by Angela Starita

Over the past six years, I’ve intermittently studied weaving. For reasons unknown to me, I’ve wanted to weave for at least the last 20 years, but only as a distant dream. It was part of a larger fantasy, one I wrote an essay about years ago: riding a bike to a clean studio reminiscent of a kindergarten classroom, lots of light, plywood furniture and reams of color in the form of signage and yarn and material. I’d go there every day, work on a project and other women would be working on their projects–parallel experiences but no collaboration. There would be long periods of quiet as we concentrated with occasional meal breaks. By 3 or 4, we might start talking, playing music, showing off our progress. Then we’d clean up our spaces and bike back home. This was how we’d make our living. The specifics of our funding sources remained unresolved —it was a daydream, and I had enough trouble figuring out money flow in real life.

The essay, though, was really about my ambivalence towards fiber art, something I didn’t sense in the younger women who were taking up knitting and crocheting and sewing with what I deemed nary a moment of critical reflection about the historic role of those skills in women’s lives. In articles at the time, needle arts were seen as part of a DIY trend, a resurrection of skills learned from grandmothers and with a fair amount of attendant nostalgia. Both my grandmothers were talented at knitting and sewing, and in fact, I learned the basics of crochet from one of them. The other was in a deep senility by the time I was born, but I learned that she’d been hesitant to teach those skills to her three daughters. Her mantra was go to college and get a good job so you stay in a marriage because you want to, not because you have to.

Though I think her own marriage was a strong one, my grandfather’s insolvency in the middle of the Depression meant she needed to go back to freelance garment work. She’d spend whole nights bent over a crochet beading loom, prepping beads that she’d sew onto evening gowns for a designer she called Miss Ania. Those weren’t skills she wanted her girls to depend on.

Of course, I was mostly wrong about my assessment of the textile art renaissance: women and men were quite conscious of the socioeconomic history behind those skills and were reclaiming them as a way to value the handmade, reject quick consumerism while also trying to explode the gendering of art practices, a correction my workshop fantasy could’ve used. What still goes largely unexamined is the economics of textile art, how to compensate for the making of exquisite objects that also happen to be functional.The questions I didn’t want to answer in my daydream are critical ones.

Last month I studied for three days with two weavers in Perugia, Italy. I learned of their studio from an organization called VAWAA, Vacation with An Artist. I’ve gone on VAWAA trips before, and I suppose I’m the ideal customer: middle-aged dilettante with enough disposable income and vacation time to spend days at a time in another country learning about natural dyes or Umbrian linens. That said, I’m happy to support great work that has few other income streams. And my experiences on those trips have been memorable. Two years ago, for instance, I went to Gee’s Bend, Alabama to study an approach to quilting that is distinctive to the quilters I met there and their ancestors, women who lived on the site of a former plantation on a spit of land delimited by a tributary of the Alabama River. The Gee’s Bend quilts are famous within folk art circles. They’ve even been memorialized on US postage stamps. But for most people, seeing a Gee’s Bend quilt can provoke the kind of jolt you get when you come across an old task done in a wholly new way, a solution that is so clearly right, so simple, that you marvel no one thought of it before. Milton Glazer’s I Heart NY, Le Corbusier’s Maison Do-mi-no. The Gee’s Bend quilts don’t depend on the usual imagery of quilts—stars, log cabins, flying geese—but play with those patterns in weird, unexpected ways. They’re always going outside the framework of the rectangle and letting the shapes and colors take the space they need. In many ways, these quilts are about the ways that colors interact, receding or popping based on combinations. The workshop at Gee’s Bend started with my teachers, Marlene and Loretta, telling me and a friend to look through a garbage bag of fabrics to choose what appealed to us. That would be our starting point, not a pattern or an end use. Marlene would finger a couple of fabrics we’d chosen and ask, “Are these two being good neighbors?”

The painter Lee Krasner learned of the quilters in the mid-60s and arranged to have their work sold at Bloomingdales. When Martin Luther King, Jr. came to Gee’s Bend in 1965, he gave the quilters $200 seed money to form a collective and try to monetize their striking quilts, which manage to be unique to each artist and yet have a visual throughline. Undeniable family resemblance. The collective, called the Freedom Quilting Bee, was launched and the women’s work was featured in a New York Times spread in 1969 with the title “Quilting Co-op Tastes Success, Finds It Sweet.” But in fewer than two years, the Times reported on the venture’s failure despite the popularity of the quilts and their undeniable originality and beauty. To make a living wage from that many hours of labor would require far greater volume or even higher prices. Not a possibility, not even with Bloomingdale’s as a customer.

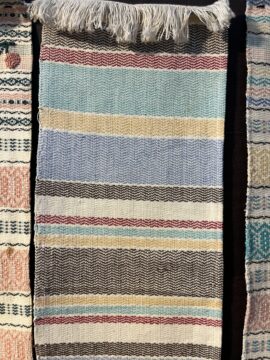

In Perugia, the weaving studio was owned and run by Marta Cucchia, whose great grandmother, Giuditta Brozzetti, had founded the collective in 1921 expressly to record the textile work of women living in the Umbrian countryside. These weavers, most illiterate, were making fabric with patterns passed down from mothers and grandmothers and remembered through rhymes or songs. Flat files in the studio, which is housed in a 13th century church where St. Francis once lived, are filled with samples of their work. Among the dozens of looms in the studio, Cucchia keeps several Jacquard looms, which are programmed through a long set of punch cards and were the predecessors to computers. She used the Jacquard to re-create the pattern of the Perugian linen seen in “The Last Supper,” a two-year-long project that involved studying indistinct parts of the fresco and experimenting with the loom’s punchcards to create an accurate facsimile. Yet Cucchia says she gets no support at all from the city whose patrimony is preserved in these projects. Instead, the workshop is kept alive by grants from foundations outside of Italy. Cucchia hustles to keep the place going, mostly through tours—several groups passed through the studios on the three days I was there—and through lessons for people like me. She makes very little in sales, despite special projects with big-name companies like Fendi. I’d assumed that in Perugia there would be plentiful funds for this kind of heritage work, but the economics of making proved to be as untenable there as in Gee’s Bend.