by Katie Poore

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.

Waiting on the platform, I happened upon an article in The Atlantic. The author’s name was Jedediah Britton-Purdy. I clicked the Instagram link with immediate fascination, not because of the notability of that name—it strikes me as so quintessentially American—but because I spent days and weeks with his book After Nature last year, slogging through an undergraduate thesis centered on the intersection of the environment and literature.

Purdy’s article is called “The Concession to Climate Change I Will Not Make.” In it, he explains his rationale for maintaining hope in a world that seems to be, quite literally, burning down around us. To him, this hope means, at least in part, continuing to have children.

This struck a chord with me, perhaps because it was eerily similar to a conversation I had with my mother over the holidays, where I professed a sense of hopelessness about the world and its seemingly impending expiration date. Sometimes it made me terrified to have children, I told her. Thinking about what they might inherit felt almost cruel. Read more »

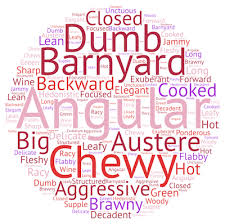

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

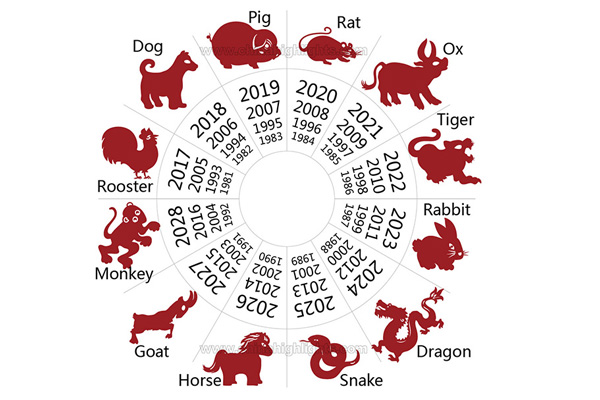

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it.

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it. Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.

Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.

1.

1. I have an awful confession to make. I haven’t made up my mind about whether President Trump should be convicted and removed from office.

I have an awful confession to make. I haven’t made up my mind about whether President Trump should be convicted and removed from office. When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.

When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.

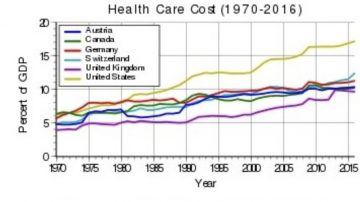

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.