by Rafaël Newman

When I was eleven years old, Eva Kornpointner, my mother’s mother—our Grossmutti, as we were taught to call her—took me, together with all five of her other grandchildren, on a trip up the Rhine. Our ultimate, trans-Rhenish objective, after we had crossed the Swiss border at Basel, was Zurich and its hinterland, where Grossmutti had been born in 1906 into a family of German immigrants to Switzerland; along the way we visited other sites of personal importance to her in Germany, such as Munich, where she briefly attended university in the 1930s and where our grandfather had been born, and Coburg, in Upper Franconia, where her ancestors, according to family legend, had helped to build the famous castle. We were confounded by the enormous, filthy Cologne Cathedral, admired the more congenial Mainzer Dom, and goggled at the “devil’s footprint” in the Münchner Frauenkirche, the legendary vestige of a metaphysical architectural dispute. (Churches figured prominently on Grossmutti’s itinerary: surprising, given her lifelong commitment to atheism and progressive politics, but inextricable from German history.)

In Switzerland, Grossmutti took us on a tour of the city of Bern, where we played chess with life-sized pieces on an outdoor board in the Rosengarten, Napoleon’s vantage point upon briefly occupying Switzerland, and sniffed wonderingly at what seemed to be chocolate-scented vapors emanating from manhole covers in the Altstadt. When we did finally arrive in Zurich we were treated to homemade plum tart by Fee Meyer, our mothers’ cousin and one of our last remaining local relatives. Fee also escorted us on a hike up the Uetliberg and a visit to the neighboring town of Rapperswil, the home of her aging mother, our great-aunt Käthe, Grossmutti’s eldest sister. Tante Käthe (whom her wizened aspect and lack of English, together with whispered family legend, had conspired to give a forbidding aura) had spent the war years in Germany, having returned to the family’s homeland in the 1930s along with one of her brothers; this latter had then stayed on, in what was to become East Germany, while Käthe and her daughter Fee made their way back to Switzerland in the late 1940s.

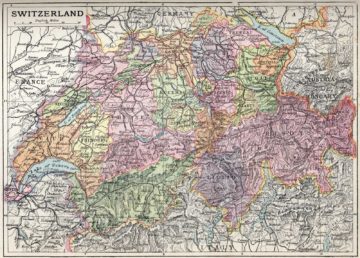

Now, it may have been a function of this German heritage of Grossmutti’s, and the fact that her own personal, historical experience of Switzerland (born in Baden, in the canton of Argovia, and raised near Winterthur, with family in Schwerzenbach, outside of Zurich) was exclusively of the Alemannic or Germanophone cantons of her adopted country—but it was not until long afterwards that I realized there even was another linguistic region of Switzerland. For indeed there is, a collection of Francophone cantons known collectively as “la Romandie” or “das Welschland,” each sobriquet in its own way a memento of the SPQR and home to just under a quarter of the Swiss population. (Never mind the two other Latinate cantons, Italophone Ticino and the Romansh-speaking parts of the Grisons, which came even later to my consciousness.) I did already know, in 1975, that there was a French-speaking city called Geneva, because one of my parents’ friends had left her husband in Vancouver to go and work there as an interpreter; and I was vaguely aware that the city had something to do with Switzerland. But I was uncomfortable thinking about the name, and even more so pronouncing it, inhibited in part by its gloomy personal associations with divorce and familial separation as well as, it occurs to me in retrospect, the fact that it was a near anagram for the word vagina, and thus taboo to the prepubescent mind. Nor could this lacuna in my political geography be accounted for by latent Francophobia, since our trip that summer had in fact begun in Paris, where my cousins, fluent French-speakers, lived with their parents, who were attached to the Canadian embassy there; and the whole family cultivated a worship of the French capital worthy of the Lost Generation.

Now, it may have been a function of this German heritage of Grossmutti’s, and the fact that her own personal, historical experience of Switzerland (born in Baden, in the canton of Argovia, and raised near Winterthur, with family in Schwerzenbach, outside of Zurich) was exclusively of the Alemannic or Germanophone cantons of her adopted country—but it was not until long afterwards that I realized there even was another linguistic region of Switzerland. For indeed there is, a collection of Francophone cantons known collectively as “la Romandie” or “das Welschland,” each sobriquet in its own way a memento of the SPQR and home to just under a quarter of the Swiss population. (Never mind the two other Latinate cantons, Italophone Ticino and the Romansh-speaking parts of the Grisons, which came even later to my consciousness.) I did already know, in 1975, that there was a French-speaking city called Geneva, because one of my parents’ friends had left her husband in Vancouver to go and work there as an interpreter; and I was vaguely aware that the city had something to do with Switzerland. But I was uncomfortable thinking about the name, and even more so pronouncing it, inhibited in part by its gloomy personal associations with divorce and familial separation as well as, it occurs to me in retrospect, the fact that it was a near anagram for the word vagina, and thus taboo to the prepubescent mind. Nor could this lacuna in my political geography be accounted for by latent Francophobia, since our trip that summer had in fact begun in Paris, where my cousins, fluent French-speakers, lived with their parents, who were attached to the Canadian embassy there; and the whole family cultivated a worship of the French capital worthy of the Lost Generation.

No, my obliviousness to the presence of a second important national language in Switzerland was in a sense symptomatic of the same malaise from which the country as a whole suffers, and which should have been familiar to me already as an Anglophone Canadian: the tendency of speakers of a majority language to overlook, downgrade, dismiss, or discount minority language speakers, and to behave as if their own language, because that of the majority, were in fact the sole “natural” national tongue. And in return to be resented and, albeit more deliberately, ignored by members of the linguistic minority.

In English-speaking Canada this phenomenon has been referred to as “two solitudes,” after the eponymous 1945 novel by the Maritime writer Hugh MacLennan. In Germanophone Switzerland, meanwhile, the (linguistic, political, cultural) gulf separating Romands from Dütschschwyzer is popularly known as the Röschtigraben, or Röschti (a grated and fried potato pancake) trench, after a dish eaten traditionally in rural German-speaking areas of Switzerland. The Hashbrown Divide.

In political terms, the divide between the two main linguistic regions of Switzerland is often manifested in a pronounced polarity in voting patterns, for instance when national referenda tend to return a majority right-wing result from the German side, and a majority left-wing result from the French side (although this difference is currently ceding, in the country as a whole, to a generalized divide between rural and urban regions, regardless of their linguistic makeup). More practically, and more familiarly to me from my youth in Canada, there is an institutionalized difficulty teaching each linguistic group the other’s language, with the German side favoring “early English” instruction in public schools over French, and the French side (understandably) divided over whether to teach their children “high” or “written” German, or to begin early on with the dialect version actually spoken on the other side of the country. (But then of course the question would be: which dialect—that of Bern, Zurich, Basel…?) I regularly attend meetings of a national organization that brings together members from both sides of the divide, at which the lingua franca, as often as not, turns out to be English.

*

On a recent rainy Sunday, I took a three-hour train ride, from Zurich by way of Lausanne to St-Maurice, in the canton of Valais on the border to the canton of Vaud, to hear my friend Annina Haug sing Rosina (brilliantly, and with considerable comedic chops) in Barbiere di Siviglia. The audience in the unexpectedly large auditorium, hidden two floors below street level in a non-descript municipal building, was large and boisterous, taking their time finding their seats, calling out to friends and neighbors, and, when the opera was underway, applauding long and enthusiastically after the overture, following particularly successful arias, and during the many curtain calls (and encore of the first-act finale!) that closed the performance. As I once heard a Francophone Swiss performer at the Zirkus Knie complain, following an attempt to get the uptight Zurich audience to sing along with him: “That’s the sort of spirit you get in Lausanne on a Monday morning!” Now here was that celebrated “Latin” spirit on a Sunday afternoon, and it was terrific.

After the intermission, but just before the curtain went up for the second act, I turned to the couple seated next to me—French-speakers, as most of the crowd seemed to be—and asked them whether they were from the Romandie (they were: or rather, she was, but he, although now resident with his wife there, came originally from Bern). And were they familiar with the term Röschtigraben? They certainly recognized it, they assured me, at least once I had repeated it in French (“le fossé des rösti”); and when I asked them to explain it to me, they said it was a shorthand for the difference between the Francophone and Germanophone regions of Switzerland.

“Politically, yes, I understand that,” I replied politely, “because the Dütschschwyzer tend to be more conservative than the Romands”—here they made a gesture of demurral, either to reject my perceived self-deprecation or to align themselves, against the cliché, with the political center—“but why does it mean that? I mean, who is it who eats Röschti; or rather, who doesn’t eat Röschti?”

They agreed with my perplexity: after all, despite its conventional association with German-speaking farmers in the Bernese countryside, Röschti is eaten with relish on both sides of the putative divide: by my interlocutors, in fact, among others. And when I asked what form of starch was traditionally served in their part of the country, and was told that mashed potatoes, or purée, was the favored accompaniment to meat dishes in the Romandie, I informed them that my partner, born and raised in the Emmenthal, a solidly Germanophone region of Switzerland, was a lifelong devotee of that particular dish. We were shaking our heads in bemusement at the entrenchment of possibly surpassed cultural divisions in a journalistic shorthand when the house lights dimmed for the second act. (The Italian libretto reminded us that there was also said to be a “polenta divide” separating the German-speaking cantons from Ticino: just another canard?)

*

If the current state of relations between the Francophone and Germanophone regions of Switzerland has improved in recent years, this is surely due in part to the efforts of my friend Sandrine Charlot Zinsli. Sandrine, a Parisian who spent part of her youth in Latin America and studied at Sciences Po, France’s flagship institute for the social sciences, has lived in Zurich for decades with her husband, a Germanophone Swiss architect from the Grisons, and their two daughters. She has worked as a journalist, translator, mediator, and cultural organizer, both as a freelancer and with a variety of associations, including the pan-Swiss Migros supermarket chain, for whose cultural foundation she served as a liaison between the Germanophone and Francophone regions. She was coordinator of the Semaine de la langue française et de la francophonie (SLFF) in Switzerland from 2014 to 2015 and was created a Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres de la République française in 2011.

I met Sandrine in the early 2000s, as the two of us accompanied our very young children to the park near where we both lived with our families on Schindlerstrasse. I recall exchanging recipes and accounts of life as young parents, as well as our experiences as immigrants to Switzerland. Not long afterward, in 2003, I got involved in the Fête de la Musique, the street festival Sandrine initiated, on the French model, in our neighborhood, and which is still happening annually, under a new generation of amateur management. (I have written about the Fête, which has since been renamed the Schindlerplatzfest, here.)

In October of that same year Sandrine founded Aux Arts etc…, a website for the transmission of Francophone culture in the non-French-speaking cantons of Switzerland and an association that mounts cultural events of its own. Together with a small team (Véronique Arlettaz Roncoroni, Marie-Pierre Frossard, Agnès Jullin, and Souad Sellami), Sandrine maintains the site, publishes an editorial (or “édi-tôt”) in an email newsletter, mounts exhibitions, holds public book-club discussions and literary fora, and promotes other cultural organizations, all in the name of disseminating the culture of her homeland and its various colonial outposts. The site features a useful agenda of upcoming local events and posts write-ups of past occasions. (I have myself contributed to these, with brief texts on appearances by Didier Eribon and Edouard Louis, among others.)

The association’s name is a gentle spoof of Serge Gainsbourg’s notorious “aux armes et cætera,” that song itself a reggae-infused vamp of the French national anthem that was the object of considerable vitriol from patriots when it was released in 1979: La Marseillaise, after all, is sacred to a certain strain of French chauvinism, and must be protected from “pollution” by undesirables… For its part, the Swiss website’s call to the arts rather than to arms is an admirably concise expression of Sandrine’s own world view, which combines the progressive politics inherited from her cosmopolitan parents with a ferocious dedication to culture, and a militant (but non-violent) faith in its unifying, socializing, indeed redemptive powers.

Last month, from November 21 to 26, Aux Arts etc… celebrated its 20th anniversary with a week’s worth of events at Theater Stok, a diminutive underground venue near the Kunsthaus Zürich nestled among university buildings and the music conservatory. The offerings were as ambitiously eclectic as the association’s have been for the past two decades, with theatrical and musical performances, readings, podium discussions, literature for children and adults, and a karaoke evening with live instrumental backup and a song-list, prepared in advance with collective input, its numbers mainly from the “metropolitan” French tradition but also featuring titles from the Francophone and Germanophone regions of Switzerland.

Last month, from November 21 to 26, Aux Arts etc… celebrated its 20th anniversary with a week’s worth of events at Theater Stok, a diminutive underground venue near the Kunsthaus Zürich nestled among university buildings and the music conservatory. The offerings were as ambitiously eclectic as the association’s have been for the past two decades, with theatrical and musical performances, readings, podium discussions, literature for children and adults, and a karaoke evening with live instrumental backup and a song-list, prepared in advance with collective input, its numbers mainly from the “metropolitan” French tradition but also featuring titles from the Francophone and Germanophone regions of Switzerland.

The afternoon of the final day of Aux Arts’s residency at Theater Stok, before the evening of live music and partying that would close the week, saw the launch of a book ironically (but accurately) announced as a world premiere. Zwölf Fabeln/Douze Fables de Jean de La Fontaine (Edition Plumes, Fribourg), gorgeously illustrated by Alice Lobsiger, features translations of 12 poems by Jean de la Fontaine, the 17th-century French Aesop, into Bernese German by the father-and-son team of Yves and Philippe Seydoux. On that final Sunday, Yves Seydoux presented a selection of the dialect versions, in each case preceded by a recitation of the original French by Valérie Valkanap, an author and initiator of the book project. The performance was rich and riveting, not only for the artisanship of the (rhyming, word-playing) Bernese translations but also because the two reciters had memorized their selections, and their occasional small lapses and eminently forgivable parapraxes made the whole thing more theatrical, and more human. It was as if we were witnessing the successful meeting of these two very different but related cultures, in the person of two engaging and attractive performers, across their putative divide. I was reminded of the bilingual couple I had met in St-Maurice, she from the canton of Valais, he from Bern, attending an Italian opera; and I thought of my Francophone friend Sandrine, with her Germanophone husband, the excellent Beat Zinsli, incorporating in their marriage, at the basic, personal level, the union of languages that occasionally proves difficult at the Swiss federal level.

The afternoon of the final day of Aux Arts’s residency at Theater Stok, before the evening of live music and partying that would close the week, saw the launch of a book ironically (but accurately) announced as a world premiere. Zwölf Fabeln/Douze Fables de Jean de La Fontaine (Edition Plumes, Fribourg), gorgeously illustrated by Alice Lobsiger, features translations of 12 poems by Jean de la Fontaine, the 17th-century French Aesop, into Bernese German by the father-and-son team of Yves and Philippe Seydoux. On that final Sunday, Yves Seydoux presented a selection of the dialect versions, in each case preceded by a recitation of the original French by Valérie Valkanap, an author and initiator of the book project. The performance was rich and riveting, not only for the artisanship of the (rhyming, word-playing) Bernese translations but also because the two reciters had memorized their selections, and their occasional small lapses and eminently forgivable parapraxes made the whole thing more theatrical, and more human. It was as if we were witnessing the successful meeting of these two very different but related cultures, in the person of two engaging and attractive performers, across their putative divide. I was reminded of the bilingual couple I had met in St-Maurice, she from the canton of Valais, he from Bern, attending an Italian opera; and I thought of my Francophone friend Sandrine, with her Germanophone husband, the excellent Beat Zinsli, incorporating in their marriage, at the basic, personal level, the union of languages that occasionally proves difficult at the Swiss federal level.

Because after all, that is where language most vividly takes place: locally, personally, in live encounters. Reading, singing, and talking—and eating—together. Across the divide.

Aux arts, mes citoyen·nes!

PS: Forthcoming this winter in the Geneva-based periodical Joy-Art is a linked pair of bilingual limericks, written for an issue devoted to “L’érotisme” and taking full advantage of the lurid potential of a Röschtigraben. Repetition and mastery of my childhood trauma?