by Jerry Cayford

It’s a book about how our political system fell into this downward spiral—a doom loop of toxic politics. It’s a story that requires thinking big—about the nature of political conflict, about broad changes in American society over many decades, and, most of all, about the failures of our political institutions. (2)

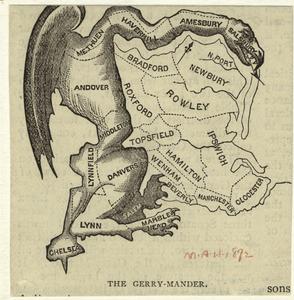

Where to begin fixing our dysfunctional society is about as contentious a question as there is. Lee Drutman’s 2020 book Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America confronts it head-on. Chapter 1, “What the Framers Got Right and What They Got Wrong,” goes straight to the heart of the matter: what the Founding Fathers got wrong is political parties. They understood the threat of tyranny that parties (“factions”) posed, but they misunderstood the benefits and inevitability of parties. They structured our government to discourage parties, instead of to accommodate them. As Drutman explains, those structural weaknesses have finally caught up with us in today’s toxic partisanship.

Like the Founders, Drutman gets important things right and wrong. He says, “At its core, my argument can be distilled into two words: institutions matter” (4). Political parties are the institutions he defends and criticizes. What we need parties to provide are substantive choices, not coercive conformity or destabilizing toxicity. This focus on parties is one of the many, many things Drutman gets right in his well-written, informative, and important book. When he turns from diagnosis to solution, though, he gets one big thing wrong. Read more »

The Supreme Court doesn’t play politics.

The Supreme Court doesn’t play politics.