by Joseph Shieber

When Theodor Adorno composed the aphorisms that formed the first section of Minima Moralia, he was living in exile in Los Angeles in the mid 1940s, a refugee from Nazi Germany. One of the most famous quotes by which Adorno is more widely known, “Wrong life cannot be lived rightly,” is from the 18th aphorism of Part I of the Minima Moralia, in an aphorism entitled “Asylum for the homeless.”

As is typical for many of the aphorisms, “Asylum for the homeless” begins with a pointed cultural criticism before broadening its focus to draw a wide-ranging conclusion about the possibility of a good life in late capitalism.

The pointed cultural criticism with which Adorno begins “Asylum for the homeless,” despite its title, doesn’t literally concern homelessness, but rather with the discomfort attendant with not feeling at home in one’s place of residence. He criticizes “traditional dwellings, in which we grew up,” because “every mark of comfort therein is paid for with the betrayal of cognition; every trace of security, with the stuffy community of interest of the family.” On the other hand, “functionalized [dwellings], constructed as a tabula rasa, are cases made by technical experts for philistines, or factory sites which have strayed into the sphere of consumption, without any relation to the dweller” (translation by Dennis Redmond, here).

This emphasis on the contradictions inherent in attempting to feel at home might seem bizarre, considering the horrors facing those who were literally homeless at the time Adorno was writing: destitute refugees fleeing conflict, or the Japanese Americans forced into internment camps in southern California, not to mention Adorno’s co-religionists at death camps in central Europe. In contrast, during this period, Adorno himself lived in a lovely bungalow, “a quiet nice little house in Brentwood, not far, by the way, from Schönberg’s place,” as he described it in a letter to Virgil Thomson (for quotes from Adorno’s letters to Thomson, I am indebted to a blog post from James Schmidt’s blog, Persistent Enlightenment). Read more »

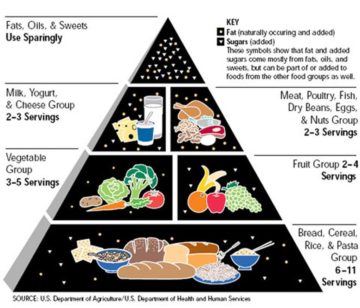

We have many choices when deciding what to eat. For most of human history, however, there has likely been little to no choice at all: people ate what was available to them or what their culture led them to eat. Now things are not so simple. As I mentioned in

We have many choices when deciding what to eat. For most of human history, however, there has likely been little to no choice at all: people ate what was available to them or what their culture led them to eat. Now things are not so simple. As I mentioned in

I enjoyed my days in Delhi School of Economics, but some aspects of the university’s policy in recruitment and promotion of teachers used to trouble me. Let me just give two examples. One is from DSE itself, but illustrative of a much more general problem in university life. We had a middle-aged colleague who had long wanted to be promoted to Readership (Associate Professorship), but failed in the usual process, because he had not done any serious research to speak of in many years. He was full of leftist clichés, and was popular with some sections of leftist students. He first started complaining that he was being passed over in promotion because his ‘right-wing’ colleagues (the term used in Economics those days was ‘neo-classical’—in the same pejorative way the term ‘neo-liberal’ is used nowadays) were biased in undervaluing his work. This after a time did not work, as even some leftist scholars in the Department shared views similar to those of the ‘right-wing’ colleagues on this matter. Then he tried a different tack.

I enjoyed my days in Delhi School of Economics, but some aspects of the university’s policy in recruitment and promotion of teachers used to trouble me. Let me just give two examples. One is from DSE itself, but illustrative of a much more general problem in university life. We had a middle-aged colleague who had long wanted to be promoted to Readership (Associate Professorship), but failed in the usual process, because he had not done any serious research to speak of in many years. He was full of leftist clichés, and was popular with some sections of leftist students. He first started complaining that he was being passed over in promotion because his ‘right-wing’ colleagues (the term used in Economics those days was ‘neo-classical’—in the same pejorative way the term ‘neo-liberal’ is used nowadays) were biased in undervaluing his work. This after a time did not work, as even some leftist scholars in the Department shared views similar to those of the ‘right-wing’ colleagues on this matter. Then he tried a different tack. It’s my oldest memory. I am three, standing harnessed between my parents, in a brand-new two-seater 1959 Jaguar convertible roadster. We are on an empty gravel road someplace in Virginia and my Dad decides to let his new baby fly. I can see In front of me the windshield and, below, a gray leather dashboard that has two things of great interest…a speedometer and a tachometer. The motor hmmmmmms as he takes the car through the forward gears, the tachometer first rising and then falling, the speed increasing. The big whitewall tires are crunching the rough road; cinders are flying; we hit 60 MPH, then 70, then 80; and I’m clapping my hands and piping out “Faster, Daddy! Faster!” My mom goes from worried to furious “Slow down, Ernie, slow down!” As he passes 90, I look down for a moment and she’s slapping her yellow shorts. I peek at the rearview mirror and see a huge cloud of dust. 95, 100, and finally 105. Then without warning, and without using the brakes, he starts to slow, gradually downshifting; the speedometer and tachometer fall; and that’s where my memory ends.

It’s my oldest memory. I am three, standing harnessed between my parents, in a brand-new two-seater 1959 Jaguar convertible roadster. We are on an empty gravel road someplace in Virginia and my Dad decides to let his new baby fly. I can see In front of me the windshield and, below, a gray leather dashboard that has two things of great interest…a speedometer and a tachometer. The motor hmmmmmms as he takes the car through the forward gears, the tachometer first rising and then falling, the speed increasing. The big whitewall tires are crunching the rough road; cinders are flying; we hit 60 MPH, then 70, then 80; and I’m clapping my hands and piping out “Faster, Daddy! Faster!” My mom goes from worried to furious “Slow down, Ernie, slow down!” As he passes 90, I look down for a moment and she’s slapping her yellow shorts. I peek at the rearview mirror and see a huge cloud of dust. 95, 100, and finally 105. Then without warning, and without using the brakes, he starts to slow, gradually downshifting; the speedometer and tachometer fall; and that’s where my memory ends. The peopling of Polynesia was an epic chapter in world exploration. Stirred by adventure and hungry for land, intrepid pioneers sailed for days or weeks beyond their known horizons to discover landscapes and living things never before seen by human eyes. Survival was never easy or assured, yet they managed to find and colonize nearly every spot of land across the entire southern Pacific Ocean. On each island, they forged new societies based on familiar Polynesian models of ranked patrilineages, family bonds and obligations, social care and cohesion, cooperation and duty. Each culture that arose was unique and changeable, as islanders continually adjusted to altered conditions, new information, and shifting political tides. Through trial and hardship, most of these civilizations—even on some of the tiniest islands, like

The peopling of Polynesia was an epic chapter in world exploration. Stirred by adventure and hungry for land, intrepid pioneers sailed for days or weeks beyond their known horizons to discover landscapes and living things never before seen by human eyes. Survival was never easy or assured, yet they managed to find and colonize nearly every spot of land across the entire southern Pacific Ocean. On each island, they forged new societies based on familiar Polynesian models of ranked patrilineages, family bonds and obligations, social care and cohesion, cooperation and duty. Each culture that arose was unique and changeable, as islanders continually adjusted to altered conditions, new information, and shifting political tides. Through trial and hardship, most of these civilizations—even on some of the tiniest islands, like  The United States has always faced a fundamental tension. On one side are those who champion, enforce, and/or profit from hierarchies of power: white supremacist racism, sexist patriarchy, Christian fundamentalism, and capital concentrations chief among them. Arrayed against these hierarchies of power are people who promote and work for racial equality, gender and sexual equality, cultural tolerance, the amelioration of poverty, and genuine freedom both for and from religious beliefs and practices.

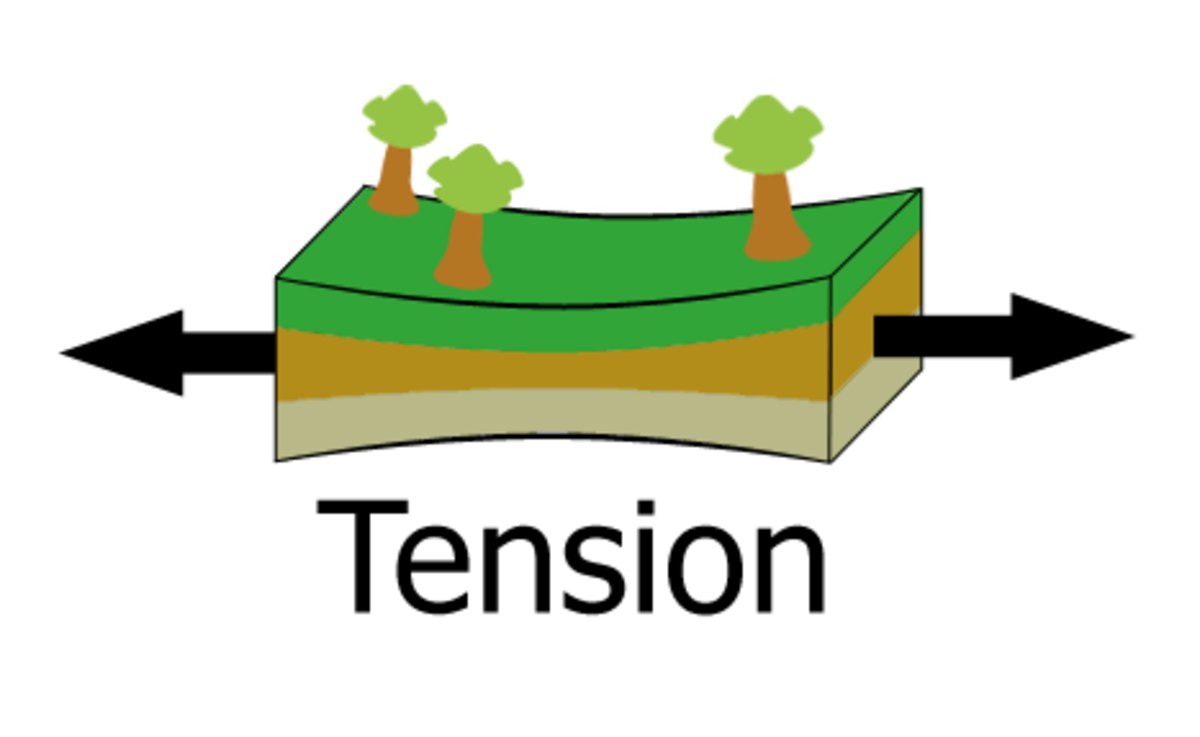

The United States has always faced a fundamental tension. On one side are those who champion, enforce, and/or profit from hierarchies of power: white supremacist racism, sexist patriarchy, Christian fundamentalism, and capital concentrations chief among them. Arrayed against these hierarchies of power are people who promote and work for racial equality, gender and sexual equality, cultural tolerance, the amelioration of poverty, and genuine freedom both for and from religious beliefs and practices.

By a happy chance, the section I was invited to read from, alongside Andreas Flückiger and William Brockman, two associates of the Foundation, at the

By a happy chance, the section I was invited to read from, alongside Andreas Flückiger and William Brockman, two associates of the Foundation, at the