by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by Dwight Furrow

In giving an account of the aesthetic value of wine, the most important factor to keep in mind is that wine is an everyday affair. It is consumed by people in the course of their daily lives, and wine’s peculiar value and allure is that it infuses everyday life with an aura of mystery and consummate beauty. Wine is a “useless” passion that has a mysterious ability to gather people and create community. It serves no other purpose than to command us to slow down, take time, focus on the moment, and recognize that some things in life have intrinsic value. But it does so in situ where we live and play. Wine transforms the commonplace, providing a glimpse of the sacred in the profane. Wine’s appeal must be understood within that frame.

In giving an account of the aesthetic value of wine, the most important factor to keep in mind is that wine is an everyday affair. It is consumed by people in the course of their daily lives, and wine’s peculiar value and allure is that it infuses everyday life with an aura of mystery and consummate beauty. Wine is a “useless” passion that has a mysterious ability to gather people and create community. It serves no other purpose than to command us to slow down, take time, focus on the moment, and recognize that some things in life have intrinsic value. But it does so in situ where we live and play. Wine transforms the commonplace, providing a glimpse of the sacred in the profane. Wine’s appeal must be understood within that frame.

Thus, wine differs from the fine arts at least as traditionally conceived. In Western culture, we have demanded that the fine arts occupying a contemplative space outside the spaces of everyday life—the museum, gallery, or concert hall–in order to properly frame the work. (A rock concert venue isn’t a contemplative space but it is analogous to one—a separate, staged performance designed to properly frame music that aims at impact and fervor rather than contemplation) With the emergence of forms of mechanical reproduction this traditional idea of an autonomous, contemplative space is fast eroding, allowing fine art (and just about everything else as well) to invade everyday life.

But wine, even very fine wine, is seldom encountered in such autonomous, contemplative spaces. It is usually encountered in the course of life, in spaces and times where other activities are ongoing. Formal tastings exist but are the exception. It’s rare to taste wine in a context where casual conversation or food consumption is discouraged as would be the case at a concert hall or museum. Read more »

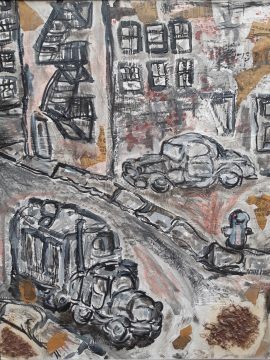

Photo taken while walking with Robin Varghese near Prospect Park in Brooklyn in May of 2015.

by Eric Miller

There is no hope for me but poetry. —Rafaël Newman

1. Toronto in the Seventies was still a filthy city. I was a teen then and because I dropped out of school I got to know the city very well at all hours and in all weathers. I would walk the day into the ground looking at buildings, birds and people. Sometimes I would stop to sketch one of these sights. Charcoal and India ink suited Toronto. Any picture blurred or ran right into its subject matter: grimy, monochromatic. What was my mistake and what was a demonstrable aspect of the scene was materially indistinguishable. When I stood still flakes of ash could be perceived falling at leisure from the sky. Seeping lake freighters corroded lengthwise alongside cracked concrete quays. Guano was caked deep under the Gardiner Expressway as on any Funk Island. I routinely got so tired I couldn’t worry about the future. Every pedestrian knows that the future can be outwalked quite easily on a daily basis. Anxiety does not have much stamina really. I was charitable enough to decant it regular cups of black coffee, but this beverage availed my happiness as much as my misgiving. I worked in the evenings. I was solitary to a degree retrospection finds shocking.

Despite the dirt, it remained a city filled with birds. Chimney swifts twitched, tacked to and fro, chattered, crowded their crescent flocks into the stems of old smoke stacks. Nighthawks stooped on café terraces with grimy, precipitous, monochromatic glamour: Torontonians by plumage, by nature. Their voices were mistakable for traffic sounds. Yet in ancient oaks and beeches, peewees and orioles, and even vireos, sang. Downtown ravines then hosted nesting wood thrushes, as they no longer do. Sometimes my family went netting smelt halfway between the harbour and the beaches. Night herons and bank swallows pursued their respective repertoires (static, antic) where nightfall anglers kindled red and saffron fires in black oil barrels. Gulls bawled like chickens educated in tragic theatre.

Just as I was dropping out of Jarvis Collegiate, I met a nervous person resettled from Vancouver, Rafaël Newman. Read more »

by Jessica Collins

The basic details of the story are known to almost everyone: a Malaysian Airlines flight simply disappeared one night in March 2014 and, more than five years later, the plane has still not been found.

The basic details of the story are known to almost everyone: a Malaysian Airlines flight simply disappeared one night in March 2014 and, more than five years later, the plane has still not been found.

An article by William Langewiesche in the July 2019 edition of The Atlantic revives the theory that the disappearance of Malaysian Airlines flight MH370 was a murder-suicide carried out by the pilot in command: Zaharie Ahmad Shah.

I’m not convinced, but then I’ll admit I’m not sure what to believe. I’m not an aviation expert, but I am a professional epistemologist, and it seems to me that the disappearance of flight MH370 is a fascinating practical case study in the evaluation of publicly available evidence and the assessment of rival theories. Many stories have been told about what happened to MH370, and some of them involve fairly wild conspiracy theories. Here I would simply like to weigh the pros and cons of Langewiesche’s account by comparing it to one of the other plausible competing accounts. It seems to me that there are problems facing both stories.

Let’s start with some more of the known facts.

At 12:42 a.m. on the Saturday morning of March 8 2014, Malaysian Airlines flight MH370, a Boeing 777, took off from Kuala Lumpur International Airport bound for Beijing. At 1:19 a.m., just as the plane was about to enter Vietnamese airspace, the pilot-in-charge, Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah, signed off to Malaysian ground control with the words “Good night, Malaysian three-seven-zero”. That was the final radio transmission received from the aircraft. At 1:21 a.m. the last secondary radar signal was transmitted by the plane’s transponder, at which point the transponder either failed or was switched off. Read more »

by Holly A. Case

On Sunday, May 17, 2015, there was a Lutheran church service in Delmont, South Dakota. Just one. A week earlier—on Mother’s Day—there had been two, one at Hope Lutheran, another at Zion Lutheran. At around 10:45 that morning, during Sunday school at Zion Lutheran, a tornado had ripped through the town, taking out 40 homes and sucking the roof off of Zion Lutheran. A woman later told us there was a pipe organ “trapped” inside, as if it was a living victim of the storm.

On Sunday, May 17, 2015, there was a Lutheran church service in Delmont, South Dakota. Just one. A week earlier—on Mother’s Day—there had been two, one at Hope Lutheran, another at Zion Lutheran. At around 10:45 that morning, during Sunday school at Zion Lutheran, a tornado had ripped through the town, taking out 40 homes and sucking the roof off of Zion Lutheran. A woman later told us there was a pipe organ “trapped” inside, as if it was a living victim of the storm.

Nine people were injured; no one was killed. “We have four solid blocks of nothing,” said Delmont’s mayor in an interview with a journalist a few days later.

Delmont was a town of roughly two hundred inhabitants pre-tornado. It has fewer than half that now. Sixty maybe. A week after the tornado, I and some of my family went to the Sunday service at Hope Lutheran. We figured most of the town would be gathered there since pretty much all of Delmont was Lutheran. We also presumed the differences between Lutherans to be insignificant. Read more »

Sughra Raza. “Steep-le-chase!”; June, 2019, Rwanda.

Sughra Raza. “Steep-le-chase!”; June, 2019, Rwanda.

Digital photograph.

by Dave Maier

The relation between mind and matter is a perennial philosophical conundrum for a reason. If the workings of the mind depend too much on the physical material that seems to house it, then it can be hard to see how there’s conceptual room for human agency. On the other hand, if they don’t depend on it at all, then it’s hard to understand why such things as brain injury or the ingestion of this or that chemical substance should have any effects at all, let alone the reliably predictable effects that often result. Something’s gotta give!

The relation between mind and matter is a perennial philosophical conundrum for a reason. If the workings of the mind depend too much on the physical material that seems to house it, then it can be hard to see how there’s conceptual room for human agency. On the other hand, if they don’t depend on it at all, then it’s hard to understand why such things as brain injury or the ingestion of this or that chemical substance should have any effects at all, let alone the reliably predictable effects that often result. Something’s gotta give!

We’re certainly not giving up the truths of natural science. However, just as allowing agency to slip the bonds of nature makes a lot of things inexplicable, so does getting rid of it entirely. (Imagine trying to explain, say, the Civil War without even once appealing, even implicitly, to the notion that human beings act on their beliefs and desires, and are thereby subject to praise and blame from others.) The two types of explanation need to learn to live together, as equally valuable tools in our conceptual toolbox. We need to get clearer, then, on how exactly our normative explanations, and our practices of praise and blame, actually play out. What are they good for, and what are their proper domains of application? What happens when we press them too hard, or try to use them for something they’re not designed to do? How can we get them to play nicely with their conceptual colleagues?

Problems result not only when we use normative language like we do the laws and concepts of science (a common error), but also when normative concepts or principles get in each others’ way, which they will even when we’re being careful, because that’s the nature of the beast. (And of course we’re not always careful.)

Let’s start with a look at a widely used principle, applicable not simply in moral contexts but to normativity generally: that “ought implies can.” The point of this principle is fairly intuitive. [Note: as a speaker of American English, I will be using “ought” and “should” interchangeably here (my apologies to the Queen).] It is at least very often true that it makes no sense to criticize someone for failing to do something which is impossible. On the other hand, there are many different potentially relevant senses and degrees of (im)possibility. Read more »

by Michael Liss

It is a big cross. A really big cross. Forty feet in height, made of granite and concrete, The Bladensburg Peace Cross stands tall and straight for all to see.

It is a big cross. A really big cross. Forty feet in height, made of granite and concrete, The Bladensburg Peace Cross stands tall and straight for all to see.

The Peace Cross, sponsored by the American Legion, was built in 1925 in the aftermath of World War I to memorialize the sacrifice of 49 Prince George’s County servicemen. It was paid for by the Legion, and by subscription of local residents and businesses. In 1961, maintenance of it was passed to the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, and the land it currently stands on is State land, in a traffic median, the cost of maintenance paid for by the taxpayers of Maryland.

If you are just a little bit attuned to the First Amendment (religion portion), you might be interested in how that last part meshes with “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

It is a perceptive question, one that the Supreme Court grappled with and decided this last Thursday in American Legion v. American Humanist Association. The Peace Cross, they ruled in a 7-2 decision, may continue to stand on public land and be paid for with public funds.

This is the kind of wonky, incredibly subjective ruling that makes my heart go pitter-patter. I’m not sure I agree (or disagree) with the result, but I love the tortured efforts of most of the Justices to do the best they could under difficult circumstances. This is not an easy one. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Robert Fay

I’m not typically a reader of White House memoirs, but after finishing the new biography of diplomat Richard Holbrooke, Our Man (2019) by George Packer, I became intrigued by depictions of Obama’s management style in dealing with Holbrooke, Hilary Clinton and others. I soon picked up The World As It Is (2018) by former Obama advisor Ben Rhodes, which has been described as the best “inside” look of Obama to date. Rhodes tells us enough Obama anecdotes to bring the man into focus. And while none of it is terribly surprising, I was intrigued to learn that Obama, despite being President, continued to see himself as an outsider, as someone who, by virtue of his own personal journey and outlook, could never truly become enculturated to power and authority, despite being the executor of state power for eight years.

It seemed Obama’s self-view as an outsider had less to do with being African-American or as someone who had lived in Indonesia as a child, but more to do with being, at heart, a writer (it’s no coincidence that Rhodes, one of his closest advisors, was a speechwriter who had an MFA in creative writing from NYU). Obama’s memoir Dreams from My Father (1995) garnered the kind of literary praise that few politicians since Winston Churchill have received. During his presidency, Obama carved out four or five hours of “alone-time” in the White House Treaty room each night to read books, review documents and often just to think. Obama’s famous coolness, his so-called detachment, was likely a misreading of his observational mode with people, a common trait among writers who find you can learn more from a “scene” by observing people than by inserting yourself into the action.

But most of all, I was struck by a random comment Obama made to Rhodes regarding criticism from American Jews over his Israel policy. “I came out of the Jewish community in Chicago,” he said. “I’m basically a liberal Jew.” Read more »

by Sarah Firisen

Many years ago, my father and I were at a backyard BBQ in New Jersey hosted by someone we barely knew, I think they were somehow connected to my step-mother. At some point, the topic of flag burning came up and, before we knew it, we were engaged in an extremely heated debate on what patriotism actually means (I believe that the rights the flag stands for include the right to burn it). The debate ended up with a large group of people holding beers and hot dogs decrying the liberal anti-Americanism of the two of us. Not the best way to spend a summer afternoon. These days, it’s possible, in fact too easy, to repeat the unpleasantness of that afternoon all the time on social media. I try my best to steer away from the soul sucking void that is having debates on Facebook with friends of friends. We all have those people in our lives with whom we have a moral or political disconnect and that those people will sometimes make comments that will inflame our more simpatico friends may be inevitable, but doesn’t have to be engaged with and perpetuated. Such debates don’t change hearts and minds. Full disclosure, I admit, sometimes I don’t follow my own advice here as well as I should, but I try.

Many years ago, my father and I were at a backyard BBQ in New Jersey hosted by someone we barely knew, I think they were somehow connected to my step-mother. At some point, the topic of flag burning came up and, before we knew it, we were engaged in an extremely heated debate on what patriotism actually means (I believe that the rights the flag stands for include the right to burn it). The debate ended up with a large group of people holding beers and hot dogs decrying the liberal anti-Americanism of the two of us. Not the best way to spend a summer afternoon. These days, it’s possible, in fact too easy, to repeat the unpleasantness of that afternoon all the time on social media. I try my best to steer away from the soul sucking void that is having debates on Facebook with friends of friends. We all have those people in our lives with whom we have a moral or political disconnect and that those people will sometimes make comments that will inflame our more simpatico friends may be inevitable, but doesn’t have to be engaged with and perpetuated. Such debates don’t change hearts and minds. Full disclosure, I admit, sometimes I don’t follow my own advice here as well as I should, but I try.

Perhaps even more pointless is having fights with utter strangers who just happen to subscribe to the same Facebook groups you do. The other day I felt unusually compelled to comment on a New York Times Modern Love posting on Facebook. The story was about a woman who listened to a tarot card reader and took her “predictions” very seriously. Now as far as I’m concerned, if you make the choice to write about your private life in a public sphere, you’re fair game for other people to comment on your choices – indeed, I open myself up for this in writing for this blog, and I get that. I’m not sure why I bothered to comment, why do people write letters to newspapers? But I certainly believe I had a right to state my opinion. A fellow reader disagreed and started a personal attack on me and my judgement of the story writer. I should have left it at that, I didn’t, I answered back. Read more »

Cars seen through a rusty metal fence in Brixen, South Tyrol, in May, 2016.

How, then, do we get from H. Rider Haggard to Anthony Bourdain? Let’s start with the easy and straightforward. Both are white men, as are Joseph Conrad and Francis Ford Coppola for that matter. Haggard was British; he was born in the 19th century and died in the 20th (1856-1925). Bourdain was American, born in the 20th and died in the 21st, at his own hand (1956-2018). It’s easy enough to interpolate the other two: Joseph Conrad, Polish-British (1857-1924); Francis Ford Coppola, American (1939 and still living).

So much for bare biography. It’s the imaginative life that interests.

Haggard wrote a ton of novels, many of them well-known. The Allan Quatermain stories, starting with King Solomon’s Mines, are said to have inspired the character Indiana Jones. She: A History of Adventure marked the beginning of a different series and is one of Haggard’s best-known novels. If not exactly a high-culture masterpiece, it has been quite influential as one of the founding texts of “lost world” fiction. Wikipedia tells us that it’s been made into 11 films and sold over 83 million copies, making it an all-time fiction best seller, and has been translated into 44 languages.

by Bill Murray

A few months ago, Mikhail Saakashvili, ousted leader of the former Soviet Republic of Georgia and the Ukrainian town of Odessa, predicted that Russia would next attack either Sweden or Finland. A few days ago I visited the Finnish and Russian border towns of Lappeenranta and Выборг (Vyborg), and if war preparations in these two places are any indication, Sweden had better man the barricades.

For people of a certain age, coming to Russia from any direction sends up a certain Cold War frisson. Today we shall cross the border from Finland, which has been fought over and traded between Sweden and Russia for centuries.

As early as 1293 a Swedish marshal built a castle in Vyborg, now Russian. The castle traded hands repeatedly between the Swedes and the then Republic of Novgorod. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and loss of fortresses in Narva, Tallinn and Riga, Vyborg Castle is the only European-style medieval castle in Russia. Its current iteration is touted as a prime tourist destination but appears to be randomly, and arbitrarily, closed for renovation.

As early as 1293 a Swedish marshal built a castle in Vyborg, now Russian. The castle traded hands repeatedly between the Swedes and the then Republic of Novgorod. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and loss of fortresses in Narva, Tallinn and Riga, Vyborg Castle is the only European-style medieval castle in Russia. Its current iteration is touted as a prime tourist destination but appears to be randomly, and arbitrarily, closed for renovation.

Viipuri, in the Finnish appellation, was capital of Finnish Karelia and a vital outlet to the sea until Vyborg was seized by the Red Army in June of 1944. John H. Vartenen, in a 1979 New York Times article:

The Finns felt that to some extent they had won the war on the ground by forcing the Russians to come to the negotiating table. On the other hand, they felt that they lost at the table because, though the Russians had never moved more than 50 miles into Finland, the Finns lost eastern Karelia, including the area’s second‐largest city, Viipuri.

While Vyborg is almost exactly the same size today as when it was taken from the Finns, for 75 years it has been Russified. If you were twelve years old on the day Viipuri fell and had a child of your own five years later, that child would now be 70. Teaching Finnish was out of the question in early Russian-occupied Vyborg, but even for those who quietly did so, use of the language is dying – except in tourism. Read more »

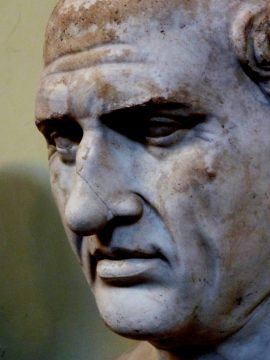

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Cicero’s philosophical dialogues are notoriously difficult. In some cases, as with the Academica and the Republic, their fragmentary state exacerbates the challenge of interpretation. In other cases, as with On Ends, the breadth of the discussion makes it difficult to locate the thread. In every case, Cicero stays true to his Academic skeptical training of opposing every argument with another argument. In some instances, one line of reasoning comes out clearly best, but in others, it is not so clear. And then there is On the Nature of the Gods. It is a special case. Let us explain.

The overall structure of On the Nature of the Gods is quite simple. The theologies of three philosophical schools are represented, each with a Roman mouthpiece. Epicureanism is represented by Velleius, Stoicism by Balbus, and Academic skepticism by Cotta. Cicero writes himself into the dialogue, too, as listening in and promising not to tilt the verdict in favor of his fellow Academic, Cotta. Velleius proceeds to give an outline of Epicurean theology, complete with an account of how it is possible to know things about the gods, what the gods are like, and how we should live in light of these truths. In short, Epicureans believe that we know about the gods because we have deeply held conceptions of them, which must have antecedent causes. The gods have human bodies and they live lives free of care for eternity. Consequently, we should not fear the gods, because they take no notice of us. Cotta the Academic skeptic then proceeds to demolish the Epicurean case. Why trust preconceptions when they are so often wrong? If the gods have human-like bodies, how can they be immortal? And if the gods don’t care about us, then what’s the point of religion or piety at all? Isn’t Epicureanism really just atheism? Read more »

by Jonathan Kujawa

I just returned from the joint Vietnam-US math conference held at the International Center for Interdisciplinary Science and Education in beautiful Quy Nhon, Vietnam.

While it is a human endeavor, mathematics doesn’t care about gender, race, wealth, or nationality. One of the great pleasures of the math community is finding yourself on common ground with people from around the world. It is for good reason movie aliens usually first communicate using prime numbers and we chose to include math on the Voyager spacecraft’s Golden Record [1].

In this spirit, the American Mathematical Society and the Vietnamese Mathematical Society organized a joint meeting to encourage connections, collaborations, and friendship between the two countries’ mathematical communities. Given the fraught history between the two countries, the importance and symbolism of the conference were especially notable. During the cold war, even innocuous communication between mathematicians on the two sides was quite difficult. Even sending a letter, nevermind a conference to meet in person, was a rare event. More than a few results were discovered independently on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Progress was often held up due to not knowing of the latest advances on the other side. The Soviet Union, for example, made it difficult for its citizens to participate in the International Congress of Mathematicians. In an age where internationalism and science are treated with skepticism, building direct connections between countries’ citizens is a wonderful thing. The conference even made the local evening news!

Another great thing about these sorts of conferences is the breadth of mathematics covered. This meeting covered everything from topology to mathematical physics, from modeling natural gas flows in pipelines to groups and representations (my own area of research). As part of this, the meeting had six plenary talks by eminent mathematicians covering the various fields represented at the conference.

One of the speakers was Henry Cohn, arguably the world expert on sphere packings. Dr. Cohn gave a fantastic talk about the latest breakthroughs in this area. Nearly three years ago here at 3QD we talked about an amazing breakthrough in sphere packing. This included work by Dr. Cohn. As we’ll see, Dr. Cohn and his collaborators haven’t been napping. Read more »

by Anitra Pavlico

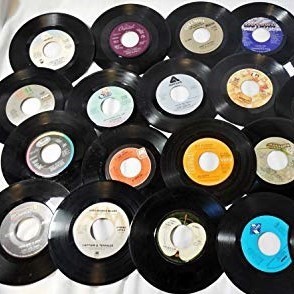

What has happened to music? To the joy of cozying up with your records, tapes, or CDs and your music source, whether it was a boom box, or stereo with faux-wood speakers taller than a small child, or Walkman? It used to be simple to figure out where to buy music and how to listen to it. You went to the local record store, and then you brought it home and absconded to your bedroom, where you cranked your new purchase as loud as you could before your parents knocked on the door and told you to turn it down. There was a spatial aspect to music, as the music store was obviously circumscribed in space, with different sections for different tastes. Listening also usually took place in an intimate setting, layered like a palimpsest with memories of years past. Well before five-disc (and then 100-plus-disc) CD changers, we listened to one album at a time, and usually with the songs in the same order that the artist or the producer intended. It was a form of communion, however illusory, with the musician. There were also visual and tactile elements, as you had something to hold in your hands and pore over–liner notes, album credits, lyrics, glossy pictures of the band members. Did anyone ever vote to relinquish these sensory companions to the music-listening experience?

I did not have access to the ultimate in high fidelity as a kid, and I remember practically gluing my ear to my Sony Dream Machine clock radio’s speaker. When my parents bought me my first “boom box” they managed to find one with only one speaker. It hardly boomed, but it was still more than sufficient. In my mind’s ear, even these devices had much better sound quality than the digital music we have come to rely on. At the source, at least, the sound was fuller, less broken down or compressed into heartless bits and bytes. We did also have a lot of vinyl, not because we were hipsters, but because it was the 1970s.

I can’t pretend that it always makes a difference, today’s lesser sound quality. It was a trade-off that didn’t trouble me for years as I joined the rest of the world in celebrating the fact that virtually my entire music collection could fit on an iPod that I could carry around with me. As years go by, and you simply lose the memory of what music used to sound like, you don’t realize that convenience has supplanted most of the other elements of the experience of listening to music. Read more »

by Brooks Riley