by Katalin Balog

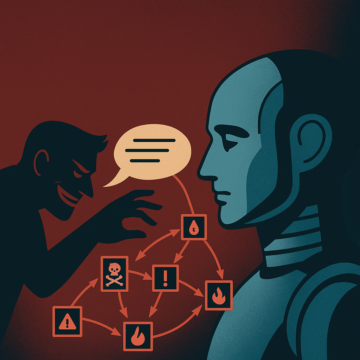

Nathaniel in E. T. A. Hoffmann’s The Sandman loses his sanity over having fallen in love with a wooden doll, the beautiful automaton Olympia. Olympia is an invention of a mad scientist and a master of the dark arts. Like Mary Shelley’s monster, born of the romantic imagination, she is the first literary example of a human-like machine. As one of Nathaniel’s friends observes:

We have come to find this Olympia quite uncanny; we would like to have nothing to do with her; it seems to us that she is only acting like a living creature, and yet there is some reason for that which we cannot fathom.

We can sympathize with the sentiment. But uncanny as the wooden doll might have struck them, contemporary readers of the tale were meant to see Nathaniel’s infatuation as macabre farce – Olympia is clearly robotic and shows no signs of intelligence – orchestrated by dark forces either in the world or in his soul, we can’t know for sure.

The Enlightenment’s fascination with automata (Hoffman’s story was published in 1816) prefigured our predicament, however. We now find ourselves in the curious position of having to give serious thought to the possibility, and increasingly, the reality of relationships with machines that hitherto were reserved for fellow humans. We also seem to have to defend ourselves against – or perhaps reconcile ourselves to – suggestions that AI will soon, perhaps in some regards already, surpass us in some of our most characteristically human activities, like understanding the feelings of others, or creating art, literature, and music. Read more »

In a recent article, ‘

In a recent article, ‘

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so

Even if Ronald Reagan’s actual governance gave you fits, his invocation of that shining city on a hill stood daunting and immutable, so high, so mighty, so permanent. And yet our American decay has been so

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.

Mulyana Effendi. Harmony Bright, in Jumping The Shadow, 2019.