by David Kordahl

Adam Becker alleges that tech intellectuals overstate their cases while flirting with fascism, but offers no replacement for techno-utopianism.

People, as we all know firsthand, are not perfectly rational. Our beliefs are contradictory and uncertain. One might charitably conclude that we “contain multitudes”—or, less charitably, that we are often just confused.

That said, our contradictory beliefs sometimes follow their own obscure logic. In Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational, Michael Shermer discusses individuals who claim, in surveys, to believe both that Jeffery Epstein was murdered, and that Jeffery Epstein is still alive. Both claims cannot be true, but each may function, for the believer, less as independent assertions, and more as paired reflections of the broader conviction that Jeffery Epstein didn’t kill himself. Shermer has called this attitude “proxy conspiracism.” He writes, “Many specific conspiracy theories may be seen as standing in for what the believer imagines to be a deeper, mythic truth about the world that accords with his or her psychological state and personal experience.”

Adam Becker’s new book, More Everything Forever: AI Overlords, Space Empires, and Silicon Valley’s Crusade to Control the Fate of Humanity, criticizes strange beliefs that have been supported by powerful tech leaders. As a reader of 3 Quarks Daily, there’s a good chance that you have encountered many of these ideas, from effective altruism and longtermism to the “doomer” fears that artificial super-intelligences will wipe out humankind. Becker—a Ph.D. astrophysicist-turned-journalist, whose last book, What Is Real?: The Unfinished Quest for the Meaning of Quantum Physics, mined the quantum revolution as a source of social comedy—spends some of his new book tracing the paths of influence in the Silicon Valley social scene, but much more of it is spent pummeling the confusions of the self-identified rationalists who advocate positions he finds at once appalling and silly.

This makes for a tonally lumpy book, though not a boring one. Yet the question I kept returning to as I read More Everything Forever was whether these confusions are the genuine beliefs of the tech evangelists, or something more like their proxy beliefs. Their proponents claim these ideas should be taken literally, but they often seem like stand-ins for a vaguer hope. As Becker memorably puts it, “The dream is always the same: go to space and live forever.”

As eventually becomes clear, Becker thinks this is a dangerous fantasy. But given that some people—including this reviewer—still vaguely hold onto this dream, we might ponder which parts of it are still useful. Read more »

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing.

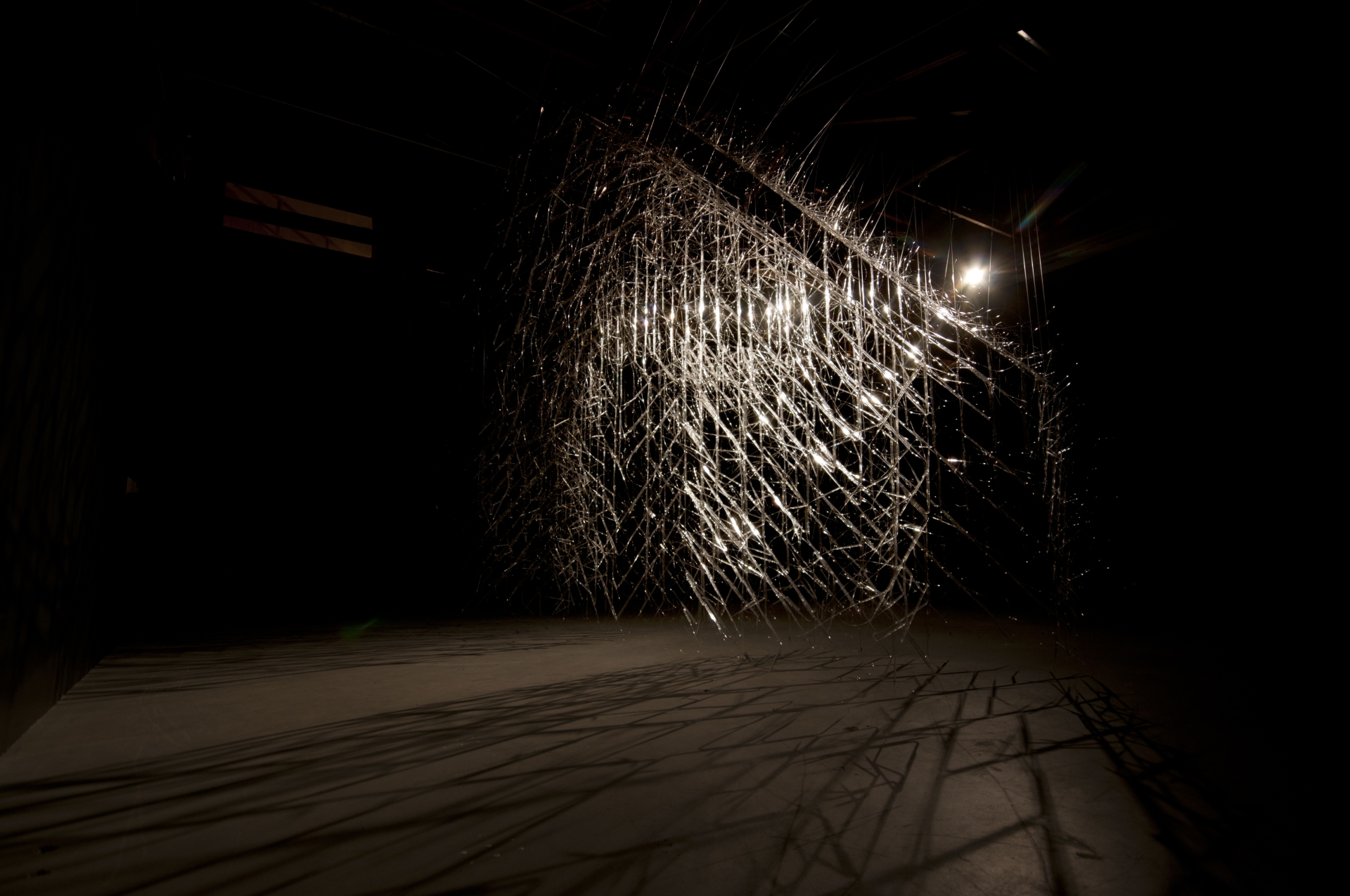

3QD: The old cliché about a guest needing no introduction never seemed more apt. So instead of me introducing you to our readers, maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about yourself, perhaps something not so well known, a little more revealing. Katie Newell. Second Story. 2011, Flint, Michigan.

Katie Newell. Second Story. 2011, Flint, Michigan.

It is a curious legacy of philosophy that the tongue, the organ of speech, has been treated as the dumbest of the senses. Taste, in the classical Western canon, has for centuries carried the stigma of being base, ephemeral, and merely pleasurable. In other words, unserious. Beauty, it was argued, resides in the eternal, the intelligible, the contemplative. Food, which disappears as it delights, seemed to offer nothing of enduring aesthetic value. Yet today, as gastronomy increasingly is being treated as an aesthetic experience, we must re-evaluate those assumptions.

It is a curious legacy of philosophy that the tongue, the organ of speech, has been treated as the dumbest of the senses. Taste, in the classical Western canon, has for centuries carried the stigma of being base, ephemeral, and merely pleasurable. In other words, unserious. Beauty, it was argued, resides in the eternal, the intelligible, the contemplative. Food, which disappears as it delights, seemed to offer nothing of enduring aesthetic value. Yet today, as gastronomy increasingly is being treated as an aesthetic experience, we must re-evaluate those assumptions. In my Philosophy 102 section this semester, midterms were particularly easy to grade because twenty seven of the thirty students handed in slight variants of the same exact answers which were, as I easily verified, descendants of ur-essays generated by ChatGPT. I had gone to great pains in class to distinguish an explication (determining category membership based on a thing’s properties, that is, what it is) from a functional analysis (determining category membership based on a thing’s use, that is, what it does). It was not a distinction their preferred large language model considered and as such when asked to develop an explication of “shoe,” I received the same flawed answer from ninety percent of them. Pointing out this error, half of the faces showed shame and the other half annoyance that I would deprive them of their usual means of “writing” essays.

In my Philosophy 102 section this semester, midterms were particularly easy to grade because twenty seven of the thirty students handed in slight variants of the same exact answers which were, as I easily verified, descendants of ur-essays generated by ChatGPT. I had gone to great pains in class to distinguish an explication (determining category membership based on a thing’s properties, that is, what it is) from a functional analysis (determining category membership based on a thing’s use, that is, what it does). It was not a distinction their preferred large language model considered and as such when asked to develop an explication of “shoe,” I received the same flawed answer from ninety percent of them. Pointing out this error, half of the faces showed shame and the other half annoyance that I would deprive them of their usual means of “writing” essays.

s on a common topic. Yet at noon on May 8th, all 16 high school seniors in my AP Lit class were transfixed by one event: on the other side of the Atlantic, white smoke had come out of a chimney in the Sistine Chapel. “There’s a new pope” was the talk of the day, and phone screens that usually displayed Instagram feeds now showed live video of the Piazza San Pietro in Rome.

s on a common topic. Yet at noon on May 8th, all 16 high school seniors in my AP Lit class were transfixed by one event: on the other side of the Atlantic, white smoke had come out of a chimney in the Sistine Chapel. “There’s a new pope” was the talk of the day, and phone screens that usually displayed Instagram feeds now showed live video of the Piazza San Pietro in Rome.

Danish author Solvej Balle’s novel On the Calculation of Volume, the first book translated from a series of five, could be thought of as time loop realism, if such a thing is imaginable. Tara Selter is trapped, alone, in a looping 18th of November. Each morning simply brings yesterday again. Tara turns to her pen, tracking the loops in a journal. Hinting at how the messiness of life can take form in texts, the passages Tara scribbles in her notebooks remain despite the restarts. She can’t explain why this is, but it allows her to build a diary despite time standing still. The capability of writing to curb the boredom and capture lost moments brings some comfort.

Danish author Solvej Balle’s novel On the Calculation of Volume, the first book translated from a series of five, could be thought of as time loop realism, if such a thing is imaginable. Tara Selter is trapped, alone, in a looping 18th of November. Each morning simply brings yesterday again. Tara turns to her pen, tracking the loops in a journal. Hinting at how the messiness of life can take form in texts, the passages Tara scribbles in her notebooks remain despite the restarts. She can’t explain why this is, but it allows her to build a diary despite time standing still. The capability of writing to curb the boredom and capture lost moments brings some comfort.

Many have talked about Trump’s war on the rule of law. No president in American history, not even Nixon, has engaged in such overt warfare on the rule of law. He attacks judges, issues executive orders that are facially unlawful, coyly defies court orders, humiliates and subjugates big law firms to his will, and weaponizes law enforcement to target those who seek to uphold the law.

Many have talked about Trump’s war on the rule of law. No president in American history, not even Nixon, has engaged in such overt warfare on the rule of law. He attacks judges, issues executive orders that are facially unlawful, coyly defies court orders, humiliates and subjugates big law firms to his will, and weaponizes law enforcement to target those who seek to uphold the law. When this article is published, it will be close to – perhaps on – the 39th anniversary of one of the most audacious moments in television history: Bobby Ewing’s return to Dallas. The character, played by Patrick Duffy, had been a popular foil for his evil brother JR, played by Larry Hagman on the primetime soap, but Duffy’s seven-year contract with the show had expired, and he wanted out. His character had been given a heroic death at the end of the eighth season, and that seemed to be that. But ratings for the ninth season slipped, Duffy wanted back in, and death in television, being merely a displaced name for an episodic predicament, is subject to narrative salves. So, on May 16, 1986, Bobby would return, not as a hidden twin or a stranger of certain odd resemblance, but as Bobby himself; his wife, Pam, awakes in bed, hears a noise in the bathroom and investigates, and upon opening the shower door, reveals Bobby alive and well. She had in fact dreamed the death, and, indeed, the entirety of the ninth season.

When this article is published, it will be close to – perhaps on – the 39th anniversary of one of the most audacious moments in television history: Bobby Ewing’s return to Dallas. The character, played by Patrick Duffy, had been a popular foil for his evil brother JR, played by Larry Hagman on the primetime soap, but Duffy’s seven-year contract with the show had expired, and he wanted out. His character had been given a heroic death at the end of the eighth season, and that seemed to be that. But ratings for the ninth season slipped, Duffy wanted back in, and death in television, being merely a displaced name for an episodic predicament, is subject to narrative salves. So, on May 16, 1986, Bobby would return, not as a hidden twin or a stranger of certain odd resemblance, but as Bobby himself; his wife, Pam, awakes in bed, hears a noise in the bathroom and investigates, and upon opening the shower door, reveals Bobby alive and well. She had in fact dreamed the death, and, indeed, the entirety of the ninth season.

Elif Saydam. Free Market. 2020.

Elif Saydam. Free Market. 2020.