by Rafaël Newman

When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.

When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.

The Nobel Committee, according to Gomringer, had thus acknowledged the primordially hybrid nature of literature, the inextricable relationship between sound and sense, meter and message that had from the outset refused to differentiate between music and verse, but rather had created the two simultaneously, a marriage of the Apollonian and the Dionysian that would be variously contested by purists in subsequent generations, but would never entirely disappear.

The Academy’s own rationale for its choice in 2016, however – that Dylan was distinguished “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition” – proposes a slightly different account of the intervening literary history, and a different agenda: an existing musical idiom, it suggested, had been revitalized by the advent of a novel lyrical form.

This turned the conventional hierarchy, as ventriloquized by Gomringer, on its head: rather than a frivolous poem being rewarded with ennoblement in song for its having been “especially well made”, it was a venerable musical tradition, in the Academy’s account, that was offered new life by verse. It was as if Nietzsche’s proposition had been overturned, or at least supplemented: instead of tragedy born out of the spirit of music, we now had music reborn out of the spirit of lyric poetry.

For the past few years, a troupe of performers – classically trained singers and pianists, together with two “dramaturges”, or presenters – have been helping to foster just such a rebirth, in Switzerland and the regions just across its borders. The ensemble, Besuch der Lieder (besuchderlieder.net), which means “The Company of Song” but is also a play on Buch der Lieder or “Book of Songs”, the title of a celebrated collection of poetry by Heinrich Heine, was founded by Edward Rushton, a British-born composer and concert pianist who now makes his home in Switzerland.* The troupe’s aim is to perform Hauskonzerte or “house concerts”, recitals held in the homes of private individuals for the friends and family of the hosts, featuring exclusively Lieder, art songs or chansons of the 19th and 20th centuries, for voice and piano. Such songs typically feature a lyrical text by a poet, often but not always of some renown, set to music by a composer, frequently a contemporary of the poet’s.

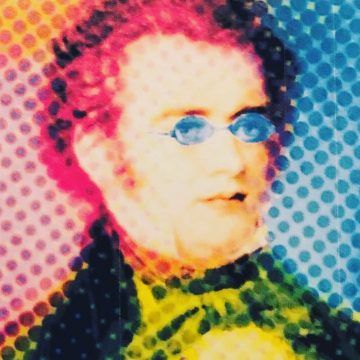

The ensemble staged its first performance – two performances simultaneously, in fact, in two separate venues in Switzerland – on January 31, 2016, the 219th anniversary of the birth of the Austrian composer Franz Schubert. The date was chosen deliberately, as were the programmes for both house concerts, consisting entirely of works by Schubert; for although the composer lived only to the age of 31, he managed to produce more than 600 Lieder (which were in turn only a portion of some 40 volumes of collected works), making him the godfather of romantic art song, a veritable Hank Williams of the Biedermeier period. And although the ensemble regularly performs house concerts that include songs by many other composers – among them Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Peter Warlock, Darius Milhaud, Fanny Mendelssohn and Hugo Wolf – Schubert’s mastery of the genre, combined with his sheer ubiquity in the corpus, makes him a recurrent feature of programmes.

Schubert set to music texts by poets both illustrious – Goethe, Heine, Klopstock – and less well-known, including personal friends of his. It was one of these, Franz von Schober (1796-1882), who contributed the “lyrics” to Schubert’s perhaps single most renowned song, “An die Musik” (“To Music”, 1817), a succinct paean to the charms of one art offered by a practitioner of another:

How often hast thou, gracious art,

When savage life had caught me in its net,

A love within me stirred to warm my heart

And salvaged me from this world to a better yet,

From this world to a better yet!

Oft has a sweet and sacred chord of thine array,

A sigh, escaped from out thy harp to me,

And bared a heav’n of hope for better days:

Thou gracious art, for this my thanks to thee,

Thou gracious art, my thanks to thee!

Schubert’s dignified setting of von Schober’s slightly saccharine poetical tribute, performed and recorded since, variously transposed, by many greats of the musical world, amounts to a compliment returned by the art of music to the art of poetry, particularly since Schubert discreetly rearranges (indeed, partially rewrites) Schober’s text to better suit its new format and to make of it the song it so patently aspires to be – a self-reflexive generic yearning common to so many lyrical texts of the romantic era.

Schubert, of course, did not set only individual texts to music. Among his best-known compositions for piano and solo voice are two cycles of songs, “Die schöne Müllerin” (“The Beautiful Miller’s Maid”, 1823) and “Winterreise” (“Winter Journey”, 1828), both settings of poems by Wilhelm Müller. And it is this latter work, to which one of those inaugural Besuch der Lieder events was devoted, that best exemplifies both Schubert’s ability to ennoble poetry while using the potential of verse to scale new musical heights, and the aptitude of a private house concert as the most fitting venue for performances of Lieder.

Wilhelm Müller was not particularly celebrated as a poet during his lifetime, and his reputation has not improved much since. As the writer of the texts turned into songs by Schubert in “Winterreise”, however, he has effectively become the co-author of a grand cultural artefact to be set alongside Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, according to the American baritone Thomas Hampson: an avant-garde prefiguring of such classical modernist tropes as alienation, the fragmentation of the self, and the deployment of allegory to circumvent a repressive regime. From its opening song, jarringly entitled “Gute Nacht” (“Goodnight”), in which a nameless and despairing subject embarks on a solitary journey, to its last, a barely melodic encounter with a street musician that self-reflexively loops back on the cycle to suggest an almost Joycean Moebius strip of narrative (suggests the English tenor Ian Bostridge in a marvellous musico-historical explication of the cycle), “Winterreise” is a dense and multi-layered work of musical literature, or literary music, in which its twin components ennoble each other to create something quite sui generis. Furthermore, Schubert’s music, in which a major chord may on occasion sound more melancholy than a minor, is lent a clarifying dynamic tension by Müller’s spare and naturalistic verse observations of a desolate landscape through the eyes of a desperately lonely wanderer, subjected to the repressions both public and private of a period of reaction and retrenchment.

Such a subtly ironic study of psychological progress underpinned by a range of socio-political aperçus requires an appropriately introspective venue, and there is evidence to suggest that the composer intended it to be produced before smaller, more intimate audiences. A contemporary of his reports on Schubert’s expectations of song performance in general: “I heard him accompany and rehearse his songs more than a hundred times. Above all, he always kept the strictest, most even tempo, except on those rare occasions in which he had expressly indicated a ritardando, morendo, accelerando etc. in writing. Furthermore, he never permitted strenuous expression in a performance. As a rule, the singer merely recounts foreign experiences and impressions, he does not play the person whose feelings he describes; poet, composer and singer must construe the song lyrically, not dramatically.” This precision of understated expression positively militated against the pomp and alienated climate of the concert hall, which demands amplification and exaggeration.

The house concerts staged by Besuch der Lieder at the invitation of private individuals typically feature an hour-long programme of songs – Lieder, chansons, canzoni – assembled by the troupe in consultation with the evening’s host. These “Besuche”, or visits, often take place in a living room or salon before an audience of some 15 or 20 people, usually all friends or relatives of the host; the performers consist of a pianist, playing on the host’s own tuned, non-electric instrument (one of the ensemble’s rare stipulations), one or more singers (rarely, if ever, more than two), and, if desirable, a dramaturge or presenter, who sets the songs in context, historical, musical, and poetical. Although programmes occasionally focus on a particular composer – as for the ensemble’s inaugural two “Schubertiades” – they are more often thematic in nature, assemblies of poems set by various composers united by a common concern: a birthday, a particular city, the passing of the seasons, the pleasures of the garden. When accompanied by the remarks of a dramaturge, such a programme takes on the character of a theme album: a meta-setting of individual songs, as well as, on occasion, entire cycles, that are themselves musical stagings of verse; a mutually complementary symbiosis of text and music in which the two components engage in a dialectic out of which both emerge transfigured.

If the notion of an evening of classical song presented as a theme album is disconcerting, an anachronistic marriage of high romanticism and 1970s Pop, consider the experience of Ian Bostridge, the English star tenor and historian who has authored a book-length study of Schubert’s “Winterreise” and whose performances of that cycle have added to its contemporary renown. When singing the final song in the cycle, “Der Leiermann” (“The Hurdy-Gurdy Man”), he has been inspired, he writes, by “the greatest Dylan love song performance on record, the bitter masterpiece ‘Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right’”, as well as by the figure of Dylan’s tambourine man. The very Dylan whose songwriting was initially as intimate as Schubert’s, until he betrayed the folk-music faithful by “plugging in”; the very Dylan who was honoured by the Nobel Committee, in the year of those two inaugural performances by Besuch der Lieder, for his contribution to the rebirth of music from the spirit of poetry.

www.besuchderlieder.net

* In the interest of full disclosure, the author notes that he himself is a member of Besuch der Lieder, serving as dramaturge. He thanks Christopher Johnson, Edward Rushton and Caroline Wiedmer for useful comments and support.