by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

1.

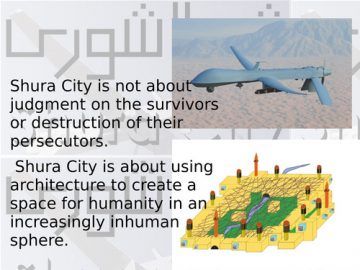

It was at the height of Obama’s massive acceleration of George W’s drone program, when city planner Asher J Kohn began imagining his drone-proof “Shura City.” He did this, he said, “Out of the realization that the law had no response to drone warfare.” And so he came up with his concept of Shura City, ostensibly in the hope that by rendering military drones less efficient for “apprehending” targets in the Middle East, the US would be forced to return to police actions under international law.

The reaper drone that carried out the killing of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani on January 2 was part of a military program that had its origins in the pilotless hot-air balloons the Austrians used to bomb Venice in the late 19th century, as well as experimental remote control airplanes developed in the First World War. But, in terms of application and ethical issues, they are mainly seen as an extension of the aerial bombing campaigns of WWII.

Aerial bombing was a game changer in war: no longer would the world watch as two armies faced off on a battlefield–for the future was of indiscriminate bombing of cities from above. The line between combatant and non-combatants was effectively blurred forever with aerial bombing –and, not surprisingly, civilian deaths skyrocketed.

When viewed from this history, targeted drone strikes seem a natural and more efficient way to kill an enemy.

Many international law experts, however, disagree. This is based on modern theories of Just War, which generally views the use of drones ONLY acceptable if there is a clear imminent danger (must be transparent and defensible) and if capture is feasibly impossible. Without evidence to the contrary, Trump’s killing does not appear to be just. Of course, Soleimani is a bad guy. We have been informed that he was actively plotting against us. But without evidence, this is too ambiguous to meet the demands of imminent danger. I would cede impossibility of capture– not because it is bodily impossible –but would have been akin to kidnapping and therefore politically impossible. But that should also make one think: if we can’t grab him for political reasons, then why can we kill him?

Many international law experts, however, disagree. This is based on modern theories of Just War, which generally views the use of drones ONLY acceptable if there is a clear imminent danger (must be transparent and defensible) and if capture is feasibly impossible. Without evidence to the contrary, Trump’s killing does not appear to be just. Of course, Soleimani is a bad guy. We have been informed that he was actively plotting against us. But without evidence, this is too ambiguous to meet the demands of imminent danger. I would cede impossibility of capture– not because it is bodily impossible –but would have been akin to kidnapping and therefore politically impossible. But that should also make one think: if we can’t grab him for political reasons, then why can we kill him?

But let’s choose to believe for a moment that this is not another case of imaginary weapons of mass destruction and that there was credible evidence of an imminent concrete threat. Well, I would say that MUST be presented to congress–otherwise, we are continuing a situation–begun in a small way under Bush and in a big way under Obama– of giving a president the power to kill without even the checks and balance of the other branches of government, much less the public.

2.

2.

It’s true, we are being told, countries no longer declare war on each other, and instead –thanks to the US turning the Middle East into borderless counterterrorism battlefield– engage in subtler forms of attack to defend and promote their interests. So doesn’t it follow that we now need new rules for this new world of extra judiciary killings, assassinations, and infrastructure attacks from afar?

At the very least, congressional oversight and a renewal of what it means to be an expert is necessary.

On this latter point, Columbia University historian Manan Ahmed –years ago in 2011– studied the profiles of those who are deemed “experts” and invited to the halls of power in the US to ply their craft, to understand and arrive at an ideal type that the official point of view considers an “expert.” And it’s not a pretty picture:

Such an “expert” is usually one who has not studied the region, and especially not in any academic capacity. As a result, they do not possess any significant knowledge of its languages, histories or cultures. They are often vetted by the market, having produced a bestselling book or secured a job as a journalist with a major newspaper. They are not necessarily tied to the “official” narratives or understandings, and can even be portrayed as being “a critic” of the official policy. In other words, this profile fits one who doesn’t know enough. Rory Stewart and Greg Mortensen are examples of a particular type of expert – “the ‘non-expert’ insider who can traverse that unknown terrain and, hence, become an ‘expert.’”

He called this, in his article in The National, “Flying blind: US foreign policy’s lack of expertise American spy technologies gather intelligence in vast quantities, yet US foreign policy is rife with unqualified pseudo-experts. To know or not to know? This is the great conundrum of empire.”

(Here is a more recent take on this issue with a specific focus on “Iran experts.”)

I don’t see there is any turning back–is there ever in turning back?

3.

3.

This is what was so interesting about Kohn’s “drone-proof city” idea, since it aimed to change policy by undermining the effectiveness of the drones themselves.

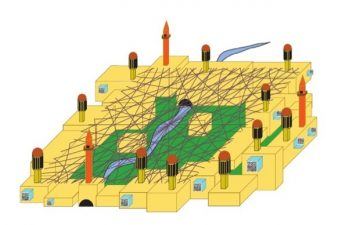

His was a take on a “gated community” –and yet the gates are not to keep people out, but rather to render all the people living within its walls unidentifiable and anonymous. So in the same way that a medieval castle fortress was an architectural defense against 15th and 16th century artillery technology, so too does Shura City seek to use architecture as a defense.

This new-style defense, though, “is not defense-through-hardening,’ he says, “but defense-through-confusion.”

His architectural plan has several features–all which are seen to enable this style of “defense-through-confusion.” People dwell in Habitat ’67-style stacked dwellings, which make mapping and the tracking of residents’ movements difficult. There is a protective shared-roof covering to the community, which further protects against aerial

tracking.

The apartment-style dwellings make use of smart windows, which utilize technology to render the glass easy to see out but prevent peering in. Focusing on windows, which are, after all, one of the weak links in security against drones, he envisions something like the exquisitely intricate windows at the L’Institut du Monde Arabe, in Paris:

Patterned after amashrabiya, a feature of Arabic architecture that protects from glare and prying eyes. In Paris, the machines dilate and contract, forming new patterns and shut-ting down for closed exhibits. These are obviously good for keeping what’s inside from being known outside.

An alternative to patterned windows is changing color glass, which would also serve to allow light in while preventing easy identification or tracking of the residents from above. The windows in effect are contributing to bringing people out of a siege mentality. We read every so often of how it feels to be on the ground in Pakistan and Yemen, where the drones seem ever present. The psychological effects are profound, and Kohn’s imaginary city is designed to undermine the rationale of the technology.

Would it work?

Would it work?

All-in-all, Kohn’s “drone-proof” city is reminiscent of Norman Foster’s famous project in the desert of Abu Dhabi, Masdar City. Also designed from scratch, Masdar was planned to be the world’s first zero-carbon city– and its plan employs many of the same architectural elements of Shura. However, in Masdar’s case, these similar architectural elements are not for defense, but rather for ecological reasons. I worked on a translation of a Japanese article about the city and became fascinated by its concepts.

According to the original plans, in Masdar citizens will dwell in stacked housing units surrounding covered plazas. Everything about the construction enable the regulation of temperature and maximizing environmental performance. In addition to a shaded city, transportation takes place below ground to create a truly walkable city–something unheard of in many places in the world.

And, while Kohn’s Shura City made use of a lattice style roof based on NEY +Partner’s project for the Netherlands Maritime Museum, Masdar planned for gorgeous solar umbrella shades.

And, while Kohn’s Shura City made use of a lattice style roof based on NEY +Partner’s project for the Netherlands Maritime Museum, Masdar planned for gorgeous solar umbrella shades.

At Masdar, a variety of towers (minarets) and wind-catchers (badgirs) are also used in along the perimeters to both regulate temperature and undermine aerial heat-mapping.

4.

Kohn’s project was just a proposal. Or really, a dazzling provocation.

Kohn’s project was just a proposal. Or really, a dazzling provocation.

And, while it is bare-bones, still there are two things that I think could immediately be said about the implications of “defense-as-confusion.”

First, it brings us back to a state where we are living with our fates tied together. Like in the old Japanese han (班) system, because an attacker would be forced to destroy the entire compound rather than only the militants, we would truly have to become our brother’s keeper. This might be anathema to Libertarians and yet to those interested in getting back to more communitarian values, it is of interest–as it would theoretically encourage stronger communities.

Whether for security or for ecology, it seems like we are just going to have to go back to a more community-oriented lifestyle.

Second, experts tell us (and indeed it is a no-brainer) that the arms race for this kind of cheap and low level technology will be such that it’s only a matter of time before everyone has drones. If this is the “next arms race,” it will be a very different one fro the nuclear club –which so far has required governmental level initiation. Drones are a different kettle of fish; for in the words of the Brookings Institution expert Peter Singer:

This is a robotics revolution, but it’s not just an American revolution — everyone’s involved, from Hezbollah to paparazzi.

It is, therefore, simply inevitable that, even if not for environmental reasons alone, we will have to alter the way we live. Not just in terms of architecture– but in terms of community and communal responsibility. If not for defense against drones, then for ecological reasons.

I can’t help but think of Rene Girard’s words that, History is a test. And Mankind is failing it.

That about sums it up I guess…

++

For my bibliophile friends (he knows who he is): My Top Reads of 2019