by Mike O’Brien

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

I take a long time read things. Especially books, which often have far too many pages. I recently finished an anthology of works by Soren Kierkegaard which I had been picking away at for the last two or three years. That’s not so long by my standards. But it had been sitting on various bookshelves of mine since the early 2000s, being purchased for an undergrad Existentialism class, and now I feel the deep relief of finally doing my assigned homework, twenty-odd years late. I think my comprehension of Kierkegaard’s work is better for having waited so long, as I doubt the subtler points of his thought would have had penetrated my younger brain. My older brain is softer, and less hurried.

While I chose this collection as an antidote to topicality and political news, my contemporary anxieties and concerns still found some purchase on these one-and-three-quarter-centuries-old essays of literary indulgence and Christian Existentialism. (Some say Kierkegaard was a proto-Existentialist, or a pseudo-Existentialist, but I don’t think there’s any reason to define such a profligate genre of philosophy so narrowly). As a critic of the press and “the present age”, of course, he has many sharp quips that occasion a smile and a nod, as if to say “you get me, Soren, and I get you”. But that’s the low-hanging fruit, the things that are obvious enough to state unequivocally, like the aphorisms of Nietzsche that sound snappy but do not by themselves reveal anything philosophically significant. The more philosophically meaty works of Kierkegaard’s are more contentious, harder to swallow (especially from a secular standpoint), and sometimes quite baffling on the first encounter (or second, or third).

Of particular interest was “The Sickness Unto Death”, published in 1849, in which he elaborates a spiritual psychology of despair (despair being “The Sickness”, and in the end identified with sin). Being perpetually worried about ecological issues, and about the political and economic conditions mediating humanity’s impact on the planet, despair is always hanging around. It used to be anxiety (another topic of Kierkegaard’s, particularly in 1844’s “The Concept of Anxiety”), when the data on climate change was looking worse and worse. Now that the consensus on global warming is so thick and so dire, the inherent openness of anxiety seems no longer apt to the situation (in Kierkegaard’s conception, anxiety is “the possibility of possibility”, among other formulations). You feel anxious about things that could happen, or things that could go badly. You feel despair about things that will happen, or will go badly. The accumulation of confirming data builds a great wall of probability that seems impenetrable by the merely possible, however desperately you might hold to the abstract truth that the possible still can happen. A despairing state of mind cannot sustain hope for possibility against the weight of probability. This is why Kierkegaard identified God as the only source of a possibility that could provide salvation from despair. I have a hard time seeing the difference between an impossibility which becomes actual through a miracle, and a possibility which is only possible through divine intervention. In either case, the secular situation remains hopeless. Read more »

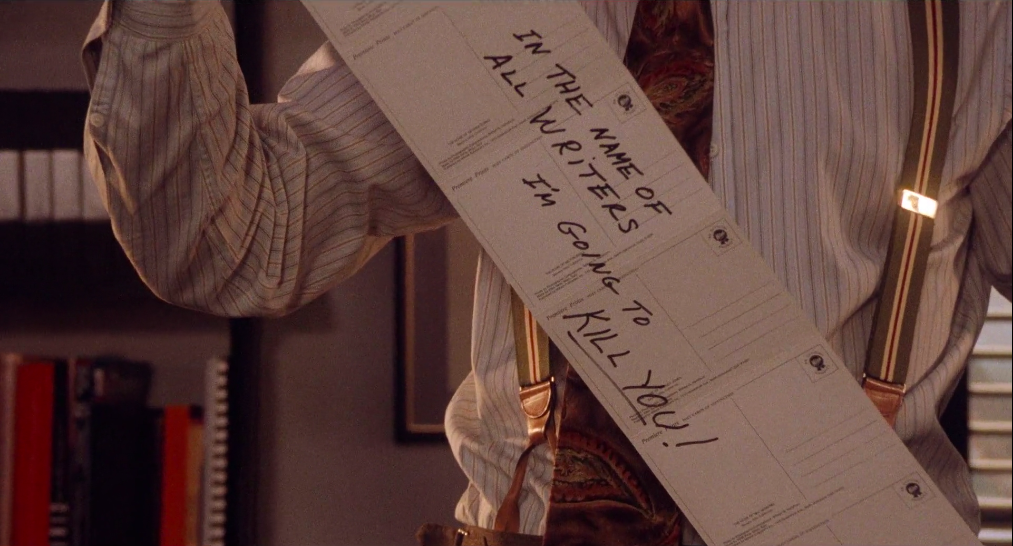

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025.

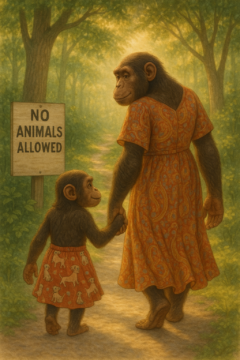

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025. Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.