by R. Passov

The economics of health insurance is of particular importance today. Health insurance has become a major issue of public policy. Some form of national health insurance is very likely to be enacted within the next few years. —Martin Feldstein 1

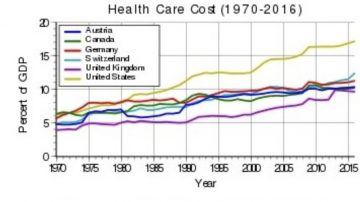

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

Turns out, like many economists, he was half right. While a truly national health scheme is still in the making, health care spending is now 18% of GDP, and growing.

Feldstein, known to his friends as Marty, was an interesting guy. For outstanding contributions to economics by an economist under 40, he was awarded the Bates Medal. He was President Reagan’s chief economic advisor, a long-time teacher at his alma matter, Harvard, and managed to retain the presidency and CEO titles at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) from 1977 until his passing in 2019. (He stepped aside from 1982 to 1984 to serve Reagan.)

The NBER describes itself as a private, non-profit research organization and then adds that it has been the source for most leaders of the Council of Economic Advisors. The Council is in fact a government entity, constituting the chief economic advisors to the Office of the President, while the National Bureau, which sounds like it is, is not.

Anyway, fifty years ago, Feldstein took his economics – the ‘markets solve everything’ kind – and reached the following conclusion: The problem with healthcare is Health Insurance. Eliminate insurance wrote Feldstein, and market forces would reign in the runaway price of health services.

You get to this conclusion by over-rotating on Moral Hazard, the notion that if you happen to have insurance you’re more likely to consume care; more likely to visit doctors and endure pricy treatments that you may or may not need.

And something else: If you have health insurance you’re more likely to continue to engage in behaviors that lead to bad outcomes. Why? Because whatever those bad outcomes may be, your losses are fixed. You’re insured.

This, in part, led Feldstein to argue that eliminating insurance would force accountability both in terms of how much healthcare is consumed as well as in the prices for medical intervention. An interesting argument that more or less stuck around for a long time.

Gary Becker of the University of Chicago, the epicenter of ‘free market economics’, thinks along the same lines as Feldstein. Healthcare is enough of a market good that it can be ‘priced’; folks are somehow capable of exchanging just the right amount of their wealth for just the right amount of additional health. (Of course, I’m simplistically paraphrasing a complicated assertion.) 2

Becker says something else: More healthcare begets a greater demand for healthcare. More healthcare means people live longer. The longer we live the more of us there are. The more of us there are the greater is the demand for healthcare. This seems reasonable.

Here’s something else that Becker stretches out of some simple math (and which I’m stretching further in this piece.) As incomes grow and healthcare spreads, populations increase in average age. This combination of growing incomes and aging results in successive healthcare innovations that are not that effective when viewed from the perspective of the individual.

At the turn of the 20th century life expectancy in the U.S. was just a little over 40 years for the average male. So, supposing the science were there, investing in a very expensive cure for a chronic illness that afflicts folks in their sixties was a non-starter. On the other hand, investing in vaccines made a lot of sense. It helped young folks survive. As life expectancy grew, the market for drugs that are more expensive to develop also grew. But something else happened as well.

A vaccine that works is highly effective. But as populations both grew in size and in average age, the relative effectiveness of medicines declined. This is an ‘on average’ statement. Yes, antibiotics clear up bacterial pneumonia which, if you need this treatment, is very important!

But Lipitor, until just recently the largest selling drug ($13 billion per year in sales at its peak) while likely significantly lowering the odds of a heart attack in a properly treated cohort (careful here as I’m not a doctor), is at the same time, not all that impactful for any single individual.

Another way of getting to Becker’s conclusion is this: if a set of drugs is making folks live longer then the next drug introduced into the set, since it’s enjoying the benefits from the effect of prior drugs, does not need to be that effective on its own. Making a small difference in the lives of lots of folks is a good business.

Becker also felt a need to speculate as to why folks seek health insurance while continuing to engage in risky activity. Perhaps this behavior is not so irrational after all.

Becker’s argument goes like this: The obese smoker gets ‘utility’ (enjoyment) from over-eating and then having a cigarette. And though this behavior likely has a negative impact on life expectancy, perhaps the individual is rationally estimating the chances of new technology reducing the risks associated with her risky behavior. If this were the case, then the individual is ‘rationally’ balancing the utility from engaging in risky behavior against the likelihood that new cures will take away the risk.

While Becker’s speculation may or may not have merit, technology and healthcare do seem stuck in a costly embrace. In 1991, Burton A. Weisbrod made clear the reasons why: Healthcare suffers from a wide-open door to technology. 3

Healthcare technology expands the scope of what’s treatable. This results in a stream of new technology to address an ever-increasing field of treatable conditions.

This feed-back loop, says Weisbrod, is at the heart of the runaway costs that we are seeing in the US. And, he points out, our health insurance is not effective at screening new technologies. It’s hard for doctors to say no. If they do, they’re exposed to second guessing (to lawsuits.) And, measures of effectiveness for new technologies are in many cases questionable or not in effect.

Can this open door to technology be slowed or somehow managed? How about the even harder question: Is this open door beneficial?

The UK has its National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, commonly referred to as NICE (a euphemism direct from Monty Python.) They develop assumptions about the relative value of new treatments. If these assumptions are not high enough then new treatments are not approved for reimbursement under the national healthcare system and as a result well-to-do folk fly off to India where medical tourism flourishes.

Introducing a medical review board into the politics of US healthcare is a no-go. Perhaps this is what scares so many about Elizabeth Warren’s healthcare plan(s). After all, Medicare for All implies that somewhere, a handful of people will sit around deciding what’s good for us. But even if this is not to be the case under the Warren plan, what would be clear, as is the case in the UK, is the growing pressure from the fact that in aging populations, healthcare consumes an ever-increasing percentage of GDP.

But suppose that Warren gets her way. Suppose that we have a single-payor plan along with a simple cap on the annual increase in healthcare expenditures, say to the level of inflation. At first, if there is truly so much administrative waste in the system (and ignoring all of the other possible side effects such as doctors leaving the field in droves) things might seem better.

But over time, as the waste is squeezed out, the absolute cap on spending growth will bite. Then measures of effectiveness will be necessary to screen new technologies to ensure that they are in fact relatively ‘cost-effective.’

This is not an argument for the very squishy estimates of Quality Adjusted Life Years employed outside of the US. The highly questionable science underlying these estimates hasn’t stopped the WHO and various other famous economists from justifying high levels of healthcare expenditures. As well, attempts to employ a clear threshold to deny funding for a particular treatment serves to give advocates a target.

The point is this: Perhaps the most effective, and only, way to both control the growth in healthcare spending and retard the constant creep of technology is through an absolute growth cap. If there is a good that folks want and a very ineffective cap on how much of that good will be consumed, then the demand for the good will result in ever increasing expenditures. So just put a cap on it. And the only way to do this is to adopt a single payer system.

* * *

Postscript

Adam Gaffney, in an article published in the Boston Review makes similar points to those made here but Adam’s is both a better constructed and more thoroughly researched article that cites economists not mentioned here. 4

I was most interested in the basic raw arguments made way back in the literature where you can feel the underlying ideological battle between free marketers and those who saw the need for a different path for health care. After all, the idea of universal healthcare is commonly attacked with language such as ‘don’t let healthcare be socialized.’

Kenneth Arrow, arguably an economist more famous than any so far mentioned, published an essay in 1961 in which he outlined the challenges of pulling health care fully into a market economy: Not all aspects of health care can be priced and some aspects, such as the idea that health care is a merit good – something for which there is a collective willingness to underwrite – means that health care will suffer from a continuous cycle of policy interventions followed by market forces discovering the unintended consequences of those interventions. 5

You can see Arrow’s argument at work in the Affordable Care Act (ACA.) Mandating that an indication for which there is at least one treatment be covered under the act has given an increasingly fractured biopharmaceutical industry increased pricing power.

Especially in the field of oncology, progressively smaller firms have raced to market with marginally beneficial treatments at ever increasing prices such that the cost of a QALY in oncology treatment has significantly increased. In other words: Under the ACA, it appears that drugs with marginal benefits have gotten way more expensive. 6

In summary, this essay is a relatively unimportant contribution to the school that believes that the trend in health care spending cannot be changed by tinkering from within. No amount of tweaking of incentives will help. This is made clear by a scan of fifty years of headlines from the economic literature. Elizabeth Warren is (was) right.

References:

- The Welfare Loss of Excess Health Insurance, Martin S. Feldstein, The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 81, April 1973

- Health as Human Capital: Synthesis and Extensions, Gary S. Becker, Oxford University Press, 2007

- The Health Care Quadrilemma: An Essay on Technical Change, Insurance, Quality of Care, and Cost of Containment, Burton A. Weisbrod, Journal of Economic Literature, Volume 29, Issue 2, June 1991

- What the Health Care Debate Still Gets Wrong, Adam Gaffney, Boston Review, October 2019

- Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care, Kenneth J. Arrow, The American Economic Review, Vol. 53, Issue 5, December 1963

- Insurance and the High Prices of Pharmaceuticals, Besanko, Dranove and Garthwaite, NBER working paper 22353, June 2016