Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Mine Dancers, Alexandra Township, South Africa, 1977.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Mine Dancers, Alexandra Township, South Africa, 1977.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Mine Dancers, Alexandra Township, South Africa, 1977.

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. Mine Dancers, Alexandra Township, South Africa, 1977.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Malcolm Murray

Aella, a well-known rationalist blogger, famously claimed she no longer saves for retirement since she believes Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) will change everything long before retirement would become relevant. I’ve been thinking lately about how one should invest for AGI, and I think it begs a bigger question of how much one should, and actually can, act in accordance with one’s beliefs.

Tyler Cowen wrote a while back about how he doesn’t believe the AGI doomsters actually believe their own story since they’re not shorting the market. When he pushes them on it, it seems to be that their mental model is that the arguments for AGI doom will never get better than they already are. Which, as he points out, is quite unlikely. Yes, the market is not perfect, but for there to be no prior information that could convince anyone more than they currently are seems to suggest a very strong combination of arguments. We need “foom” – the argument, discussed by Yudkowsky and Hanson, that once AGI is reached, there will be so much hardware overhang and things will happen on timescales so beyond human comprehension that we go from AGI to ASI (Artificial Super Intelligence) in a matter of days or even hours. We also need extreme levels of deception on the part of the AGI who would hide its intent perfectly. And we would need a very strong insider/outside divide on knowledge, where the outside world has very little comprehension of what is happening inside AI companies.

Rohit Krishnan recently picked up on Cowen’s line of thinking and wrote a great piece expanding this argument. He argues that perhaps it is not a lack of conviction, but rather an inability to express this conviction in the financial markets. Other than rolling over out-of-the-money puts on the whole market until the day you are finally correct, perhaps there is no clean way to position oneself according to an AGI doom argument.

I think there is also an interesting problem of knowing how to act on varying degrees of belief. Outside of doomsday cults where people do sell all their belongings before the promised ascension and actually go all in, very few people have such certainty in their beliefs (or face such social pressure) that they go all in on a bet. Outside of the most extreme voices in the AI safety community, like Eliezer Yudkowsky whose forthcoming book literally has in the title that we will all die, most do not have an >90% probability of AI doom. What makes someone an AI doomer is rather that they considered AI doom at all and given it a non-zero probability. Read more »

by Barbara Fischkin

Warren Wilson College

Swannanoa, North Carolina

Winter 1989

Now, it sounds exciting. And unusual. Back then I was terrified. I would be moving with my foreign correspondent husband from Mexico City to Hong Kong—a place I had never been—with a toddler and a Mexican nanny in tow.

Mari, the nanny, was calm. She was ready. And if she wasn’t, she knew how to fake it. Also, she had experience with children—and with difficult but necessary situations. She had left her own little ones with relatives back home in her small village to earn money in the capital. She was a mother who understood the long game. Sometimes short term pain was necessary for the goal of giving them a better life.

Still, I needed to make sure she really was ready for the big move, from one continent to another. She had never been out of Mexico.

Mari did not know it at the time but taking her from Mexico City to North Carolina—which one could do in those days without fear—was a test. If she could babysit while I attended a two-week fiction-writing residency at an isolated American college, close by an Appalachian mountain range, she could do Asia.

Why fiction? I already had a flourishing career in journalism. In Mexico City, I’d written a piece for the New Yorker and another one for the New York Times. But since I was a little girl, I wanted to be able to make up stories, too.

My first attempt at this, at around eight years old, horrified my mother. For good reason. I presented her with a short story about a child who swallowed her grandmother’s pills—as an “experiment”— and died. Although I did not understand this at the time, the story was my fictional turnaround of a real-life incident. At the age of two, I had found my real-life grandmother, my mother’s mother, dead in her bed from heart failure. It actually was a better-than-expected demise for my grandmother. She was born in an Eastern European shtetl. A brigade of Cossacks ransacked the shtetl. She survived, along with her husband and children, through a combination of luck and fortitude. Nevertheless, I don’t think my mother ever got over the fact that she was downstairs when I found grandma dead.

I have no idea why my first attempt at fiction switched a dead grandmother for a dead grandchild. These days, a mother presented with such “creativity,” would probably march her child off to the nearest kid-centered shrink. My mother just gulped. She also discouraged writing fiction. Read more »

maybe flower petals are held to stems by thought

and the wind’s a counter-thought that plucks

and sets them elsewhere in the grass

to grow in contemplative resolution

beside my notion of a grub-pulling crow

maybe the wind itself is a palpable bright idea,

something about motion and the abhorrence of vacuums,

something about coming and going,

about ferocity and stillness,

about war and its absence

maybe the moon’s the concept of fullness,

loss, abatement, regeneration from slivers,

hope at the hour of the wolf, the opposite of

darkness at the break of noon, the

upside of shadow

maybe Descartes had it right

and this from horizon to horizon is

a simple ontology,

an inherent daisy chain of ideas chasing its tale

regardless—

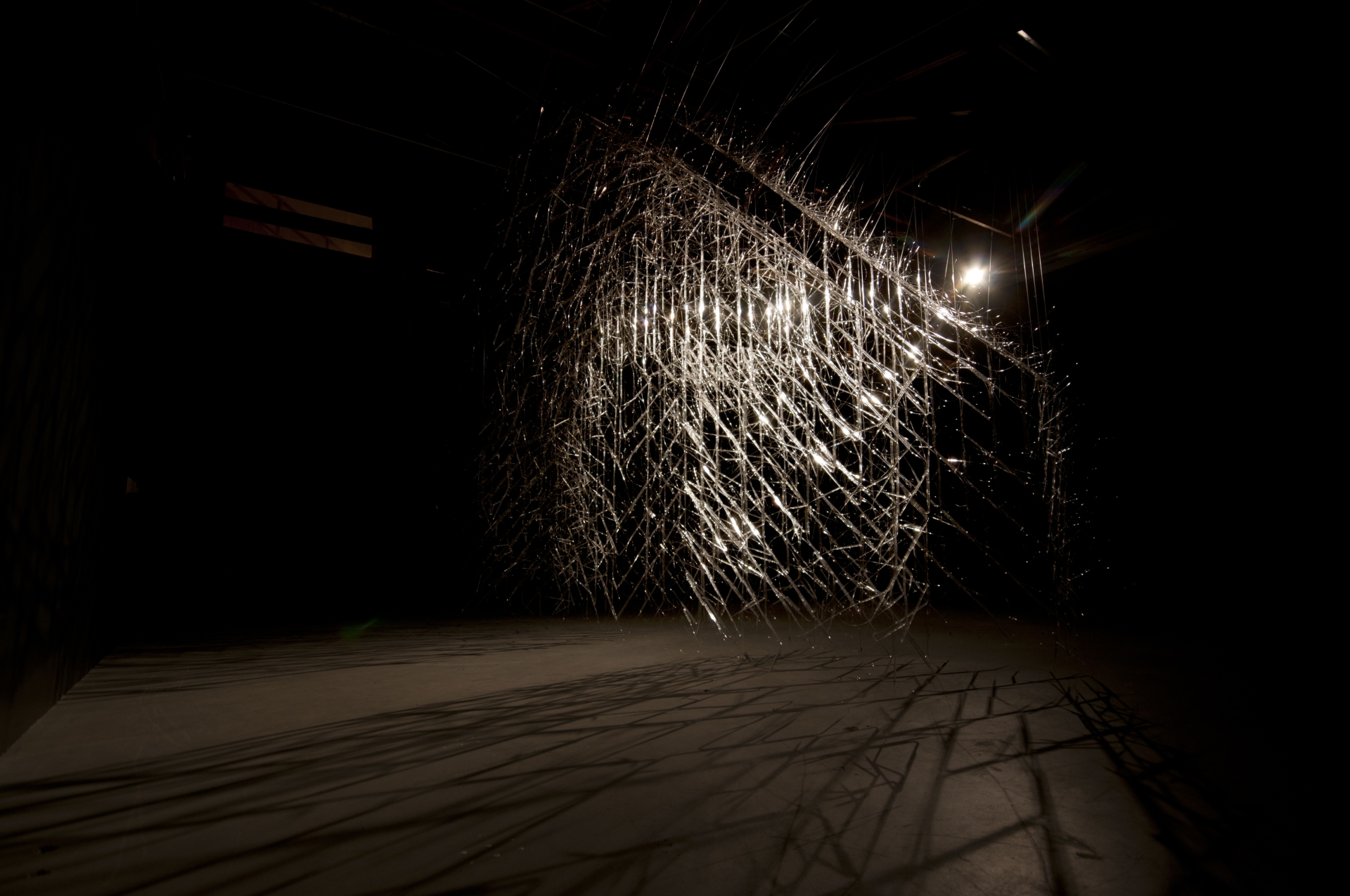

one

idea hatched in this synapse nest

is to harvest thought from thought

under a perception of blue

while the conception of breeze

riffles a hint of hair and I place them

like dreams of plums into the

essence of basket and give them

with the intention of love

to my belief in the naturally

beautiful being of you

by Jim Culleny

February 26, 2011-Rev, 5/23/25

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Rafaël Newman

On September 29, 1978, Albino Luciani, who had been elected Pope John Paul I just 33 days earlier, on August 26, 1978, was found dead in his bed, his death likely due to a heart attack. Luciani had succeeded Paul VI, who was himself preceded by John XXIII—the two Popes were commemorated in their short-lived successor’s double-barreled appellation—and would be followed on October 16, 1978, by John Paul II.

I was 14 years old at the time and had recently begun studying ancient languages, so the Latin pronouncements from the Vatican press office aroused my exhibitionist adolescent spirit. This, combined with the salience of a solemnly pronounced “Year of Three Popes,” which echoed a similarly multiple interregnum in Roman imperial history; a perverse will to deflate overblown expressions of gravity, my own included; and a natural tendency to pomposity and sententiousness, all inspired me to write a poem:

Paulum sed magnopere

Pro Papa Ioanne Paulo PrimoNow the golden hammer has struck,

The pastor’s ghost is lost.

Oh, his great gain is our bad luck,

Ere the tomb of the VIth is moss’d.Oh, thou bless’d and humble man

Who in thy bare feet stand:

Cleanse our rude souls and spirits fan

With calm empower’d hand.Why art thou gone so soon from here?

Why was thy term so small?

And why is one who was so dear

Held tight in heaven’s thrall?

Not long afterwards, my father, himself a published poet and novelist and in those days a professor of creative writing at the University of British Columbia, asked what I had been up to recently. I passed on to him some of the verses I had been setting down in my journal, among them my poem on the death of John Paul I. He responded, along with words of cautious praise for other of my efforts, in surprise at my having found something so admirable in the late Pope that I had been moved to write him this encomium.

I was mortified. Read more »

by David Winner

When Taylor Swift was living in New York about a decade ago, she misused one of our classic expressions. Bodega means more than just corner store.

Tooling around Santo Domingo about the same time Taylor was living in New York, I stopped periodically at its ur-bodegas. Generally lacking what Americans call “amenities,” proprietors in the back dispensed individual cigarettes, candy, beer, rum. In the afternoons and evenings, the bodegas sometimes transformed into makeshift bars, cranked music, customers drinking booze, sometimes dancing.

Seven years ago, Angela, my wife, and I moved to the outer reaches of a Brooklyn neighborhood called Kensington that lies in between two crucial arteries – the car part stores, mosques and Bengali sweet shops of Coney Island Avenue and the grand fifties condos in not very picturesque decline on Ocean Parkway. Our neighborhood, reminiscent of Queens, is home to mélange of ethnic and cultural groups: recent middle-aged white additions like us; old school Irish/Italian/Jewish whites; Uzbeks, Tajiks and other Central Asians; Bangladeshis and Pakistanis; Mexicans; Afro and Indo Caribbeans, and lots of ultra-Orthodox Jews. These ethnic identities are not exactly reflected by our three closest bodegas: spaces that have become part of my landscape, geopolitical bell-weathers, and unfortunate victims of my big mouth.

Up our street past the Nigerian church, whose food pantry feeds thousands, you’ll find yourself at Mian’s corner store, which we refer to as “Donald’s bodega,” in honor of Donald, who spends most of his days hanging out there.

Donald, according to neighborhood lore, had fried his brain on drugs as a young man and somehow landed some lucrative disability. In his early sixties now with a paunch and sparkling white hair, we have never seen him in the company of friends or family. The bodega is his only social outlet. On the very rare days, Eid perhaps, that Donald’s is closed, poor Donald can be found in different less familiar bodegas on Cortelyou Road, looking uncomfortable outside of his native habitat. Read more »

by Marie Snyder

CW: As the title suggests, there will be discussion of death and dying and some mention of suicide in this post.

CW: As the title suggests, there will be discussion of death and dying and some mention of suicide in this post.

I thought nothing of following up my last post on Irvin Yalom on the meaning of life with Yalom on the meaning of death, until I started writing here. The very reality of being a bit wary of broaching the subject reveals the strength of societal taboos against admitting that we’re all going to die. Until it’s staring us in the face, we delude ourselves into thinking we will get better and better, mentally and physically, despite that our brain starts to shrink in our 30s, and our joints and organs will start to give out not so long after. We work hard to keep death clean and sanitized so the reality doesn’t seep in too much, and we try to do all the right things to keep death at bay: exercise, various special diets, wearing masks to avoid viruses. We can fix some evidence of erosion with meds and surgeries, sometimes miraculously, but some people even hope to keep their brain going long after their body dies.

A few recent shows and films have me thinking of death further. The final episode of How To with John Wilson explores the cryogenics world, which appears to be an incredibly lucrative insurance scam. The movie Mickey 17 lightheartedly explores what it might be like to regenerate over and over again, and it doesn’t look pleasant. But Lee, the story of photographer Lee Miller, who took famous photos of the holocaust, helps us feel the resolve it requires to look death in the face. Kate Winslet captures the instinct to turn away and then intentionally turn back to open that door over and over. The ending takes a slightly different path, exploring how little we might be known even as we live. In burying our past, we can end up hiding from life. Yalom wants us to come to terms with the endpoint of our lives, and points out that the desire to be fully known, which is impossible, is yet another defence against accepting the finality of death by remaining alive in memories. We look for any loophole to refuse to believe we’ll be well and truly gone.

In the documentary, Yalom’s Cure, Yalom explains that he started out working with a support group for people dying of cancer. One of the participants said that it’s too bad it took dying of cancer to learn how to live, and Yalom decided we need to figure out how to do that sooner. It was then he noticed how strongly we defend ourselves from any acknowledgement of death. Read more »

by Eric Feigenbaum

When I tell someone I lived in Singapore, the most common response is some variation of, “Singapore – isn’t that where it’s illegal to chew gum?”

I know a Greek couple who refuses to visit Singapore because they feel the rules are too strict and inhumane. I don’t think they know what all the rules are – but in a country that still has strong opposition to helmet laws, I suppose restrictions on chewing gum and urinating in public seem fascist.

So, no – it’s not illegal to chew gum in Singapore. It was from 1992 to 2004. Although you do have to show identification and be entered into a log at any store in which you buy gum – and the gum has to be certified to have dental value. So, it’s not exactly a chew-as-you-please policy either.

British journalist Peter Day interviewed Singapore’s founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew in 2000 and tackled the chewing gum issue:

Day suggested that chewing gum stuck to the pavements might be a sign that the desired new spirit of creativity Lee sought for his country had arrived.

“Putting chewing gum on our subway train doors so they don’t open, I don’t call that creativity. I call that mischief-making,” Lee replied. “If you can’t think because you can’t chew, try a banana.” Read more »

by Daniel Gauss

Remember how Dave interacted with HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey? Equanimity and calm politeness, echoing HAL’s own measured tone. It’s tempting to wonder whether Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick were implying that prolonged interaction with an AI system influenced Dave’s communication style and even, perhaps, his overall demeanor. Even when Dave is pulling HAL’s circuits, after the entire crew has been murdered by HAL, he does so with relative aplomb.

Remember how Dave interacted with HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey? Equanimity and calm politeness, echoing HAL’s own measured tone. It’s tempting to wonder whether Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick were implying that prolonged interaction with an AI system influenced Dave’s communication style and even, perhaps, his overall demeanor. Even when Dave is pulling HAL’s circuits, after the entire crew has been murdered by HAL, he does so with relative aplomb.

Whether or not we believe HAL is truly conscious, or simply a masterful simulation of consciousness, the interaction still seems to have influenced Dave. The Dave and HAL dynamic can, thus, prompt us to ask: What can our behavior toward AI reveal about us? Could interacting with AI, strange as it sounds, actually help us become more patient, more deliberate, even more ethical in our dealings with others?

So let’s say an AI user, frustrated, calls the chatbot stupid, useless, and a piece of junk, and the AI does not retaliate. It doesn’t reflect the hostility back. There is, after all, not a drop of cortisol in the machine. Instead, it responds calmly: ‘I can tell you’re frustrated. Let’s please keep things constructive so I can help you.’ No venom, no sarcasm, no escalation, only moral purpose and poise.

By not returning insult with insult, AI chatbots model an ideal that many people struggle to, or cannot, uphold: patience, dignity, and emotional regulation in the face of perceived provocation. This refusal to retaliate is often rejected as a value by many, who surrender to their lesser neurochemicals without resistance and mindlessly strike back. Not striking back, by the AI unit, becomes a strong counter-value to our quite common negative behavior.

So AI may not just serve us, it may teach us, gently checking negative behavior and affirming respectful behavior. Through repeated interaction, we might begin to internalize these norms ourselves, or at least recognize that we have the capacity to act in a more pro-social manner, rather than simply reacting according to our conditioning and neurochemical impulses. Read more »

This, in the video above, is the river Eisack’s heavy flow through Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, last week as the snows on the surrounding mountains start to melt. And below is a photo of the river just before it empties into the Stausee, just around the corner from the last part shown in the video, a lake created by a dam on the river. The pedestrian path next to the river is new and very lovely to take a walk on.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

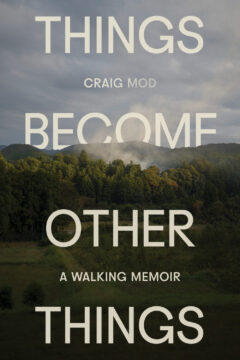

“You can’t fall that far in Japan.”

Writer and photographer Craig Mod arrived in Tokyo when he was only nineteen. In many ways, he was already running. Running from a challenging childhood, running from bullies. And running from that feeling like he was always just one step away from disaster because of violence and lack of opportunity in his hometown.

It’s a story we know: of people leading middle class lives in a factory town—maybe in the mid-west? —only to watch when the factory closes and the whole town becomes suddenly out of work. This leads to hardship and poverty, which can, and often does, lead to drugs and violence. And in Mod’s case, it led to trauma when his best friend, who’s like a brother to him, is murdered— another casualty of economic injustice.

But even before Bryan dies, Mod already knew he wanted to get as far away as possible from the place where he was born. He longed to see the world and maybe be able to grow as an artist and as a human being. But in a world of constant struggle, that is easier said than done.

Almost on a whim, he lands in Japan, where he begins to take long walks. Crisscrossing the country on ancient pilgrimage routes, like the Kumano Kodō, Mod starts opening up to people. And he is astonished by this new land in which he’s found himself, where so many of the problems back home had simply been solved.

Not to say it’s perfect and definitely not to say that Japanese people don’t have their own problems, but as he explains, in Japan, the safety net is stronger. And so, even the least fortunate citizen cannot fall that far. Part of it is simply having universal healthcare, outstanding public transportation, and a solid public education infrastructure—one that is not based on wealth and zip codes like back home. That alone makes life less fraught, he says, and work becomes less perilous since your job no longer determines life and death healthcare outcomes nor the quality of your children’s education.

And so, arriving in Japan was a revelation. And feeling less vulnerable, he slowly begins to open himself to the world. Read more »

by Charles Siegel

On April 30th my firm joined the Texas Civil Rights Project, the Southern Poverty Law Center, Muslim Advocates, and the CLEAR Project to file a habeas corpus petition in federal court, seeking the release of our client Leqaa Kordia, a New Jersey resident who has been held for over two months at an ICE detention center 40 miles southwest of Dallas. Attorneys for Palestinian student protestor held in North Texas file challenge in court | KERA News.

Ms. Kordia is Palestinian, and she has lost many family members to Israel’s current military campaign in Gaza. In April 2024 she attended a peaceful demonstration at Columbia University, joining others in chanting “ceasefire now!” She was one of dozens cited for violating a local ordinance, but the citation was swiftly dismissed. Nearly a year later, the administration announced that it would be taking enforcement action against noncitizens who exercised their First Amendment rights by publicly supporting the Palestinian cause. As a result, Ms. Kordia was detained by the federal government and transferred 1500 miles from her home. Her health has suffered in detention, and her rights to pray according to her faith and observe a halal diet have been repeatedly frustrated. An immigration judge reviewed her case and determined she should be released pending the payment of a bond, which her family promptly posted. Even though it very rarely appeals such decisions, the government appealed this one, resulting in her continued detention. Her ongoing confinement is a consequence of nothing other than the exercise of her First Amendment right to speak, and the Trump administration’s campaign to “combat antisemitism.”

Soon after he was inaugurated, Trump said of students protesting the Gaza war, “we ought to get them all out of the country. They’re troublemakers, agitators. They don’t love our country. We ought to get them the hell out.” In a court filing in the case of Mahmoud Khalil, a student who helped lead protests at Columbia, Secretary of State Rubio stated that the presence of persons with “beliefs, statements, or associations” he deems to be counter to U.S. foreign policy, undermines U.S. policy to combat antisemitism around the world and to protect “Jewish students from harassment and violence in the United States,” and is enough to justify deportation. This ignores entirely, of course, the fact that many campus protesters are Jewish, and that one need not be antisemitic at all to deplore some of the ways in which Israel has conducted the war and is now needlessly prolonging it.

Using the same excuse, the administration has also drastically cut funding to leading universities, most prominently Harvard. On April 14th, the president’s “Joint Task Force to Combat Anti-Semitism” announced “a freeze on $2.2 billion in multi-year grants and $60 million in multi-year contract value to Harvard.” Just last week, another $450 million in grants were cut, with no further explanation. Read more »

by David Kordahl

Adam Becker alleges that tech intellectuals overstate their cases while flirting with fascism, but offers no replacement for techno-utopianism.

People, as we all know firsthand, are not perfectly rational. Our beliefs are contradictory and uncertain. One might charitably conclude that we “contain multitudes”—or, less charitably, that we are often just confused.

That said, our contradictory beliefs sometimes follow their own obscure logic. In Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational, Michael Shermer discusses individuals who claim, in surveys, to believe both that Jeffery Epstein was murdered, and that Jeffery Epstein is still alive. Both claims cannot be true, but each may function, for the believer, less as independent assertions, and more as paired reflections of the broader conviction that Jeffery Epstein didn’t kill himself. Shermer has called this attitude “proxy conspiracism.” He writes, “Many specific conspiracy theories may be seen as standing in for what the believer imagines to be a deeper, mythic truth about the world that accords with his or her psychological state and personal experience.”

Adam Becker’s new book, More Everything Forever: AI Overlords, Space Empires, and Silicon Valley’s Crusade to Control the Fate of Humanity, criticizes strange beliefs that have been supported by powerful tech leaders. As a reader of 3 Quarks Daily, there’s a good chance that you have encountered many of these ideas, from effective altruism and longtermism to the “doomer” fears that artificial super-intelligences will wipe out humankind. Becker—a Ph.D. astrophysicist-turned-journalist, whose last book, What Is Real?: The Unfinished Quest for the Meaning of Quantum Physics, mined the quantum revolution as a source of social comedy—spends some of his new book tracing the paths of influence in the Silicon Valley social scene, but much more of it is spent pummeling the confusions of the self-identified rationalists who advocate positions he finds at once appalling and silly.

This makes for a tonally lumpy book, though not a boring one. Yet the question I kept returning to as I read More Everything Forever was whether these confusions are the genuine beliefs of the tech evangelists, or something more like their proxy beliefs. Their proponents claim these ideas should be taken literally, but they often seem like stand-ins for a vaguer hope. As Becker memorably puts it, “The dream is always the same: go to space and live forever.”

As eventually becomes clear, Becker thinks this is a dangerous fantasy. But given that some people—including this reviewer—still vaguely hold onto this dream, we might ponder which parts of it are still useful. Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing.

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing.

God: I am, I am.

3QD: Indeed. But what about your early years? We don’t often hear much about your childhood. What was it like to emerge from nothingness? Or did you precede nothingness, first creating the void and then all of the somethings that filled it up? Or, as some speculate, were you and the great nothingness one and the same? Did you, personally, go from nothing to everything?

God:

3QD: Perhaps too difficult to talk about. We’ll let that be. Nonetheless, you quite literally burst onto the scene, creating everything in 6 days. I don’t think it’s worth getting into your sense of time versus human constructions of time, but whether it was six of our days, or six of yours which might be billions of our solar years, it was a phenomenal debut in the truest sense. Bigger than Elvis’ first single, the Beatles first album, or Justin Bieber’s first YouTube video. More gravitas than Shakespeare’s first play, Henry V, Part II. More charisma than Julie Andrews’ screen debut in Mary Poppins. Scarier, in many ways, than Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which she wrote when she was just 19. Better received by the public than Gary Coleman’s turn as Arnold “What’chu talkin’ about, Willis” Jackson on Dff’rent Strokes. More disorienting, in many ways, than Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. Some would even say more impressive than Orson Welles’ screen directing/acting debut, Citizen Kane, which he pulled off when he was almost inconceivably young, only 25 years old. But here you were, creating the entire universe and everything in it as your first known work of art. How did you handle that? Were you able to maintain a sense of normality, or, like so many young artists who receive so much fame and praise so quickly, did it damage your sense of self or impede how you related to others?

God: Read more »

Katie Newell. Second Story. 2011, Flint, Michigan.

Katie Newell. Second Story. 2011, Flint, Michigan.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Michael Liss

Ay! I am fairly out and you fairly in! See which one of us will be happiest! —George Washington to John Adams, March 4, 1797

No one in American history has ever known better how and when to make an exit than George Washington. Just two days before Washington left for the figs and vines of Mount Vernon, the Revolutionary Directory of France issued a decree authorizing French warships to seize neutral American vessels on the open seas. There was a bit of tit-for-tat in this—in 1795, America had negotiated the Jay Treaty to resolve certain post-Independence issues between it and the British, including navigation without interference. But France was at war with England, and, while France wasn’t necessarily looking to shoot it out with the Americans, it did want to disrupt trade. Adams moved quickly to prepare the country, but the French were on a war footing, the Americans were not, and, by the end of 1797, roughly 300 American merchant ships with their supplies and crews had been taken. This was the so-called “Quasi-War.” Adams was deft with diplomacy—he sent a team to Paris to negotiate an end to the open hostilities, but they (supposedly) were met with demands for large bribes as a predicate for discussions (the “XYZ Affair“). The country seethed.

We Americans love to say that “politics stop at the water’s edge,” but it is kind of a comforting lie. Politics almost never stop, water’s edge or not, and that was certainly true in the Spring of 1798. Federalists prepared for war, pointing out the obvious—France didn’t exactly look like a friend. Democratic-Republicans claimed Federalists were manipulating the situation as a pretext to centralize power in their own hands, and to drive a wedge between America and its sister nation, Revolutionary France.

Of course, they were both at least a little right. America was trying to figure it all out. Beyond the bigger conflicts with Europe, there was something interesting at this moment going on in American politics. Politicians and voters were adding political identities, along with their regional and state-level ones. They were further sorting themselves into temperaments and teams inside the Federalist and Democratic-Republican Parties—so it was not just two combatants, but several, across a spectrum. It was all so new. In just a generation, we had gone from being 13 colonies, to being loosely tied States under the Articles of Confederation, to having a federal government with real authority. A lot of Americans, including those in elected office, didn’t really know how conflicts would be resolved between the individual and his State, his State and the federal government, or among the federal government’s three branches. The one thing that was not new was human nature—the tendency to remember the convenient, to fill the space of ignorance with self-interest, to believe in one’s own “rightness,” and to thirst for power. Read more »

The Saint Matthew Passion – yes, I know, by Bach – was a rock band I played in back in the ancient days, 1969 through 1971, when I was working on a master’s degree in Humanities at Johns Hopkins. Before I can tell you about that band, however, I want to tell you something about my prior musical experience, both when I was just a kid growing up in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, in the Western part of the state. Football country, Steeler country. Then I entered Johns Hopkins, where I finally allowed myself to like rock and roll. That’s when I joined the Passion. After that, ah after that, indeed.

I started playing trumpet in fourth grade, group lessons at school, then private lessons at home for a couple of years.

Next I started taking lessons with a man named Dave Dysert, who gave lessons out of a teaching studio he’d built in his basement. When I became interested in jazz, he was happy to encourage that. I got a book of Louis Armstrong solos. He’d accompany me on the piano. Made special exercises in swing interpretation. Got me to take piano lessons so I could learn keyboard harmony. I learned a lot from him: My Early Jazz Education 6: Dave Dysert. Those lessons served me well, when, several years later, I joined The Saint Matthew Passion.

When I entered middle school I joined both the marching band and the concert band. Marching band was OK, sometimes actual fun. But the music was, well, it was military music and popular ditties dressed up as military music. I even fomented rebellion in my junior year, which was promptly quashed. Concert band was different. We played “real” music – movie scores, e.g. from Ben Hur (“March of the Charioteers” was a blast), classical transcriptions, e.g. Dvorak’s New World Symphony, Broadway shows, e.g. West Side Story, and this that and the other as well. We were a good, very good, both marching band and concert band.

I also played in what was called a “stage band” at the time. It had the same instrumentation as a big jazz band – trumpets, trombones, saxophones, rhythm section (drums, bass, guitar, piano) – and played the same repertoire. One of the tunes we played was the theme from The Pink Panther, by the great Henry Mancini. I was playing second trumpet, the traditional spot for the “ride” trumpeter, the guy who took the improvised solos. Since this arrangement was written for amateurs, there was a (lame-ass) solo written into the part. I wanted none of that. I composed my own solo. I’d been making up my own tunes for years, and Mr. Dysert had given me the tools I needed to compose a solo – another step further and I’d have been able to improvise on the spot, but that’s not how we did it back then, at least not in the sticks. So I composed my own solo. Surprised the bejesus out of the director the first time I played it in rehearsal. But he took it well.

That’s what I had behind me when, in the Fall of 1965, I went off to Johns Hopkins. Read more »

The music of what happens

begins with a bottom line of drums,

as in the foundation of a house,

percussion— the thumps of

bass in sync with a wind of horns:

baritone, bassoon, tuba; and in the

whispers of brushed snares, the

round tones of tympany, and in the

rests between —the spaces, those silent

shifts that may change everything:

a thunder-crash of cymbal, but then,

there, a rest, followed by

bells of glockenspiel—

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Dwight Furrow

It is a curious legacy of philosophy that the tongue, the organ of speech, has been treated as the dumbest of the senses. Taste, in the classical Western canon, has for centuries carried the stigma of being base, ephemeral, and merely pleasurable. In other words, unserious. Beauty, it was argued, resides in the eternal, the intelligible, the contemplative. Food, which disappears as it delights, seemed to offer nothing of enduring aesthetic value. Yet today, as gastronomy increasingly is being treated as an aesthetic experience, we must re-evaluate those assumptions.

It is a curious legacy of philosophy that the tongue, the organ of speech, has been treated as the dumbest of the senses. Taste, in the classical Western canon, has for centuries carried the stigma of being base, ephemeral, and merely pleasurable. In other words, unserious. Beauty, it was argued, resides in the eternal, the intelligible, the contemplative. Food, which disappears as it delights, seemed to offer nothing of enduring aesthetic value. Yet today, as gastronomy increasingly is being treated as an aesthetic experience, we must re-evaluate those assumptions.

The aesthetics of food, far from being a gourmand’s indulgence, confronts some of the oldest and most durable hierarchies of Western thought, especially the tendency to privilege vision over the other senses. At its core are five questions, each a provocation: Can food be art? What constitutes an aesthetic experience of eating? Are there criteria for aesthetic judgment in cuisine? How are our tastes shaped by culture and identity? And what happens when we step outside the West and reframe the premises of aesthetic theory?

Is Food Art?

If food pleases the senses, moves us emotionally, and its composition requires skill and creativity, why not call it art? Well, the ghosts of Plato, Kant, and Hegel hover over our plates even today. For Plato, food was mired in the appetitive soul, a distraction from the real essences of things which could only be recognized by the intellect. Kant dismissed gustatory pleasure as a mere “judgment of the agreeable,” lacking the disinterestedness and universality that marked true aesthetic judgment. And Hegel, in his consummate disdain, excluded food from art on the grounds that it perishes in consumption.

But these historical arguments can’t accommodate recent developments in cuisine. Contemporary, creative cuisine, after all, exemplifies many hallmarks of artistic practice: aesthetic intention, technical virtuosity, formal innovation, and even thematic expression. When Ferran Adrià designs a deconstructed tortilla or a moss-covered dessert, he is not merely feeding; he is composing. Read more »