by Akim Reinhardt

Several co-workers, all of whom have Ph.D.s. An old friend who’s a physicist. Scads of family members of both blue and white collar variety. Numerous neighbors. And of course the well dressed, kindly old women who occasionally show up at my door uninvited, pamphlets in hand.

Several co-workers, all of whom have Ph.D.s. An old friend who’s a physicist. Scads of family members of both blue and white collar variety. Numerous neighbors. And of course the well dressed, kindly old women who occasionally show up at my door uninvited, pamphlets in hand.

One can point to general trends about the powerless, the vulnerable, and the less-educated as likelier to believe in God than those full of book learnin’ or living the good life. But But when the vast, vast majority believe, the believers represent a thorough cross-section of society. And so my daily existence, and that of many if not most atheists, involves sharing interactions and ideas with all sorts of people, wealthy and poor, old and young, male and female, well educated and not, who embrace magical thinking to one degree or another. Who believe either quite vividly or a bit vaguely in a supreme, celestial being or force with at least some degree of sentience and even an agenda. A god who sees and hears us. And perhaps a soul or spirit within in us that lives on after our bodies have given out, some ethereal expression of immortality, some mechanism of continuity after this go-around is done, some medium of transcendence into a heavenly (or hellish) destiny, or perhaps into another corpus, whether animal or human yet unborn, and from there a fresh start.

We, the atheists, the ones who, if you are anything like me, cannot believe even if we desperately want to because we find it patently unbelievable, are a small minority around the world. Here in the Untied States we number a scant 3%. All around us, a great majority run the gamut: agnostics (only 4%) who may one day end up like us; a growing number of people who just don’t think about it all that much until they end up in some proverbial foxhole; conscious believers, such as my friend the physicist, who might be like us in countless other ways; hardier believers hungrily gulping up the magic; and ever up the scale eventually peaking with a small number of badly broken and certifiably insane people who think they themselves are this or that saint or such and such deity. Read more »

Johnny spoke softly in a voice just past the threshold of manhood. His smile, mistaken for charm, was longing. I could see the pentimento of the child still in him.

Johnny spoke softly in a voice just past the threshold of manhood. His smile, mistaken for charm, was longing. I could see the pentimento of the child still in him.

It does not take long for history to repeat itself. It was only a little over a decade ago that overzealous lending, lax underwriting standards, unrealistic collateral valuations, borrowers not understanding loan terms, an exploding derivative securities market–and a dozen or so other factors–led to a massive crash in the housing market. Today in the United States we have outstanding student loan debt of $1.5

It does not take long for history to repeat itself. It was only a little over a decade ago that overzealous lending, lax underwriting standards, unrealistic collateral valuations, borrowers not understanding loan terms, an exploding derivative securities market–and a dozen or so other factors–led to a massive crash in the housing market. Today in the United States we have outstanding student loan debt of $1.5

While Trump’s immigration politics makes international headlines almost every day, the disaster of the European immigration policies rarely becomes international news. A recent exception is the case of Captain Carola Rackete, and it is a telling one. With all the potential for a good story, Rackete’s journey is both standing for and at the same time distracting from the actual complex mess of European immigration politics.

While Trump’s immigration politics makes international headlines almost every day, the disaster of the European immigration policies rarely becomes international news. A recent exception is the case of Captain Carola Rackete, and it is a telling one. With all the potential for a good story, Rackete’s journey is both standing for and at the same time distracting from the actual complex mess of European immigration politics. When the flight delay is announced, we ask what it is we have done wrong. From airlines and the world at large, the answer is rarely forthcoming, so we must look inward instead.

When the flight delay is announced, we ask what it is we have done wrong. From airlines and the world at large, the answer is rarely forthcoming, so we must look inward instead.

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

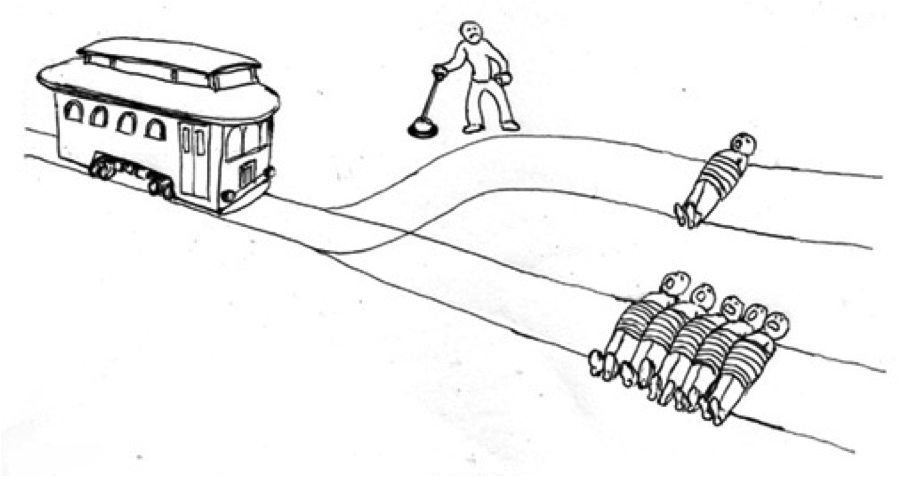

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”