by Dwight Furrow

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists went so far as to call wine writers “bullshit artists”. (The feeling is mutual.)

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists went so far as to call wine writers “bullshit artists”. (The feeling is mutual.)

Even the sommelier-trained author of the bestselling book Cork Dork, Bianca Bosker, has reservations about the accuracy of such language. After taking writers to task for using terms such as “sinewy” and “broad-shouldered” she writes: “It seems possible that what we “taste” in a fine wine isn’t so much its flavor as the qualities of good taste that we hope it will impart to us.” She seems to be suggesting that wine writers just make stuff up to sound impressive.

The general objection is that these descriptors are metaphorical and are therefore too subjective and ambiguous to give readers an accurate, verbal portrayal of the wine. However, these complaints are tilting at windmills.

We cannot avoid using metaphors to talk about wine because there is no adequate, literal vocabulary that can replace them. Even the commonly used and widely accepted fruit, vegetable and earth descriptors that have now become standard in the wine industry are metaphors. Cabernet Sauvignon from some Napa Valley vineyards often smell like black cherry. But, of course, Cabernet Sauvignon is not literally a black cherry. It may smell vaguely like a black cherry but the word “like” there is the tell. “Black cherry” aroma in a wine is a likeness, a metaphor useful for approximating the aroma of some Cabernets. With the exception of “grapey”, no fruit descriptor we use to describe wine is close enough to its source, i.e. the actual fruits, to count as a literal description. The same is true of “mushroom” to describe Pinot Noir or “smoky” to describe Syrah from the Northern Rhone in France. These descriptions have become so commonplace that they are no longer treated as figurative just as “that is a deep problem” or “a road runs through my property” are considered literal even though they started out as metaphors.

We compare wine aromas to fruits and other edible substances because these are the most easily recognized source domains for useful metaphors describing wine. However, if metaphors based on fruits and vegetables are appropriate for describing wine, why not metaphors from other source domains? Critics of our wine vocabulary need some additional argument to rule out source domains such as “wine is like a body” or “wine is like a person”, from which “sinewy”, “broad-shouldered” or “brooding” are drawn. Thus, if there is a problem with our current wine vocabulary that would justify these complaints, it cannot be that the vocabulary is metaphorical since the fruit and vegetable metaphors are now widely accepted; it must be that certain other source domains for metaphor are inappropriate when describing wine.

It is worth pointing out that a scientific vocabulary will not come close to usefully describing a wine outside the laboratory or the production area of a winery where highly technical discussions of odor compounds are necessary. It’s fine to point out that a wine has a distinct odor of pyrazines laced with hints of thiols. But pyrazines can smell like bell pepper or olive, thiols like grapefruit or gooseberry. And those differences matter aesthetically. To claim that a Sauvignon Blanc contains pyrazines is almost tautological; that aroma is part of what defines Sauvignon Blanc. That is far too generic a description to be useful to readers of wine reviews who want to know the relative virtues of a specific wine.

What the reader needs to know is how the aroma and flavor notes are working together to create an overall impression of the wine. No list of chemical compounds or aroma esters will give you that. Chemical compounds don’t exist in isolation; they interact with other compounds to form emergent properties such as harmony, explosiveness, finesse or flamboyance; these are not reducible to underlying chemical properties. It is these emergent, aesthetic properties that we enjoy, and any description that leaves them out will be misleading. More importantly, even the metaphorical fruit and vegetable aroma descriptors give us only limited access to what makes a wine enjoyable. If you enjoy Cabernet Sauvignon from Napa it probably isn’t because you have a particular fetish for black cherry aromas. Wine writers need a more robust vocabulary if they are to do their jobs and it will inevitably be both metaphorical and one that can indicate the overall aesthetic virtues of particular wines.

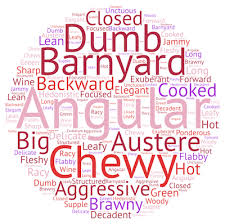

Perhaps then the problem is with some of the other source domains that wine writers use in their tasting notes. It is with regard to the texture and mouthfeel of wine where the terminology becomes even more explicitly metaphorical although some of these metaphors are also so familiar they have become conventional elements of our wine vocabulary. We routinely speak of wines as having length, as caressing and round, as assertive or having an acid kick, as languid or soft as if these were literal descriptions. Of course, we are in even more obvious figurative territory when tasting notes include reference to a wine’s personality as sexy, brooding, reserved or exuberant. “Wine is a person” is perhaps the most ubiquitous source of metaphor to describe the distinctiveness of a wine and probably the source domain that provokes much of the consternation.

The iconic wine writer Robert Parker, Jr. was notorious for his florid tasting notes. Here is one noteworthy example:

[T]he 2001 Batard-Montrachet offers a thick, dense aromatic profile of toasted white and yellow fruits. This rich, corpulent offering reveals lush layers of chewy buttered popcorn flavors. Medium-bodied and extroverted, this is a street-walker of a wine, making up for its lack of class and refinement with its well-rounded, sexually-charged assets. Projected maturity: now-2009.

The reference to “street-walker” might strike one as over the top, although Parker clarifies what he means in the tasting note. It seems to me rather obvious what Parker is intending with this description—some wines have pumped-up flavors that are overtly hedonistic but lack finesse. It isn’t obvious why “wine is a person” is less useful that “wine is a fruit” as a source of metaphor.

In my posts here at 3 Quarks Daily, I’ve been giving an account of wine appreciation in which tracking distinctive variations, the surprise of unpredictability, and a provocative, affect-laden sensory experience are fundamental to what we love about wine. Finding a way to communicate that experience is essential to the health of the wine community. However, describing this kind of aesthetic experience that wine makes available poses a daunting task for wine writing and wine criticism. Wine writing that purports to aid in wine appreciation must (1) describe the individuality of wines and capture the full range of their expressiveness, and (2) be on the lookout for novel variations that are aesthetically meaningful.

This is a daunting task for several reasons. As many have noted, in Western culture we lack a fully developed vocabulary for describing sensory experiences. Furthermore, all language is built on conventions and general concepts and thus describing something that is both new and unique requires some degree of linguistic innovation. The conventions of language must be stretched to accommodate something that by definition doesn’t quite fit those conventions. Neither of these requirements can be thoroughly satisfied by using generalities referring to what is typical of a wine region or varietal. Yet, if the writer is to be understood, those novel descriptions must remain sufficiently bound to conventions to be grasped by the reader. That is the dilemma—to be creative yet conventional.

In most contemporary wine writing, the problem of describing the individuality and uniqueness of a wine has been solved by focusing on a winery’s story. The path to quality winemaking is often circuitous, full of problems to be confronted, and requires vision, courage and dedication. Winemaking is usually a story about the uniqueness of a place and if the personalities and traditions behind the wine are also distinctive that may go some way toward explaining the distinctiveness of the wine. The individuation and novelty of the wine is captured by the individuality and novelty of the story behind it. This is a reasonably successful strategy—we love stories, and when they are about places and people, uniqueness and individuality can be evident in the unfolding tale.

However, there are limitations to this approach. The features of the wine itself may slip into the background, especially those holistic properties to which descriptions of aesthetic attention must point. The distinctiveness of a winery’s story may have some aesthetic appeal on its own since narratives can be aesthetic objects. But the wine itself is the primary locus of aesthetic attention; if the wine is not distinctive, the aesthetic appeal of the winery’s story is diminished. Secondly, there are many outstanding wines that are blends of grapes from several vineyards, in some cases, several regions. Thus, they lack the sense of place that is seemingly required by a compelling backstory. Furthermore, many wineries that make compelling wines lack a long and storied tradition and their owners and winemakers walked a conventional, unremarkable path toward their achievement. In other words, what is distinctive is their wines, not the story behind them.

The stories of place and struggle are an essential part of wine discourse; the wine world would be a poor place without them. The historical story often plays a central role in explaining the appeal of a wine. But telling that story cannot replace the need to describe and evaluate what is in the glass. In the end, this fascination with stories, to the extent they replace a concern for what is in the glass, will not serve wine culture well. We drink wine to enjoy flavors and textures; we have other media for telling stories. Nothing can replace the need for compelling tasting notes.

Thus, we need to investigate how well elaborate metaphors serve the goals of wine criticism. To answer that we need an account of what the goals of wine criticism are as well as an account of how metaphor works to advance those goals. Are some metaphors better than others? What makes them so? How do readers know what wine metaphors mean? And how best can we teach them what they mean?

Next month I will begin to answer those questions.

For more on the aesthetics of food and wine visit Edible Arts or consult American Foodie: Taste, Art and the Cultural Revolution.