by Tim Sommers

“The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point.” –Gabriel Garcia Marquez in One Hundred Years of Solitude

Here’s an apocryphal story that is so good, it should be true. In 1770 Captain Cook became the first European to land in Australia and so the first to encounter a leaping animal with a baby in its pouch. He pointed at it and asked a nearby aboriginal, “What is that?”

“Kan-ga-roo,” our fictional indigenous person responded. And, so, we call them “kangaroos”. Which means, in that local language, “I don’t know what you are saying.”

I always associate that story with Willard Van Orman Quine’s essay, “Ontological Relativity”, because the centerpiece of the essay is what he calls a “radical translation” scenario. We are trying to learn to translate a language that we have no independent knowledge of, a language that, as far as we know, is not related to any other language that we already know how to translate. Suppose a rabbit goes hopping by and a native speaker points at it saying, “Gavagi!” Even assuming we all agree on what pointing is, and we all think that pointing and talking at the same time associates the pointing with the talking, and we are sure that the spatio-temporal area occupied by what we would call a rabbit is what is being pointed at, assuming all that, how do we know whether they mean “There goes a rabbit!” or “Look at those undetached-rabbit-parts!” or “Some rabbitizing is going on over there”. Or, if you do the pointing, how do you know that what they are saying to you is not just, “I don’t know what you are saying”.

I know, I know, only a philosopher would wonder that. But, consider: what we think exists should be revealed by what we say, but what if it’s not? What if what exists is relative to what we say, but we can never be absolutely sure what anyone is saying about what there is? What if ontology, the part of metaphysics that is supposed to be, at a minimum, a catalogue of things that we think exist and are real, is relative to language and language is always indeterminate with respect to ontology. Should we be worried about this? Read more »

Madeleine LaRue: It did turn out to be pretty mammoth! How about I tell you, by way of introduction, about the first time I met Bichsel in person. He’d come to read at the Literarisches Colloquium in Berlin, the center of the grand old West Berlin literary establishment. It was November, it was dark and cold, and when he emerged at the back of the room and started walking up toward the stage, wearing the same black leather vest he’s been wearing for the past forty years, I think we were all a little worried about him. He was eighty-two then, and he looked exhausted. It had been a while since he’d been on such an extensive reading tour outside of Switzerland. He got to the stage and settled into his chair. The moderator welcomed him and asked how it felt to be back in Berlin—a simple question, a nice, easy opener. Bichsel still seemed tired, but as he leaned back and said, very slowly, in his lilting Swiss accent, “Ja, ja, Berlin,” his eyes lit up and he launched into a story about his first time in the city, in the early 1960s, and how he got caught in the middle of a bar fight with some people! Who turned out to be Swiss! And they all got thrown out onto the street together, and he’ll never forget it! And ja, ja, Berlin—and from his very first word, we all became like delighted children at Grandfather’s feet, totally enraptured, utterly unwilling to go to bed until we’d heard just one more story, pleeeease? And he himself became younger, full of life, charming and hilarious and genuine and profound.

Madeleine LaRue: It did turn out to be pretty mammoth! How about I tell you, by way of introduction, about the first time I met Bichsel in person. He’d come to read at the Literarisches Colloquium in Berlin, the center of the grand old West Berlin literary establishment. It was November, it was dark and cold, and when he emerged at the back of the room and started walking up toward the stage, wearing the same black leather vest he’s been wearing for the past forty years, I think we were all a little worried about him. He was eighty-two then, and he looked exhausted. It had been a while since he’d been on such an extensive reading tour outside of Switzerland. He got to the stage and settled into his chair. The moderator welcomed him and asked how it felt to be back in Berlin—a simple question, a nice, easy opener. Bichsel still seemed tired, but as he leaned back and said, very slowly, in his lilting Swiss accent, “Ja, ja, Berlin,” his eyes lit up and he launched into a story about his first time in the city, in the early 1960s, and how he got caught in the middle of a bar fight with some people! Who turned out to be Swiss! And they all got thrown out onto the street together, and he’ll never forget it! And ja, ja, Berlin—and from his very first word, we all became like delighted children at Grandfather’s feet, totally enraptured, utterly unwilling to go to bed until we’d heard just one more story, pleeeease? And he himself became younger, full of life, charming and hilarious and genuine and profound.  Having before you an iced mango

Having before you an iced mango

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

On a whim I decided to visit the gently sloping hill where the universe announced itself in 1964, not with a bang but with ambient, annoying noise. It’s the static you saw when you turned on your TV, or at least used to back when analog TVs were a thing. But today there was no noise except for the occasional chirping of birds, the lone car driving off in the distance and a gentle breeze flowing through the trees. A recent trace of rain had brought verdant green colors to the grass. A deer darted into the undergrowth in the distance.

On a whim I decided to visit the gently sloping hill where the universe announced itself in 1964, not with a bang but with ambient, annoying noise. It’s the static you saw when you turned on your TV, or at least used to back when analog TVs were a thing. But today there was no noise except for the occasional chirping of birds, the lone car driving off in the distance and a gentle breeze flowing through the trees. A recent trace of rain had brought verdant green colors to the grass. A deer darted into the undergrowth in the distance.

Sughra Raza. Enlightened, April, 2019.

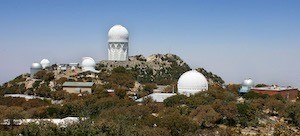

Sughra Raza. Enlightened, April, 2019. When I returned to school after my first marriage ended, I had to decide what to study. I’d been working toward a degree in history when I dropped out of a community college to get married, but I’d always been drawn to astronomy. One of the reasons I chose astronomy over history, or any other option, was that I felt that astronomy contained many of the other things I was interested in. To put it another way, I thought that if I didn’t study astronomy, I would regret it, but if I did study it, I wouldn’t necessarily lose touch with the other things I was interested in because they were all part of astronomy, in one way or another.

When I returned to school after my first marriage ended, I had to decide what to study. I’d been working toward a degree in history when I dropped out of a community college to get married, but I’d always been drawn to astronomy. One of the reasons I chose astronomy over history, or any other option, was that I felt that astronomy contained many of the other things I was interested in. To put it another way, I thought that if I didn’t study astronomy, I would regret it, but if I did study it, I wouldn’t necessarily lose touch with the other things I was interested in because they were all part of astronomy, in one way or another.