by Rafaël Newman

It’s the final day of February 2022, a month that began with the centenary of the publication, on February 2, 1922, of Ulysses, on what was also the 40th birthday of its author, James Joyce. Commemorations were held, among other places, in Dublin, where Joyce was born and which plays a central role in the novel, and in Zurich, where Joyce wrote parts of Ulysses, where he died, and where he is buried.

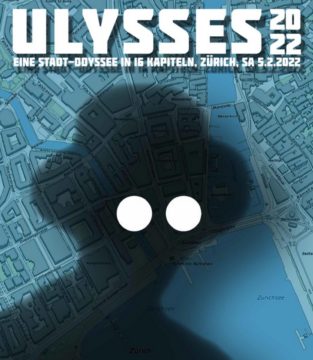

The commemoration in Zurich took the form of an all-day reading of sections of the novel at thematically appropriate locations throughout the city. The marathon was organized by friends of the James Joyce Foundation, a center for the study of the writer’s works under the direction of the eminent Swiss Joyce scholar Fritz Senn; and because I have myself been involved in other events organized by the Foundation, and count among my acquaintances people associated with it, I was asked to take part, on Saturday, February 5, as a reader.

By a happy chance, the section I was invited to read from, alongside Andreas Flückiger and William Brockman, two associates of the Foundation, at the James Joyce Pub in Pelikanstrasse in downtown Zurich, was the Cyclops episode, the 12th of the novel’s 18 chapters. This pleased me because I have cherished the episode for years, in part because my Greek teacher at high school had begun our reading of Homer’s Odyssey with the ninth book of that 24-book poem, in which the Greek hero cunningly escapes death at the hands of the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, and which serves as the template for Joyce’s episode; and in part because, when I first came to read Ulysses, at university in the 1980s, it was the Cyclops chapter that appealed to me most, as it contained what I found the most cogently political encounter in Joyce’s novel—and politics was what interested me most at the time.

By a happy chance, the section I was invited to read from, alongside Andreas Flückiger and William Brockman, two associates of the Foundation, at the James Joyce Pub in Pelikanstrasse in downtown Zurich, was the Cyclops episode, the 12th of the novel’s 18 chapters. This pleased me because I have cherished the episode for years, in part because my Greek teacher at high school had begun our reading of Homer’s Odyssey with the ninth book of that 24-book poem, in which the Greek hero cunningly escapes death at the hands of the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, and which serves as the template for Joyce’s episode; and in part because, when I first came to read Ulysses, at university in the 1980s, it was the Cyclops chapter that appealed to me most, as it contained what I found the most cogently political encounter in Joyce’s novel—and politics was what interested me most at the time.

My interest, as an ambivalent student of literary theory in the 1980s, freshly radicalized by protests against apartheid and a transatlantic Punk “movement” galvanized by Reagan and Thatcher, was indeed politics—though specifically what was not yet (at least in my circle) known as “identity politics”, in my case involving a Jewish identity. Or rather, “half-Jewish”, since, like Leopold Bloom, the novel’s protagonist, I have a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother.

Such matrilineal niceties are of course of little interest to Bloom’s main antagonist in Joyce’s rewriting of the Homeric episode, in which an Irish nationalist and anti-Semite known only as “the citizen” spits on the floor to show his contempt when Bloom nominates Ireland as his “nation” and goes on to identify himself as belonging to the Jewish “race” as well. In the citizen’s Ireland, there is no room for what we now call “diversity”. He and his fellow public-house politicians ridicule Bloom’s stammering attempt at a nuanced, realist construction of nationhood—one that takes account of historical vicissitudes and includes within its purview all those with a quotidian interest in their contingent habitus—and prefer instead a parochial, chauvinist, idealist nationalism, one based, in Ireland’s case, on Gaelic-Catholic, ethno-religious homogeneity. And, when Bloom tries to placate the citizen by stressing their common Judeo-Christian heritage (“Your God was a jew. Christ was a jew like me”), his opponent hurls a biscuit tin at his head, in a gesture calqued on the blinded Polyphemus attempting to murder the vengeful braggart Odysseus.

This juxtaposition, of an archaic, tribalist “Kulturnation” with a modern, voluntarist “Willensnation”—the latter paradoxically championed by a titular member of a supposedly “tribal” ethnicity—appealed to me in the mid-1980s, since it mirrored the progressive politics of my then-nascent aspiration and reflected the “mosaic” view of Canadian multi-ethnicity drafted by Pierre Trudeau in response to the American cliché of the “melting pot”. In the Canadian prime minister’s model, various cultural identities could co-exist under a common, bloodless charter, enhancing and embellishing each other, and their mutual project, without for all that dissolving or disappearing: a “post-nationalism” avant la lettre.

When I re-read the Cyclops episode now, nearly forty years later, at the James Joyce Pub in Zurich, I was struck by something else, something that was difficult to ignore in our performance venue in 2022, and which must have seemed too obvious to be emphasized during my first encounter with the chapter in 1985. For the scene takes place, of course, in a drinking establishment, and there is as much talk among Bloom’s interlocutors of his abstention from alcohol, and of their own thirst for it, as there is of sectarian politics. In the world as imagined by the chapter’s nameless narrator (whose part I had been assigned this past February 5, while Andreas read Bloom and William read the citizen), Joyce’s hero is set apart from his fellow Irishmen as much by his apparent refusal to join in the ritual of buying rounds of Guinness (known jocularly as “wine of the country”), proposing toasts, and relishing inebriation, as he is by his putative ethno-religious otherness. Indeed, the narrator assigns indulgence in alcohol as central to Irish national identity, in 1904, prior to the Irish Republic’s independence from the UK, with the citizen advocating an essentialist view of national character while Bloom implicitly represents the tiresomely moralist position that “Ireland sober is Ireland free”:

So then the citizen begins talking about the Irish language and the corporation meeting and all to that and the shoneens that can’t speak their own language and Joe chipping in because he stuck someone for a quid and Bloom putting in his old goo with his twopenny stump that he cadged off of Joe and talking about the Gaelic league and the antitreating league and drink, the curse of Ireland. Antitreating is about the size of it. Gob, he’d let you pour all manner of drink down his throat till the Lord would call him before you’d ever see the froth of his pint. And one night I went in with a fellow into one of their musical evenings, song and dance about she could get up on a truss of hay she could my Maureen Lay, and there was a fellow with a Ballyhooly blue ribbon badge spiffing out of him in Irish and a lot of colleen bawns going about with temperance beverages and selling medals and oranges and lemonade and a few old dry buns, gob, flahoolagh entertainment, don’t be talking. Ireland sober is Ireland free.

“Ireland sober is Ireland free”: in this construction, Ireland’s psychological enslavement to its self-destructive, substance-abusing habit is analogous to its political serfdom under English rule. And, because the abstemious, ethno-religiously “other” Bloom, although born on Irish soil, is construed as the champion of this alienated modern model of a nation, while the crudely Nietzschean, bibulous citizen stands for a pre-modern, corporatist national identity built on jus sanguinis, abstinence becomes a radically anti-nationalist position, while tribal forms of collective identity are associated with ecstatic, addictive behavior.

I couldn’t see this in 1985, of course, because alcohol is so plainly instrumentalized in the Homeric subtext, still so present in my mind at the time—Odysseus himself gets the Cyclops drunk, after all, simply in order to blind him and make his escape—but also in part given my collegiate social commitments of the period, and my consequent “blindness” to my own possibly pathological attachment to rituals of inebriation. In the intervening years, alcohol has come to play a very different, not to say non-existent part in my life, while my critical view of nationalism has only grown stronger; and this altered vision, in turn, colored my reading of the Joycean encounter between inebriated chauvinism and abstinent post-nationalism on the centenary of Ulysses’ publication, as I recited Joyce’s text in a drinking establishment in Zurich whose interior had been purchased from the Jury’s Hotel bar in Dublin and shipped holus bolus to Switzerland, the magic of its “national” aura presumably intact.

As I have written elsewhere, I view nationalism as a form of addiction. In a piece entitled “Nations Anonymous”, published in 2017 in an edition of the New Zealand journal Ora Nui that featured a dialogue on “national identity” between writers of Maori and European descent, I argued, half in jest, for a 12-steps program for nationalists, on the lines of Alcoholics Anonymous, and with an analogous appellation:

Nations Anonymous, because the disease of nationalism consists as well in the projection of the addict’s own deficient self onto his or her surroundings so as to fashion an expanded self, a prosthetic self, a phantom self to complete the void: an echoing balm to soothe the wound left by the birth of the nation that is each one of us into a world of disconnection, apathy and alienation.

Now, as this Ulysses centenary month ends with the spectacle of military force projected by one state at, and into, another in the name of ethno-nationalist aims—Russians in Ukraine are said to be suffering abuse in ancestral Russian territories, which calls in turn for a Russian response—I recall the lesson of Joyce’s Cyclops episode: that nationalism proceeds from and requires a monocular narrowing of vision; that the irrational nature of its symbology leads it to answer logical argument with violence; and, centrally, that it operates according to the same pattern as that of addiction, which treats the void created by an originary trauma with behaviors and substances that are soothing in the short term, but ultimately lethal.

And although the precise character of the trauma at the origin of this particular episode of violent acting out is in dispute—Tariq Ali, for instance, identifies as Putin’s casus belli the 2014 coup that toppled Yanukovych; Masha Gessen goes farther back, to the NATO airstrikes on Belgrade in the course of the Kosovo War, which she claims Putin is now re-enacting, in a murderous “cosplay” version of Joyce’s rewriting of Homer; while late-night comedians diagnose a case of “covid-induced paranoia” behind the incursion—what seems clear is the addictive nature of the action. It exemplifies the tripartite construction of the addictive personality, as found in 12-steps literature: a physical component marked by compulsion—to act out with behaviors and substances that are harmful to the body (or state); a mental component marked by obsession—the monomaniacal (ideological) inability to focus on anything other than satisfaction of the self-destructive urge; and a spiritual component marked by self-centeredness—the election of one’s own will as the highest ethical authority (l’état c’est moi).

It is tempting to see Putin as Polyphemus, striking out in rage against Zelensky as the wily Odysseus, who has outwitted him and is now fleeing the morbid re-enclosure of post-Soviet alignment; and there is an even greater temptation to see the Russian president as Joyce’s citizen, fixated on a corporatist linguistic heritage and nursing the wounds of colonial aggression, while Zelensky, whose Jewish ancestry has been variously thematized, is Bloom, the capitalist cosmopolitan, keen to join the post-national world of commerce and liberalism. What is at work here, however, in its simplest expression, is the inevitable process of addictive nationalism, whose drug of choice is war. And war, ultimately, is the most intoxicating wine of the country.