by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Bill Lanouette is the author of “Genius in the Shadows“, the definitive biography of the Hungarian-born American physicist Leo Szilard. Szilard was one of the most creative and far-seeing minds of the 20th century, imagining before anyone else both the reality of nuclear weapons and the seismic political and social changes that would be needed to contain them. As a multidisciplinary thinker without parallel, he contributed deeply to physics, engineering, politics and biology, while having original opinions on virtually every other subject.

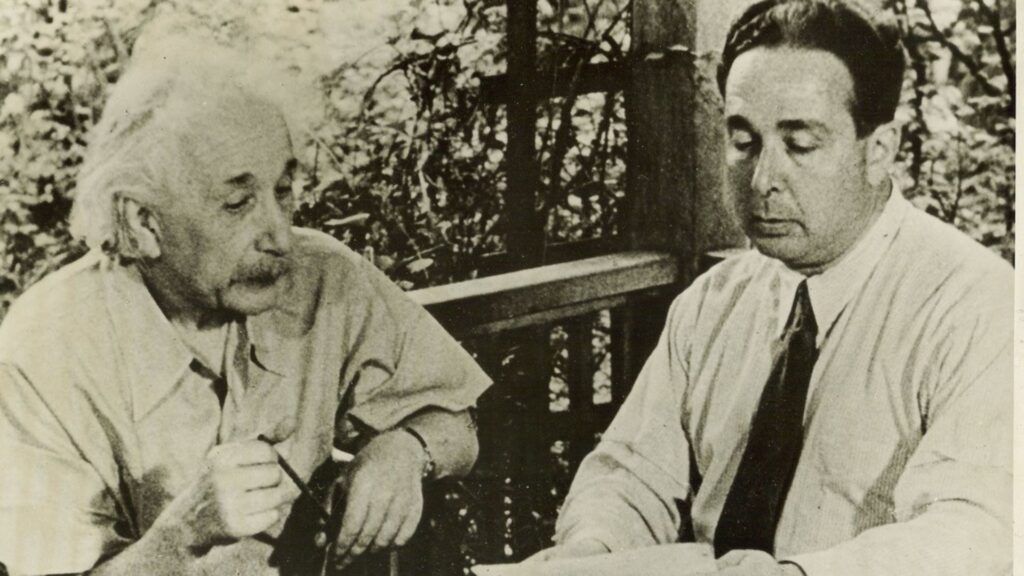

Szilard wrote the famous letter that Einstein sent to President Franklin Roosevelt warning about German’s possible efforts to develop an atomic bomb, started an organization to help Jewish refugee scientist find jobs, tried to argue for international control during his work on the Manhattan Project, went straight to the top to convince leaders like FDR, Truman and Khrushchev to work together to secure the peace and, by acting as an “intellectual bumblebee”, inspired the pioneering work of thinkers as diverse as Claude Shannon, James Watson, Francis Crick and Francois Jacob. If he had lived today, Szilard would have been as much at home in the corridors of power in Washington as in the garage startups of Silicon Valley. He would be what we would call today an “uber-influencer”, in the very best sense of the term.

But, unlike many of his famous contemporaries, Szilard remains the “genius in the shadows”, often ignored in conventional histories and movies about nuclear weapons and the Manhattan Project. Bill and I have a conversation about this remarkable man’s life and legacy and his enduring lessons for our time. For viewers with specific interests, I have broken the video into convenient topical segments which you can view by hovering over them.

1:00 – 12:00: Szilard’s early childhood, education (Hungary had the world’s best schools); fellow Hungarian “Martians” – Teller, von Neumann, Wigner; influence of political upheavals on Hungary’s Jews after World War 1; Szilard’s intense interest in politics (among other things, he came up with a kind of ranked-choice voting system).

17:00 – 28:00: Szilard’s propensity to go straight to the top – he struck up a friendship with Einstein in Berlin; how professors and students both mingled together back then in a multidisciplinary, intellectual free-for-all: “Szilard and Einstein were both lateral thinkers – they would integrate music, philosophy and other fields into their physics conversations.”; the Einstein-Szilard refrigerator and Szilard’s practical bent; Szilard as the father of information theory and influence on Claude Shannon.

28:00 – 41:00: Szilard in England in 1933, his political prescience about the rise of the Nazis and flight from Germany; efforts to set up the Academic Assistance Council to help Jewish refugee scientists that still functions in a different form today; his seminal idea about a nuclear chain reaction while crossing the curb in London in 1933; influence on Szilard of H. G. Wells’s “The World Set Free” that predicted a war fought using atomic bombs.

41:00 – 55:00: Szilard’s peripatetic years – living out of hotels; his propensity for coming up with out-of-the-box ideas, cross-pollinating, influencing other scientists – Francois Jacob called him an “intellectual bumblebee.”; interest in working in India and the Soviet Union; efforts to keep news of fission secret after its discovery by urging other scientists not to publish; Szilard’s pivotal role in convincing Einstein to write a letter to FDR about Germany’s possible quest for atomic weapons.

55:00 – 1:02: Work with Enrico Fermi in doing fission experiments and building the world’s first nuclear reactor, first in New York and then in Chicago; difference between Fermi and Szilard’s temperaments – Fermi was an early riser, Szilard would soak in the bathtub for hours, thinking; the irony of the United States government suspecting that “enemy aliens” like Fermi and Szilard were security risks, when they were trying the hardest to protect the country against Germany.

1:02:00 – 1:14:00: Szilard during the Manhattan Project – his efforts to go straight to the top with his views on the bomb infuriate General Leslie Groves, who tries to have him jailed; Oppenheimer and Szilard – their relationship, difference of opinion between demonstrating the bomb and using it; Szilard’s later efforts to unsuccessfully convince Edward Teller to not testify against Oppenheimer; the irony of Oppenheimer embracing the same views on international control of nuclear weapons that Szilard had been advocating since the war; Szilard’s curious, harmonious relationship with Lewis Strauss; Szilard’s admirable quality of being cordial and friendly with people who could be each other’s nemeses (like Oppenheimer and Strauss).

1:14:00 – 1:29:00: Szilard’s foray into biology, acting as an intellectual bumblebee; the enormous influence and importance of people like him who encourage many others with novel ideas to pursue groundbreaking work, even if they don’t do it themselves; setting up the Pugwash Conferences to connect Soviet and American scientists behind the scene; hitting it off with Khurhschev to whom he promises a supply of Schick razors if the Soviet premier prevents nuclear war; encouraging Khurhschev to set up a hotline with Kennedy.

1:29:00 – 1:41:00: Encouraging Jonas Salk to found the Salk Institute; last years in La Jolla with his wife, Trude Weiss; wishes to have his ashes lofted over the ocean in colorful balloons to “delight the children”; his own secular version of the Ten Commandments; Szilard’s legacy and lasting message for all of us – he “personified the role of the scientist in society” and exemplified thinking outside the box, being fearless and respecting no disciplinary boundaries and always thinking about the social and political consequences of science.