by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

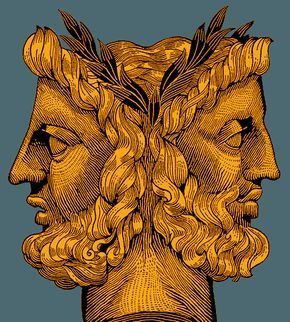

Carrying on an intellectual tradition is a Janus-faced enterprise. Like Janus, the Roman god of transitions, one must look both forward and backward. To start, a tradition must have a causal continuity with its past. The texts and debates from its crucial figures must be carefully preserved and interpreted; distinctive themes must be kept alive, insights appreciated, habits and approaches refined, and founding arguments clarified. Yet living intellectual traditions are not museum pieces. A viable tradition must be applicable to contemporary circumstances. Contemporary practitioners must demonstrate the relevance of their tradition by importing its characteristic principles, practices, and arguments into the fray of current debate. Naturally, this will occasion new challenges and problems for the tradition. Contemporary critics of the tradition will have innovative lines of objection, and material arrangements will change in ways that the founders did not anticipate.

Thus, a tradition’s distinctive insights will need updating and revision. Sometimes, more drastic measures are necessary. Given that any tradition will have internal debates at its founding or in its early development, those who seek to carry on that tradition must be open to the possibility that there are errors in the tradition’s inception – if the tradition’s founders disagreed, at least one was wrong; and maybe all were. The formative moments of a tradition are animated by debates over how the program’s most worthy insights can be developed and perfected. And what can be discarded. Accordingly, those who seek to keep a tradition alive must engage those debates anew, by answering challenges from external critics and by addressing internal disputes among fellow practitioners. Without this forward-looking face, one open to transitions and revisions, the tradition degrades into dead dogma. Read more »