by Ashutosh Jogalekar

John von Neumann emigrated from Hungary in 1933 and settled in Princeton, NJ. During World War 2, he contributed a key idea to the design of the plutonium bomb at Los Alamos. After the war he became a highly sought-after government consultant and did important work kickstarting the United States’s ICBM program. He was known for his raucous parties and love of children’s toys.

Enrico Fermi emigrated from Italy in 1938 and settled first in New York and then in Chicago, IL. At Chicago he built the world’s first nuclear reactor. He then worked at Los Alamos where there was an entire division devoted to him. After the war Fermi worked on the hydrogen bomb and trained talented students at the University of Chicago, many of whom went on to become scientific leaders. After coming to America, in order to improve his understanding of colloquial American English, he read Li’l Abner comics.

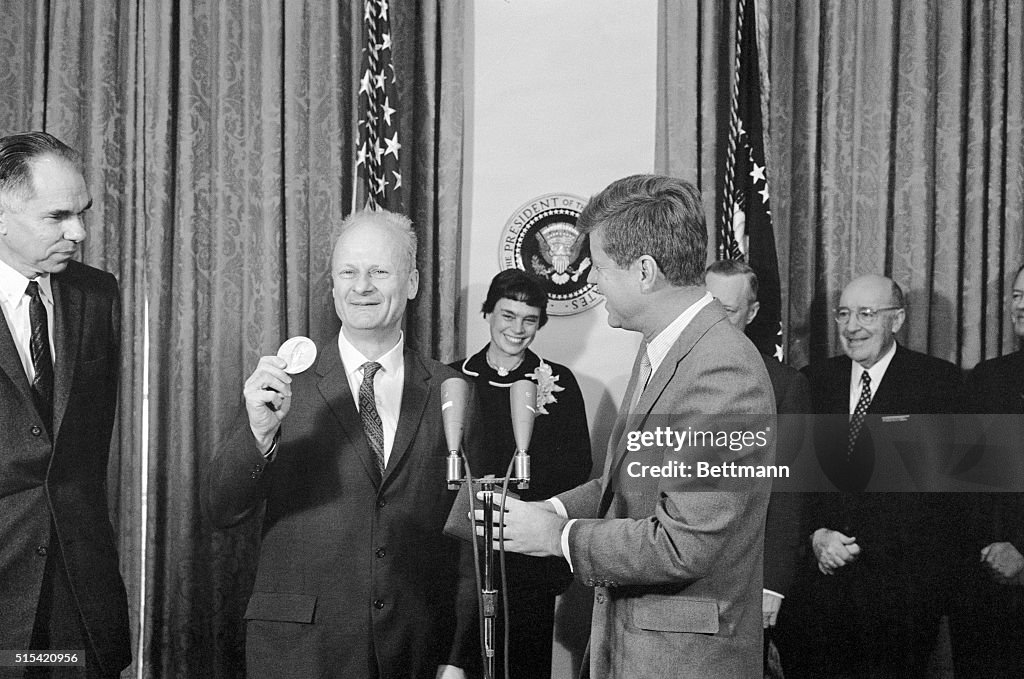

Hans Bethe emigrated from Germany in 1935 and settled in Ithaca, NY, becoming a professor at Cornell University. He worked out the series of nuclear reactions that power the sun, work for which he received the Nobel Prize in 1967. During the war Bethe was the head of the theoretical physics division of the Manhattan Project. He spent the rest of his long life working extensively on arms control, advising presidents to make the best use of the nuclear genie he and his colleagues had unleashed, and advocating peaceful uses of nuclear energy. He was known for his hearty appetite and passion for stamp collecting.

Victor Weisskopf, born in Austria, emigrated from Germany in 1937 and settled in Rochester, NY. After working on the Manhattan Project, he became a professor at MIT and the first director-general of CERN, the European particle physics laboratory that discovered many new fundamental particles including the Higgs boson. He was also active in arms control. A gentle humanist, he would entertain colleagues through his rendition of Beethoven sonatas on the piano.

Von Neumann, Fermi, Bethe and Weisskopf were all American patriots.

They had all fled fascism in Europe. They came to this country because the United States offered them their best hope for what Franklin Roosevelt had called “freedom from fear”. They all came to love this country, contributed immensely to its defense and scientific leadership and trained an entire generation of scientists that continues to preserve American excellence in research and produce a surfeit of Nobel Prizes. Apart from the vast scientific and technological resources that this country offered them, all of them greatly appreciated Americans’ lack of formality, easygoing nature, respect for individual freedom and leveling of social class. They felt entirely at home in America. In a moving letter that Bethe sent to his former advisor Arnold Sommerfeld after the war, in response to a plea from Sommerfeld to return to his native country, Bethe wrote that America was his native country, that he felt like he had been born in Germany by accident, that Sommerfeld needed to understand what he loved about America.

All four of these scientists were patriots, but they had different political bents. Von Neumann and Fermi were politically conservative and Eisenhower Republicans. Bethe and Weisskopf were politically liberal, lifelong Democrats. Their political differences made not an iota of difference to their service to this country, because they believed that patriotism and love of country should transcend political partisanship. At the same time, they always believed that America, while being a leader, should never become a bully, should always build international coalitions, and rather than leading other countries by the collar, should lead by example. While working ceaselessly for international cooperation between America and the rest of the world, these scientists never apologized for building a strong America that could respond to threats if needed. Peace, but through strength, was their mantra. The four also remained cordial colleagues and friends because they strongly believed that human relationships should not be defined by who you vote for.

Twenty years after the war ended, the work and vision led by these scientists and many others including Wernher von Braun came to fruition as America put a man on the moon. The vision had been given inspiring shape by President Kennedy in 1962 in his famous “moon speech” at Rice University. In a football stadium filled with scientists, engineers and administrators, Kennedy said, “We choose to go to the moon not because it’s easy but because it’s hard.” One important goal of the speech was to set the terms in the space race with the Soviet Union, but there is no doubt that Kennedy genuinely believed in the vision. In addition to being one of the most inspiring speeches ever given by an American president, the address was also notable for its sheer level of detail, laying out the dimensions of the rocket, the composition of its materials and the temperatures these materials would have to endure. It was a time when an American president felt comfortable eloquently piling technical fact after fact in his speech, and the audience felt comfortable listening to these facts. The address is almost an ideal mix of what makes America unique – its constant capacity to innovate and its constant capacity to dream big.

Kennedy’s vision came true in 1969 when Apollo 11 put men on the moon. Perhaps the most striking detail in that mission was the plaque the astronauts put on the Moon – “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon in 1969, A. D. We came in peace for all mankind”. Even though America had single-handedly spearheaded the moon mission, the mission did not claim American ownership. The plaque did not say “Men from America” but “Men from the planet Earth”. And it said that the astronauts had come in peace for all humanity. This was the pitch-perfect balance of technical and human accomplishment that America represented back then – meeting ungodly technical challenges, leading for all humankind with innovation and without rancor, uniting in service of a common goal and putting country over party.

Today more than ever, we need the same vision of purpose, patriotism, sacrifice and scientific excellence that animated von Neumann, Bethe, Weisskopf and Kennedy. This vision today faces challenges different from those the country faced in 1969. There is no Cold War and no Soviet Union bent on annihilating us, but there is a China which is bent on becoming a superpower, more benign but no less persistent and vastly more technologically and economically competent than the Soviet Union. Other countries are fast catching up as well. Whether it is AI or chip manufacturing, self-driving cars or genetic cures for diseases, China and other nations don’t lack for good scientists and engineers, and their stated purpose is to become the leader in these diverse fields of science and technology. While many of these inventions have originated in the United States, other countries are poised to reap their benefits. Nobody should be denied the benefits of new scientific discoveries, but in a world where every country is vying to become number one in these fields, it is paramount that the United States preserves its leadership and edge.

Unfortunately, the most significant challenge facing continued American leadership may not be technical or even economic; it is social and political. As the media never tires of pointing out, America is more politically divided than ever. Not just politicians but ordinary citizens are increasingly loathe to reach across the aisle, to find common ground between themselves and other citizens who they consider to be their steadfast opponents. We have seen a chilling effect on free speech even as opinions and disagreements are treated as acts of disloyalty to a cause or ideology and nuances or differences of degree are ignored. Perhaps the most damning symptom of the lack of American dynamism is the fatal belief floated in many corners of the political field that America’s best days are behind her and that the country can no longer live up to its founding ideals.

Because of such beliefs, patriotism has become a dirty and misleading word. At the very least, it seems to have fallen out of fashion as either pointless or dangerous. Accompanying this dismissal is a general cynicism about believing in the basic American idea of progress. Patriotism is detested on one side because that side often mistakes patriotism for nationalism and believes that being a patriot means being a white supremacist or a jingoistic warmonger or something of that ilk, a perception that some on the other side are only too happy to reaffirm through their behavior. When Donald Trump won the election in 2016, he rode on his promise to end “globalism”. His promises were founded on a dog-whistle mix of toxic nativism and xenophobia, but the reason they resonated with so many people was because these people believed that many American political leaders and citizens are privileging the world at large over America. More than two decades of rampant offshoring and outsourcing of key goods and services by both parties, developments that left entire towns’ workforces decimated and out of jobs, made it easy to shore up these beliefs and lent an unintended grain of truth to Trump’s rants.

But we must look through to the truth of patriotism through the distorted lens of nativist xenophobia on one hand and well-meaning but enervating globalism on the other. It was a truth that the emigre scientists above understood well. For this it is necessary to affirm several facts, and two in particular.

Firstly, patriotism means recognizing your country’s unique values. If you believe there is nothing unique about your country, why would you think it’s worth fighting for? The fact is that contrary to what we may have heard, the demise of American values is greatly exaggerated. The United States is still unique in its respect for individual rights, most notably through the First Amendment that guarantees freedom of religion and freedom of speech without qualification; to understand how unique, you only have to look at the transgression of free expression even in the world’s largest democracy. When such transgressions are seen in the United States, citizens act. When the distinguished Indian astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar became an American citizen in the 1950s, he said that the main reason he felt compelled to acquire citizenship was because he was very concerned by the growth of McCarthyism and therefore wanted to support Adlai Stevenson’s bid for the presidency.

The United States is still unique in having a highly distributed political system that enables the separation and sharing of power, preventing any one faction from grabbing it. It is still the world’s biggest melting pot, a swirling cauldron of creativity and struggle where people around the world make their lives and thrive. And in the list of things that many of us take for granted, America has also been very good about enforcing laws that lead to what can be called “civic commonsense”; there is a basic sense of etiquette and law and order in everyday public life, whether it pertains to obeying the rules of the road or lining up in public and private facilities, that is missing in many other countries.

On the scientific and technological front, while other countries have caught up, the United States still has the world’s best research universities and best companies, produces the best scientists and engineers and publishes the most innovative patents and papers. In internet technology, artificial intelligence, new cures for serious diseases and defense technologies, America still leads the way. Its academic and startup environments still provide the best opportunities for cutting-edge research. Even technologies that other countries have implemented better, like mobile payments and ride-sharing, were developed here. None of this denies the real problems that America faces, nor does it deny dominance in niche areas that European or Asian countries can boast of, but it does make the United States a uniquely valuable nation, one whose twin democratic and technological values are worth preserving. Patriotism means recognizing these special qualities and fighting for them.

Secondly, patriotism does not equal nationalism: as Charles de Gaulle once said, patriotism is when you love your country; nationalism is when you hate other countries. Patriotism should not be the exclusive domain of any political party or belief; it should belong to all. This fact is especially important because if one side cedes patriotism to the other because they think it’s exclusively the domain of xenophobic nativists, it leaves the way open for only xenophobic nativists to claim the label (as the saying goes, if you think that only fascists guard borders, then only fascists will guard borders). Patriotism simply stacks loyalty by priority, a priority that finds expression in the principles of evolutionary biology. The reason global affiliation is much harder to drive home than local affiliation is because kinship by virtue of family, community and country is much stronger and therefore easier to grasp than kinship to a large, fuzzy entity titled “the world”. You also cannot take care of the world if you first don’t take care of your own country.

If Americans don’t fight for America’s unique qualities because of a distorted view of patriotism, it will become a self-fulfilling prophecy. It will lead to a sclerotic young generation which does not work for the country because of ill-defined ideals. And whether Americans think being patriotic about their country is important or not, they can bet that citizens of other countries like China, India and Japan certainly feel patriotic about their own nations. You strive for what you believe in and help it grow and improve; if you don’t believe in your country and work to shore up its unique values, you actively hasten its death on the vine.

In particular, as a scientist I believe that patriotism as a whole must translate into the kind of scientific patriotism displayed by the emigre scientists of the 1930 and 40s. There were a few qualities they displayed that we should imbibe.

First and foremost, they believed that American science and education are worth preserving and advancing to their fullest extent possible. They not only made pioneering discoveries but spent an unusual amount of time teaching and training the next generation, fully recognizing that their scientific expertise would not amount to much in the long term if it’s not passed on to the next generation. Many of their students now occupy high positions in academia and industry and have made it possible to preserve American technological dominance.

Second, they saw past partisan politics, firmly believing that science and technology should transcend political differences. This was of course a more general feature of society that time, but it’s one that we sorely need to resurrect. Science knows no political masters or servants and can work for all.

Third, while they worked ceaselessly to improve the well-being of their country, these scientists realized that America is a global leader but has to lead without coercion, make its bounty available to other nations, be a role model for countries wanting to pursue scientific and democratic ideals. “America first” for them did not translate to “Everyone else last.”

Fourth, they continued the tradition of having America be a land of opportunity for people around the world. In many ways, the United States’s status as an immigrant-friendly country par excellence is still what uniquely distinguishes it from other countries; it is impossible to imagine China, for instance, to be a center of global immigration anytime soon. The joke that is often cracked, only half-jokingly, is that America won World War 2 because our Germans were better than their Germans. “Our Germans”, emigres like Bethe and Weisskopf, trained students from England, India, China and Australia, many of whom stayed here. We must continue to ensure that we are a welcome haven for others, most notably countries which we consider to be our adversaries. Our Chinese should be better than their Chinese.

Fifth, they never apologized for working on national security and defense. Even more fundamentally, they believed that the United States is a unique country whose borders and values are worth defending and which faces bonafide threats and challenges, including countries and groups that want to actively harm it. Of course, they also made sure to criticize bad ideas, as Bethe and his colleagues did in a paper criticizing Ronald Reagan’s “Star Wars”, but critiques of specific ideas had nothing to do with the basic belief in a strong national defense. In fact, one can make the argument that weeding out bad ideas is an essential feature, not a bug, of improving national security. Some of the scientists served on presidential advisory committees, many others served on JASON, a high-level advisory of scientists for the U.S. government that shoots down bad defense ideas and endorses good ones.

Another important lesson these scientists embodied, also critical in our times, was to remain friends and cordial colleagues even when vehemently disagreeing. For instance, Hans Bethe fell out in a major way with Edward Teller over the development of the hydrogen bomb and Teller’s testimony against Robert Oppenheimer. But while their relationship was never the same that it was before, you find them in their archives and letters working together on important topics like nuclear power, helping each other’s students when needed and even consulting at each other’s laboratories. These scientists never harbored the pernicious belief that disagreement equates disloyalty.

Lastly and most importantly, these scientists were grateful. Perhaps as immigrants they realized more than others that America had given them refuge from the ghosts and demons of their past, that it had provided them stability amidst chaos. They recognized that even with its problems, the American experiment is wholly unique, that it has given much to the world that needs to be preserved for as long as possible. I should know; as an immigrant scientist who came here more than twenty years ago, I am grateful to this country for providing me with not just the practical benefits of education, stability and economic opportunity but for the love, respect and inspired leadership of its people, qualities which I hope I can repay at least to some extent. My father admired FDR and Eisenhower, my mother George Washington Carver. Remember these men, they said, men who made America a great country.

In an age of globalization, fractured politics and a general belief that any exhortation of “country first” means embracing mindless jingoism, it is more important than ever for this country’s scientists and engineers to embrace scientific patriotism. With this in mind, it’s worth charting what could be called a “patriot’s manifesto” for America’s scientists and engineers:

We need to believe, as Kennedy and the scientists and engineers of the 1960s did, that America can build and do anything, both in the public and the private sectors. Even by 2023’s scientific standards the moon landing stuns our imagination and beggars belief. We can and should do things like it again. And again.

We should bring a scientist’s skepticism to ideas that we find irrational or ill thought out, but we should not let skepticism morph into cynicism. The cure for hype is not pessimism, it’s rational optimism. And we should never, ever let skepticism morph into the self-fulfilling prophecy of fatalism.

We need to work in areas like defense and national security without apologies, across political divisions. We should always believe that defending our country is important, just like people around the world believe that defending their own countries is important. We should always strive for peace, but that peace should be based on technological strength.

We need to keep welcoming talented people from across the world, giving them incentives to become American citizens and setting up a constant, renewing cycle of new minds and ideas.

We also need to freely borrow from the best that other countries have to offer, in a give-and-take informed in equal part by self-interest and global interest, recognizing that no country by itself can solve the great challenges that the world is facing. American progress is singularly important and can lead the way, but it is not and should not be a zero-sum game.

We need to understand that upholding the free exchange of ideas, even and especially unpopular ones, is inseparable from upholding democratic ideals like free speech. There should always be room for disagreement without judgment. The free American has always been the argumentative American.

We need to appreciate that in spite of recent developments, America through its values and attractions still commands the attention and respect of millions, including millions who will – and do – give anything to come here, and we need to acknowledge that we can continue to play a major leadership role in the world.

Most importantly, as von Neumann and Bethe did, and as Kennedy exhorted, we have to come together as Americans and believe that our uniquely American values are worth preserving and protecting. We have to affirm, as Bethe told Sommerfeld, “what we love about America”, and ask, as Kennedy said, “what we can do for our country and not what our country can do for us.” In that direction lies our more perfect union, and a better world for all.