by Bill Murray

This is Part Two in a series. Read Part One here.

Sooner or later even the best laid plans come full stop at the bureaucrat’s desk. At the entrance to Ngorongoro crater, Tanzania, we pull up short at a moldy branch of officialdom, no less out of place than some forlorn Chinese outpost on the Tibetan steppe. This requires twenty minutes of perfunctory paperwork, at night.

Stamp pads come out, ledgers are opened, numbers and details are transcribed and we will not proceed until the clerks accede. Which finally they do.

Difficult to get our bearings, arriving in the dark. There is only the tiny new moon that heralded Eid-al-Fitr, the end of Ramadan, and there are no lights out there because there is nothing built in the crater. We gaze into the gaping chasm for a while and then go off to eat.

I don’t know about this place. The restaurant is thatch-roofed, and the sound of gentle rain is comfy, but it’s scary how big and full the dining room is.

“We have more than 140 guests,” The server beams. I stare into my rice.

You want to be the only ones, the wilderness, the animals – Africa! – all to yourself. But this place is not like that.

Still, the shower is hot and a candle is provided. Alongside the candle is a matchbox with two, count ’em, matches. “Cleanext” brand tissues. Power goes out sometimes. Then it’s so dark you can’t even begin to see a thing outside. Not one thing. Anywhere. Clouds cover the little moon. Just 100% dark. Totality.

•••••

We begin in morning rain, anxious, our first venture over the crater rim into the wildlife. Over many years to come and many different experiences, immersion in African wildlife will fill our hearts. This is the first trip together into the bush for Mirja and me, in the 1990s. Our eyes are wide open, we are a little frightened and a lot giddy, utter novices.

On the drive in from Arusha yesterday, Godfrey reached into a nest of papers on the seat next to him and handed Mirja a paper describing our mission:

SATURDAY: After breakfast descend into the crater in a 4-wheel drive vehicle. Soon the dotted black spots you have been seeing from the topturn out to be herds of animals Picnic lunch by the Stream. In the afternoon, after a magic day, you return to NGORONGORO SOPA for dinner and overnight.

SUNDAY: After breakfast descend into the crater in a 4-wheel drive vehicle. Soon the dotted black spots you have been seeing from the topturn out to be herds of animals Picnic lunch by the Stream. In the afternoon, after a magic day, you return to NGORONGORO SOPA for dinner and overnight.

MONDAY: After breakfast descend into the crater in a 4-wheel drive vehicle. Soon the dotted black spots you have been seeing from the topturn out to be herds of animals Picnic lunch by the Stream. In the afternoon, after a magic day, you return to NGORONGORO SOPA for dinner and overnight.

TUESDAY: After breakfast, descend into the crater in a four-wheel drive vehicle for AM crater tour. Then ascend again from the crater. Lunch enroute then drop off Nairobi.

KARIBU TENA TANZANIA

•••••

Because the animal world is crepuscular – active at dawn and dusk – the convention is morning and afternoon safari activities each day (driving, walking, canoeing where appropriate), when the animals are moving around on the hunt.

Ngorongoro is different. The crater is so big that once you’re down inside it’s probably better just to stay. Godfrey brings pre-packed lunches and we hit the rim road to make a day of it, in search of dotted black spots.

Acacia forest forms a thick umbrella. The downward slope opens into a sea of sorghum apples, 3/4 inch yellow balls on bushes. This is rhino food, only plentiful up here nowadays, the rhinos having eaten this year’s crop down on the floor.

The first animals out on the plain are buffalo. Three, then three more, then dozens. You stare at them, they stare back at you and never miss a chew of grass. They’re caricatures of British barristers, seems to me, wide horns and white on the top of their heads like powdered wigs.

A handful of Grant’s gazelles stands alert, gold with a sporty black racing stripe down each flank, black tail and white backside, with lyre-shaped, ringed horns. These antelopes live among the herd, in the open. They need plenty of room because their only weapon, really, is their speed. The deer of the plains.

Silver-back jackals slink along low to the ground, eyeing the gazelles, skulking, guilt built into their carriage. Unlike the gazelles, whose only medium-term relationship is between mother and offspring, jackals mate for life, and hunt singly or in small groups. They’re scavengers. Like hyenas, unless they’re in a pinch they wait for others to do the dirty work.

Silver-back jackals slink along low to the ground, eyeing the gazelles, skulking, guilt built into their carriage. Unlike the gazelles, whose only medium-term relationship is between mother and offspring, jackals mate for life, and hunt singly or in small groups. They’re scavengers. Like hyenas, unless they’re in a pinch they wait for others to do the dirty work.

A helmeted guinea fowl runs by, just a scream of a squat little bird. She’s like our Appalachian peahens except with a flamboyant blue head. Unless you begin with an affinity for the avian, birds are a taste acquired with time in the bush. Your initial brochure-induced yearning to see the “big five” — buffalo, elephant, leopard, lion and rhino — brushes bird life aside, but the utter diversity of the avian world here is astonishing. Some 300 migratory species pass through the crater.

Up on a rise, white European storks preen before a wildebeest pack. They hang around shallow lakes and lagoons all across sub-Saharan Africa. Their special trick is to stir up water with one leg to flush out meals and nab them with their long bills, fine tools for fishing.

Objectively, they present as ungainly and absurd predators, calling down doom on hapless crustaceans, small fish, frogs, from the heights afforded by implausible, reedlike legs. These storks will soon be leaving for the long flight north, to breed in the northern spring and summer.

It’s most remarkable how they get there. Not fond of wing-flapping, the migratory stork prefers to ride thermal air currents high into the air and glide from one to the next and the next. Since thermals form less readily over water, they fly entirely around the Mediterranean on their way to and from Europe. You’ll thus see migrating storks over the Levant, or the Strait of Gibraltar.

We stand in the pop-top to survey 60 or 80 wildebeests, each an ungainly mix of ox, antelope and horse. Godfrey reckons this herd (which passes through and doesn’t live exclusively in the crater) at about 1.6 million strong, but he says fully a quarter may die in their annual migration. Looks like they replenish themselves fast. There are more moms with kids here than anyone else.

They sound like sheep on testosterone.

One side of the hill asks a question, “Mmmmmm?”

The other side answers, “Mmmmmm.”

Zebras mix with the wildebeests. Here they stand, shaking and twitching like neurotics. They get the Most Dispirited-Looking Beast Award. The little ones, even some of the bigger ones, have an unfledged, unbecoming brown fuzz.

Zebras mix with the wildebeests. Here they stand, shaking and twitching like neurotics. They get the Most Dispirited-Looking Beast Award. The little ones, even some of the bigger ones, have an unfledged, unbecoming brown fuzz.

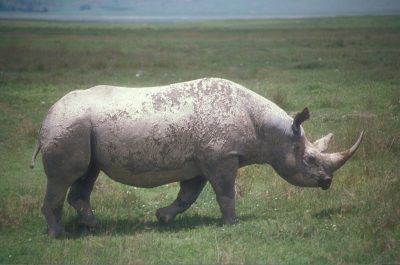

Now and again Godfrey pulls the Land Rover up short, grabs his binoculars and peers into the distance. Sometimes he turns off the engine to steady his view. It’s how we find two of the 24 black rhinos in the crater. This really excites Godfrey, though they’re only lying there sleeping. In fact, every time we see rhinos, ever, Godfrey stops before them to rhapsodize.

Rhinos are perfectly prehistoric, it’s true. With that unicorn horn they’re a fable, your perfect living dinosaur. Implausible. Three toes on each foot, they’re “odd-toed ungulates.” Everything about them is odd. My guess is carrying around all that armor makes them lethargic. They seldom do anything at all beyond giving the grass a desultory graze.

The biologist Richard D. Estes believes giraffes return your interest the least of all the animals, usually just staring back at you. They can do that, I guess, from such a lofty remove (I wrote a whole 3QD column in 2018 about giraffes here). Maybe rhinos’ armor makes for invulnerability, I can’t say, but I nominate these guys for the disinterest prize.

Which is good. They’re known to charge arbitrarily, perhaps because of their poor eyesight. When they do, they lower their heads and charge in a gallop that can reach thirty fearsome miles per hour.

A warthog skitts by in front of the Land Rover. They are irretrievably shy and self-conscious, with good reason. Jackals harass them as a hobby. Like wildebeests, it’s as if they’re committee-built, with the mane of a horse, eyes of a pig, a nasty rat’s tail, and horns nobody else would claim. A welter of scattered whiskers, bristles and “warts” of thickened skin and gristle, with a snout used as a spade to shovel for food and to burrow for protection against predators.

A warthog skitts by in front of the Land Rover. They are irretrievably shy and self-conscious, with good reason. Jackals harass them as a hobby. Like wildebeests, it’s as if they’re committee-built, with the mane of a horse, eyes of a pig, a nasty rat’s tail, and horns nobody else would claim. A welter of scattered whiskers, bristles and “warts” of thickened skin and gristle, with a snout used as a spade to shovel for food and to burrow for protection against predators.

Yet it is untrue that only a mother could love the warthog. Males stay up late after dark during rutting season to sniff out burrows that hold females, and return to jump those girls when they emerge next morning.

Just up the road, conflict: Three jackals slowly circle a mom and a newborn wildebeest that can’t much more than wobble. If the jackals can separate it from it’s mom, well, even a jackal might kill this little guy. Three feet tall and all legs, it cowers under its mother. She chases one jackal and the other two approach. Raw life theatre plays out for a time, but it all ends happily for the wildebeests when the whole mini-herd picks up and moves, leaving the jackals empty-jawed.

•••••

From inside, the rim of the crater presents one continuous mountain ridge. It’s blue as the Blue Ridge mountains, the floor dull green and Kentucky bluegrass purple. Clouds nibble at the rim top. Everywhere, tiny butterflies work patches of white and yellow wildflowers. A Thppping sound rises from the grass, from grasshoppers; birds give concerts.

A gray-headed heron forages for food. Moving its neck ramrod straight up and then undulating so that poor doomed insects must think it’s a huge snake, it spears and chomps on grasshopper after grasshopper. There is unlimited feed.

While Godfrey loves rhinos, he also likes the decision to go home. Every morning when the air is crisp and the angle of the sun low, we set out, open-top, in an agreeable amble down into the crater. But when it’s time to go home Godfrey rattles butts to climb the crater wall as fast as he can. He flies up the hill to the lodge.

The bar has picture windows and warmly upholstered overstuffed chairs. Outside sliding glass, the grass is clipped high and thick, and huge birds turn over the bottom, 610 meters down. The sun slants in, about to slip behind clouds then behind the rim of the crater.

“Pilsner Lager” Kenya beers are served, there’s a full day’s game viewing behind us and no U.S. politics, no celebrity scandals. It’s liberating, thrilling.

•••••

Cirrus clouds drift far above the rim. Just beyond the lodge, a lioness sits atop the carcass of a wildebeest. Her breath still heaves; this must have just happened. Three individual wildebeests watch and mourn respectfully at distance, a macabre death escort. But the cat is not hungry. She sits still and glowers.

Across the plain wildebeest and zebra moms play easily with their offspring and good humor reigns until we drive right into a lion hunt. Godfrey stops. Two lionesses cross left to right, one trailing the other by thirty yards, both padding low to the ground. The herd scatters save for a few wildebeests in the vanguard, whether by design or stupidity, I can’t say.

Stalking predators focus on a young, ill, injured or weak member of the herd, picking out an animal at a disadvantage. Once they isolate their victim, all the cats kill by suffocation, jaws to the throat so their prey’s windpipe is crushed.

The lionesses’ clear designs on the wildebeests, and the wildebeests’ clear receiving of the message, are high drama, slowly unfolding. In this case the lionesses judge a kill not worth the effort and finally lay down for a nap.

Much as you might suppose the contrary, lions are not prodigious lovers. So happens it’s mating season and lion couples lay about, paired off. The act doesn’t last long, it’s done quietly, and the male climbs down and both roll over to sleep it off. This may repeat every fifteen minutes, but they appear to relish the naps in between just as much.

Much as you might suppose the contrary, lions are not prodigious lovers. So happens it’s mating season and lion couples lay about, paired off. The act doesn’t last long, it’s done quietly, and the male climbs down and both roll over to sleep it off. This may repeat every fifteen minutes, but they appear to relish the naps in between just as much.

Once mating is over they split. New mothers don’t want anything to do with males until they’ve raised their cubs and sent them off, because males will kill cubs in competition for the female’s undivided attention come next mating season.

A helmeted Guinea fowl comes busily clucking out of the brush and sees lions too late. Rather than retreat, (she’s gone too far by now), she assumes a cocky strut and clucks all the more furiously as she accelerates on by, fast as her spindly little legs will churn.

“Jeez, lions!” you can hear her thinking. Ayeee!

We take a long drive over to the hippo pool. This is a favorite place for jeeps to get stuck in the mud. Two got stuck the day before and Godfrey’s tow rope saved the day.

You have to be patient at the hippo pool, because nothing much ever happens. Most of our fellow safariers aren’t patient. They roar up, sit awhile, and roar off, including one particularly irritating couple with their own jeep, who leave their diesel idling and music on the whole while. We remain patient and we’re rewarded with those photogenic, wide-open hippo yawns.

Dust devils kick up on the other side of the plain, mini-tornadoes of swirling sand and dust. At the same time, thunder crackles across the crater and a storm looms up on the rim, even as we’re topping off our sunburns down on the crater floor.

We’re about to turn and climb to the rim when Mirja spots something way in the distance, to the west around the pond. Could be a rhino, zebra, wildebeest or lion, since these are the animals big enough to appear as little dots across the plain. But this is different, curiously shaped. It’s taller than the pack animals, but there are no giraffes in Ngorongoro.

Godfrey grabs the binoculars and all at once we all gasp, “It’s a man!”

Two other jeeps make the same discovery and all of us hurtle over to save this daredevil fool. Lions, even hyenas could’ve attacked, but whoever this man is makes it to the first arriving jeep. Turns out his jeep was stuck and, getting on in the afternoon, he was afraid his passengers would have to spend the night if no one else happened by, so he decided to chance it.

There’s a lot of relieved joking and laughter. He points to the tiny distant speck that is his jeep. Must’ve walked a couple of kilometers unarmed through the grass.

Twice separately today, solitary rhinos start out as mere motes and grow to rather like propane tanks from a distance – long, round, gray and dusty.

Normally rhinos remain far enough away to look like propane tanks, because they don’t walk around much. Both times today, though, these rhinos are on the move, busy marking territory, and the tanks get bigger and closer and in five minutes they’re walking straight across the vehicle tracks, twenty feet away.

Normally rhinos remain far enough away to look like propane tanks, because they don’t walk around much. Both times today, though, these rhinos are on the move, busy marking territory, and the tanks get bigger and closer and in five minutes they’re walking straight across the vehicle tracks, twenty feet away.

They continue on and for ten more minutes grow smaller and smaller until they’re specks in the other direction. The rhino is so massive, its merely walking by is a statement.

The sky has never been bluer. There’s a breeze. Brilliant yellow birds cackle and fill a tree. There is at first just a small shower on one edge of the rim. Tiny wildflowers cover the crater floor.

Everything is bigger than life out here, and even when you’ve gotten used to the idea of eating lunch by a pond inhabited by four-ton hippos, suddenly the crack of thunder past the rim rivets your attention on monstrous nimbus the color of a bruise, burgeoning upward, gobbling the sky, and fifteen minutes after the sky had never been bluer, terrific thunderheads loom over Ngorongoro.

The prevailing winds are in from the Indian Ocean, so the eastern wall of the crater acts as a windbreak and the east rim gets more rain than the west. It looks for a time like we’ll all be drenched. Ngorongoro is so big, though, we never feel a drop even as the far side of the crater sinks into morass.

Lionesses again approach a wildebeest herd. They alternate, two together with one executing a slow flanking action first to one side then the other, pausing to lie low in the grass for ten minutes at a time.

When they become too tiny to follow even in the binoculars, they’re still a distance from the pack, and we leave that last chapter unfinished and bump on home. A n agreeable end — you write your own.

•••••

Photos from my website, EarthPhotos.com.