vows reformation. There shall be in England seven half-penny loaves sold for a penny: the three-hoop’d pot shall have ten hoops; and I will make it felony to drink small beer: all the realm shall be in common; and in Cheapside shall my palfrey go to grass: and when I am king,– as king I will be,–

ALL. God save your majesty!

JACK CADE: I thank you, good people:– there shall be no money; all shall eat and drink on my score; and I will apparel them all in one livery, that they may agree like brothers, and worship me their lord.

DICK: The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.

Shakespeare is saying that lawyers are what stand between order and chaos, between respect for individual rights and mob rule. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens agreed, writing in a 1985 opinion that “a careful reading” of the scene that shows that “Shakespeare insightfully realized that disposing of lawyers is a step in the direction of a totalitarian form of government.”

Today Donald Trump and his minions aren’t trying to kill lawyers. But he does seek totalitarian government, and he certainly wishes to dispose of lawyers, and the rules and norms, the rights and processes, that they guard. Read more »

by Jerry Cayford

I listened some weeks ago to a terrific discussion between Ezra Klein and Fareed Zakaria. And it really was terrific. They were both at the top of their game, doing a certain thing at a very high level. Still, I have a slight bias against both these guys, and complicated feelings about what they do so well. My pleasure in their intelligence was tinged with frustration that they aren’t better, and with a slight melancholy about the path not taken. Critique mixed with autobiography. I was supposed to be them.

I knew early on that my father did not aspire for me to be president, like other boys’ fathers did, but rather to be the president’s closest adviser. I was supposed to grow up to be McGeorge Bundy—to pick a name from when I was first imbibing this career plan—I was supposed to become Jake Sullivan, to pick someone recent. And if I did not make it quite that close to the seat of power, well, I was still supposed to be Ezra Klein or Fareed Zakaria or some other talented policy analyst, saving the world through the practice of intellectual excellence.

What Klein and Zakaria practice are “the critical and analytical skills so prized in America’s professional class,” to use a phrase from an article of a couple decades ago unearthed by Heather Cox Richardson—another excellent practitioner—about the Bush administration’s replacement of critical and analytical skills with faith and gut instinct. Richardson recalls a passage from that article strikingly suggestive of Donald Trump’s current administration:

These days, I keep coming back to the quotation recorded by journalist Ron Suskind in a New York Times Magazine article in 2004. A senior advisor to President George W. Bush told Suskind that people like Suskind lived in “the reality-based community”: they believed people could find solutions based on their observations and careful study of discernible reality. But, the aide continued, such a worldview was obsolete. “That’s not the way the world really works anymore…. We are an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors…and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

In our era of conspiracy theories, fake news, and relentless lies, this rejection of the “reality-based community” sounds like a conservative confession of contempt for truth. It is easy to mock, and both Suskind and Richardson don’t hold back.

And yet, beneath the Bush official’s unfortunate phrasing is a point that is basically right. Read more »

A stained-glass window in a wall on the other side of this chapel in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, seen through a stained-glass window on this side.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Akim Reinhardt

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

They faced a very mild incline and moved slowly as they talked and laughed with each other. To me, it seemed almost idyllic, a visage from a different era. Then my friend said, “I feel sorry for those kids. It’s like their parents aren’t paying attention to them.”

When I was a child playing with my friends, I think the very last thing I wanted was my parents paying attention to me.

My friend is a Baby Boomer, and like me, has no children. He and I grew up in eras when children did exactly what these two were doing: play outside without adult supervision after school, on weekends, and during the summer. It was so common and normal during our childhoods that absolutely no one questioned it. And didn’t he, like I, have fond memories of that? Of course he did, he admitted. So why, I asked, was he pitying these kids for doing the same thing?

“Wellll,” he thought aloud, searching for an explanation, “things are different now.”

They certainly are. For starters, childhood has never been safer. Bike helmets and playgrounds atop soft padding instead of blacktop are just two small examples.

But the elimination of many dangers is not the only thing different today. Parents are also different. Or at least the middle class ones are. For let’s not fall into the trap of having the middle class stand-in for a nation at large, even if politicians and the press constantly promote this misrepresentation, which erases tens of millions of Americans who are poor, work and commute excessively, and don’t have the wherewithal to over-parent their children. Whereas middle class parents can find a combination of time and resources to ensure their children are chaperoned and overseen pretty much 24 hours a day. Read more »

by Eric Feigenbaum

The smell of Thai Boat Noodles always reaches to the parking lot. As you walk further into the Weekend Food Market at the Wat Thai of Los Angeles, whiffs of fish sauce, shrimp paste, garlic, frying rice noodles and more start to chime in. But always the Boat Noodles.

“This smells like Thailand!” my eleven-year-old son said the first time I took him last year.

Of any country I’ve ever visited, Thailand by far has the best developed and varied street food scene. Like my son said, the smells are both strong and recognizable. In Bangkok there are streets, back alleys, parks, bus stations and train depots that could vie for best “restaurant” in the world if they were somehow formally organized. During the time I lived in Thailand, I used to consider the Southern Bus Terminal my favorite buffet because of the combination of food carts and vendors.

In Thailand, delicious food is cheap and ubiquitous. It also makes for messy streets and back alleys – which are the heart of Bangkok neighborhoods. Sidewalks can be overtaken by food sellers with their makeshift tables and stools. Food vendors often occupy narrow lanes in alleys and interfere with the flow of traffic even on main roads. Thai culture has a high tolerance for disorganization many Americans might consider near-chaos.

Every Southeast Asian country has street food and the disorganization it brings to streets and sidewalks. The food is a treasured part of their cultures and also a major convenience. Good, healthy, tasty food at a reasonable price can be steps from your home or business.

In 1965 when Singapore achieved independence, it was no different from its neighbors. In fact, it may have rivaled Thailand for an incredible and chaotic street food scene. Singaporean street food not only features the many specialties of its major constituent cultures – Chinese of numerous regions, Malay and Tamil Indian – but as one might expect of a multi-cultural island, people began experimenting with fusion. A little Malay spice in a traditionally bland Chinese noodle dish…. An Indian-inspired curry sauce to accompany a Malay staple…. Fish head curry becoming a national dish. Same with pepper crab and laksa.

Singaporeans loved their street food. Only their government hated that it was on the street. Read more »

by Rafaël Newman

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics.

If I were asked to name the creed in which I was raised, the ideology that presented itself to me in the garb of nature, I would proceed by elimination. It wasn’t Judaism, although my father’s parents were orthodox Jewish immigrants from the Czarist Pale, and we celebrated Passover with them as long as we lived in Montreal. It certainly wasn’t Christianity, despite my maternal grandparents’ birth in protestant regions of the German-speaking world; and it wasn’t the Communism Franz and Eva initially espoused in their new Canadian home, until the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact put an end to their fellow traveling in 1939. Nor can I claim our tribal allegiance to have been to psychoanalysis, my mother’s professional and personal access to secular Jewish culture, although most of my relatives have had some contact, whether fleeting or intensive, paid or paying, with psychotherapy—since the legitimate objections raised by many of them to the limits of classical Freudian theory prevent it from serving wholesale as our ancestral faith, no matter the extent to which a belief in depth psychology and the foundational importance of psychosexual development informs our discussions of family dynamics.

No, our house religion was social democracy.

Our family commitment to sexual and racial equality, socialized medicine, decolonization, and government regulation of the market was manifest, of course, in a geographically and historically conditioned form: in electoral loyalty to the NDP, Canada’s mainstream progressive party, founded in 1932 as the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and renamed the New Democratic Party in 1961. Our family credo held that the Liberal Party of Canada, known as the Grits, might look progressive enough, but their instincts would always be pro-business; any socially progressive policies they may have championed had been forced on them by their marriages of parliamentary convenience with the New Democrats. As for the Tories, Canada’s Conservatives, they were simply out of the question for progressives: it’s in the name. My choice of the NDP in the ballot box, when I came of voting age, was thus at once more, and less, than a deliberate commitment: it was a reflex, almost an instinct. It was second nature.

My first proper induction into retail politics was at the age of 14, several years before I was eligible to vote; and it involved working on a by-election campaign for the local NDP candidate in our Ontario riding of Broadview. Before we moved east to Toronto, from the Vancouver suburbs where we spent the mid-1970s, I had already twice ventured into political activism: once visiting a meeting of the local Trotskyist cell, where I was amazed to encounter my high school French teacher; and once at a rally for divestment by Canadian banks in then-apartheid South Africa. (This is not counting my fabled instrumentalization as an infant, when my mother protested the sale of Californian grapes at our local Steinberg’s grocery store in 1960s Montreal, holding me aloft, like Andromache for extra pathos, as she cited Cesar Chavez and the NFWA.)

Now, in 1978, freshly arrived in our new home in east-central Toronto, I was encouraged by my parents to volunteer in support of Bob Rae, who would go on, at 30, to win his first federal seat for the NDP that October and would remain a member of parliament for over two decades. Read more »

by Marie Snyder

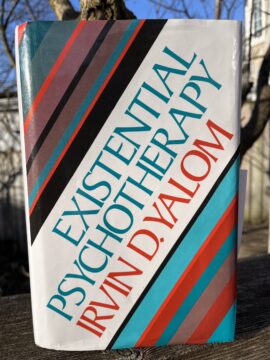

About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an existential sickness, and these cases require a different method of treatment. We experience this lack of purpose as boredom, apathy, or emptiness. We are “not told by instinct what one must do, or any longer by tradition what one should do. Nor does one know what one wants to do,” so we feel lost and directionless. Instead of addressing meaninglessness as the problem, though, we’ve been merely addressing the symptoms of it: addictions, compulsions, obsessions, malaise. In today’s context, it might suggest that even social media issues could be problems with a lack of meaning.

About 45 years ago, psychiatrist Irvin Yalom estimated that a good 30-50% of all cases of depression might actually be a crisis of meaninglessness, an existential sickness, and these cases require a different method of treatment. We experience this lack of purpose as boredom, apathy, or emptiness. We are “not told by instinct what one must do, or any longer by tradition what one should do. Nor does one know what one wants to do,” so we feel lost and directionless. Instead of addressing meaninglessness as the problem, though, we’ve been merely addressing the symptoms of it: addictions, compulsions, obsessions, malaise. In today’s context, it might suggest that even social media issues could be problems with a lack of meaning.

The last sentences of his lengthy tome, Existential Psychotherapy, sum up his solution: “The question of meaning in life is, as the Buddha taught, not edifying. One must immerse oneself in the river of life and let the question drift away.” How he lands here is an intriguing path through a slew of philosophers and psychiatrists. Even without symptoms of a problem, attention to meaning is necessary as it gives birth to values, which become principles to live by as we place behaviours into our own hierarchy of acceptability.

“One creates oneself by a series of ongoing decisions. But one cannot make each and every decision de novo throughout one’s life; certain superordinate decisions must be made that provide an organizing principle for subsequent decisions.”

Yalom doesn’t suggest coming up with a list of values that can become meaningful to us, but that we immerse ourselves in life to become more aware of which values we already have. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Aerial composition, March, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Aerial composition, March, 2025.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Michael Liss

April 1, 1865. For the South, the end is nearing. It was already obvious on March 4, when Abraham Lincoln delivered his magnificent Second Inaugural Address. Four weeks later, it is more obvious. For all the bravery of the Confederacy’s men and all the talent of its military leadership, its resources are almost gone. A great test, possibly a decisive one, awaits it at the Battle of Five Forks, Virginia. For more than nine months, Union and Confederate forces have been punching and counterpunching around the besieged town of Petersburg. The stalemate has cost more than 70,000 casualties, expended stupendous amounts of arms and supplies, and caused great civilian suffering, but, to Grant’s endless frustration, success has eluded his grasp. This time would be different. At Five Forks, one of Grant’s most able generals, Philip Sheridan, defeats a portion of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under General George Pickett. The price, for an army with nothing more to give, is nearly fatal—1,000 casualties, 4,000 captured or surrendered, and, even more crucially, the loss of access to the South Side Railroad, a major transit point for men and material.

April 2, 1865. The strategic cost of Five Forks is driven home. Robert E. Lee abandons both Petersburg and Richmond. Jefferson Davis and his government flee, burning what documents and supplies as they can. Lee moves his army West toward North Carolina, hoping to escape Grant and join up with Confederate forces under General Joseph Johnston. The loss of Richmond is much more than symbolic—it had also been a critical manufacturing hub, and it contained one of the South’s largest hospitals—but Lee realized Richmond was a necessity that had become a luxury. To stave off a larger defeat, he had to save his army. The last hope for the Confederacy depended on it. If Lee and his men could stay in the field, move rapidly, inflict damage, prolong the conflict, then they still had a chance. Lee thought it possible, but he was running out of everything—clothes, food, ammunition, and even men. It wasn’t just casualties that caused his army to shrink. Estimates are that at least 100 Confederate soldiers a day were simply deserting, driven by fear, hunger, and plaintive words from home.

April 3, 1865. Richmond and Petersburg fall, as United States troops occupy both. A day later, the fantastical happens. Lincoln, accompanied by son Tad and the most appallingly small security contingent, visit Richmond. The risk is stupendous—the city is burning, the harbor is filled with torpedoes, and potential assailants lurk literally anywhere. But the scene is incredible. It’s Jubilee for the slaves, some of whom fall to their feet when they recognize the tall man in the top hat. Now freed men, they gather, march, shout, and sing hymns. To tremendous cheers, Lincoln walks to the “Confederate White House,” climbs the stairs, and plunks himself down in a comfortable chair in what had been Jefferson Davis’s study. Read more »