by Ashutosh Jogalekar

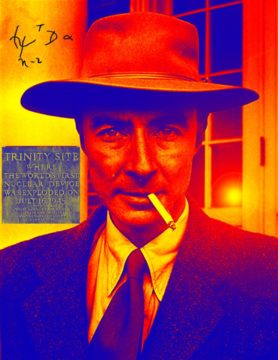

This is the sixth in a series of essays on the life and times of J. Robert Oppenheimer. All the others can be found here.

Colonel Leslie Groves, son of an Army chaplain who held discipline sacrosanct above anything else in life, had finished fourth in his class at West Point and studied engineering at MIT. He had excelled in the course of a long career in building and coordinating large-scale projects, culminating in his building the Pentagon, which was then the largest building under one roof anywhere in the world. In September, 1942, Groves was wrapping up and eager to get an overseas assignment when he was summoned by his superior, Lieutenant General Brehon Somervell. Somervell told Groves that he had been reassigned to an important project. When Groves irritably asked which one, Somervell told him that it was a project that could end the war. Groves had learned enough about the fledgling bomb program through the grapevine that his reaction was very simple – “Oh”.

Robert Oppenheimer is the most famous person associated with the Manhattan Project, but the truth of the matter is that there was one person even more important than him for the success of the project – Leslie Groves. Without Groves the project would likely have been impossible or delayed so much as to be useless. Groves was the ideal man for the job. By the fall of 1942, the basic theory of nuclear fission had been worked out and the key goal was to translate theory into practice. Enrico Fermi’s pioneering experiment under the football stands at the University of Chicago – effectively building the world’s first nuclear reactor – had made it clear that a chain reaction in uranium could be initiated and controlled. The rest would require not just theoretical physics but experimental physics, chemistry, ordnance and engineering. Most importantly, it would need large-scale project and personnel management and coordination between dozens of private and government institutions. To accomplish this needed the talents of a go-getter, a no-nonsense operator who could move insurmountable obstacles and people by the sheer force of his personality, someone who may not be popular but was feared and respected and who got the job done. Groves was that man and more.

Once Groves’s appointment as the head of the secret enterprise was confirmed – an appointment that required, as a condition, the instant promotion to a brigadier general to command the respect of academic scientists who were likely to be Nobel laureates and prima donnas – he moved with breathtaking speed. He sent a subordinate to buy an entire warehouse full of uranium ore and purchased more than 150,000 acres of scrubland in Tennessee to lay down a plant for separating uranium that would employ tens of thousands of people. He started making tours of facilities where the research was taking place, including Chicago where he was dismayed by the uncertain, academic thinking of scientists who he believed thought of him essentially as an overbearing, uneducated idiot; he bristled especially at Leo Szilard’s freewheeling, maverick demeanor and at one point tried to have him incarcerated (Henry Stimson dismissed the silly suggestion). In reality, Groves’s mind was as sharp as anyone’s and his education had been buttressed extensively by coursework at West Point and MIT and in the rough school of real world engineering problems.

It was sometime in October that Groves met Oppenheimer, leading to one of the unlikeliest and most successful partnerships in history. By that time Oppenheimer had become the resident theorist for the project, having been recommended by Lawrence after jettisoning his left-wing activism. The eloquent, 120-pound ivory tower intellectual and the blunt, 250-pound general most improbably hit it off. At least some of the same qualities that dazzled other scientists – the quick mind and all-encompassing knowledge of science must have been prominent ones – impressed Groves as well. Other scientists would look on in wonder, both at Groves’s appointment of the physicist and their successful partnership. But Groves’s biographer, Robert Norris, sees no great mystery in the partnership and succinctly captures the reasons:

“That Oppenheimer and Groves should have worked so well together is really no mystery. Groves saw in Oppenheimer an “overweening ambition” that drove him. He understood that Oppenheimer was frustrated and disappointed; that his contributions to theoretical physics had not brought him the recognition that he believed he deserved. This project could be his route to immortality. Part of Groves’s genius was to entwine other people’s ambitions with his own. Groves and Oppenheimer got on so well because each saw in the other the skills and intelligence necessary to fulfill their common goal, the successful use of the bomb in World War II. The bomb in fact would be the route to immortality for both of them.”

In short, Groves saw that because Oppenheimer who had been left out of the war effort for so long was desperate to contribute, he was pliable. With the benefit of hindsight, Groves later gave a simple reason why he would pick Oppenheimer – “He was a genius…why, he could talk about anything.” One fact that impressed Groves about Oppenheimer was that the physicist immediately sympathized with the security-conscious general’s emphasis on secrecy, something that the other freewheeling scientists that Groves had met didn’t seem to appreciate. But the most important suggestion Oppenheimer made to Groves was that instead of locating the bomb project in a large urban area like Chicago or New York, they should pick a remote, secluded site in which it would be relatively easy to corral cantankerous scientists. After having a few discussions with Oppenheimer and with others who could not suggest a better alternative, it became clear to Groves that he had his man. “It was a real stroke of genius on the part of General Groves, who was not generally regarded as a genius, to have picked Oppenheimer”, said Rabi. The decision astonished everyone; Oppenheimer who had not even led a university department – “who couldn’t have run a hot dog stand”, as one colleague said – was going to be in charge of the greatest scientific and engineering project in history. He would exceed everyone’s expectations.

The first order of business was picking the remote site Oppenheimer had suggested. The answer was clear as day to him – Los Alamos, the place he had discovered as a callow young man and whose mountains called to him every summer. “My two great loves are physics and desert country. It’s a pity they can’t be combined”, Oppenheimer had once said. Now they improbably would be.

At that point the mesa was the location of a boys’ school which was requisitioned quickly by the army under eminent domain. The second order of business was recruiting. The complexity of the problem made it clear that only the best scientists would have the capability of working on it; as it turned out, Los Alamos would turn into the greatest concentration of scientific intellect at one place in modern history, with names like Bethe, Teller, Fermi, Feynman, von Neumann, Bohr and Oppenheimer himself turning into the stuff of physics lore. Oppenheimer’s student and close confidant Robert Serber was already part of the project. He needed others. To do the recruiting he turned on all his powers of persuasion. The problem wasn’t just that scientists would be locating to a remote, ill-equipped site with their families for an unspecified amount of time, it’s that he would have to persuade scientists who were already engaged with other wartime projects – especially radar – to drop what they were doing. This included both Bethe and Rabi who were working on radar at MIT.

To recruit the others, Oppenheimer turned to the high respect that his friend Rabi enjoyed in the community; Rabi used his powers of persuasion to convince people like Bethe. Curiously, Rabi himself did not agree to relocate to Los Alamos, saying that he thought radar was more important to win the war than an untried, untested weapon. Rabi also hit on one of the essential dilemmas of working on weapons of mass destruction when he told Oppenheimer that he did not want the culmination of three centuries of physics to be a weapon that could kill untold numbers. Rabi’s response must have discouraged Oppenheimer, but he respected his old friend enough to ask him to be an occasional consultant to the secret site, which Rabi agreed to. Others like Ernest Lawrence and John von Neumann would also visit as consultants. Rabi also came to Oppenheimer’s help very soon when Groves wanted to put all the scientists into uniform. Confirming his sense that Oppenheimer could be easily manipulated, the physicist at first agreed, only to realize after speaking with Rabi and the other scientists that any such development would make it impossible to recruit scientists and cause rebellion among the existing ones.

Oppenheimer moved to Los Alamos in March 1943, followed by a handful of other physicists like John Manley and Robert Wilson. In “Reminiscences of Los Alamos“, the scientists – especially the ones who had grown up and lived in urban cities of Europe and the Eastern United States – detail their astonishment and wonder as they first encountered the fantastic, austere, primal landscapes of the southwest. Oppenheimer had rightly realized the enticement of the natural surroundings that would bring out the best in his men and women. Los Alamos wasn’t even a town at the beginning; it was a ramshackle collection of what the mathematician Stan Ulam called “huts”. The mud flowed freely after thunderstorms and you carried it everywhere; it was as likely as water to emerge from a tap. Single family housing for the junior scientists was primitive at best, and only the top brass like Oppenheimer and Bethe warranted houses with bathtubs. Edward Teller decided he needed to ship his Steinway piano to the place for creative inspiration, and managed to keep more Nobel laureates awake at night playing Bach and Beethoven on it than he would have been able to anywhere else. Leo Szilard, habitué of hotel lobbies and lover of pastrami who had also been invited to join the project, immediately turned down the invitation, saying that he thought that anybody who would go there would go crazy (given the instant and deep animosity between him and Groves, this was almost certainly for the better).

Along with recruiting from places like MIT, Columbia and Harvard, Oppenheimer also needed to recruit some locals for the administrative staff. Much of this recruiting was done from the lobby of the La Fonda Hotel. One of the most important was Dorothy McKibben, a widow whose husband had died of Hodgkin’s disease back east and who had gone to the sunny southwest to treat her tuberculosis, fallen in love with the place and stayed. The first time she met Oppenheimer at the La Fonda, McKibben was struck by his eloquence and blue eyes and instantly agreed to be the project office manager. For most of the scientists, McKibben’s secret office at 109 East Palace in Santa Fe would be the gateway to the secret mesa. This is where they would be issued passes and sent off along the winding road up the mountains. Feynman, Fermi, Bohr, everyone passed through that office at some point. Many others joined the project, persuaded by Oppenheimer’s passion and his promise of the great consequences of working on it.

Right after Oppenheimer and the other scientists settled into Los Alamos, the first order of business was to bring everyone, especially the younger physicists like Richard Feynman, up to speed on what they had known so far. Robert Serber, a physicist with a steel trap mind, set out to give a set of lectures that would ensure everyone was on the same page. These lectures which were later declassified as “The Los Alamos Primer“, provide a testament to a unique moment in time, an inauguration of a new age when everything was new and there were no real experts. “The goal of this project”, Serber told the attendees, “is to build a practical military weapon in the form of a bomb.” Serber thus made it clear right at the beginning that the project was not basic science but applied science and engineering.

So much has been written about the Manhattan Project’s workings – especially in Richard Rhodes’s groundbreaking “The Making of the Atomic Bomb” – that it would be futile to try to even summarize all of it here. In addition, this particular series focuses on Oppenheimer. But it’s worth summarizing the basic technical challenges to set the scene.

The hardest challenge, as Niels Bohr and others had realized right after fission was discovered, was to separate the minor isotope of uranium, uranium-235, from the more abundant isotope, uranium-238. Since 235 is only 0.7% of naturally occurring uranium and because the chemical properties of isotopes of the same element are virtually identical, this was a herculean task. Many methods were proposed to do this, including Ernest Lawrence’s electromagnetic separation that relied on the tiny difference in mass between 235 and 238 in the presence of an electromagnetic field. Another method, gaseous diffusion, relied on converting the isotopes into gaseous forms and taking advantage of their different diffusion rates through a porous barrier for separation. To accomplish both these goals, vast factories were built in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, factories which at their peak employed almost 50,000 people; at one point, the gaseous diffusion plant at Oak Ridge was the largest contiguous structure in the world.

But what made the project even more promising was the discovery of a new element, plutonium-239, that was even more fissile and that, unlike uranium, would be easier to separate because it was a separate element from uranium rather than just a minor isotope. To create plutonium required a nuclear reactor, and at Hanford in eastern Washington state, a giant industrial and housing complex was constructed that employed about as many people as Oak Ridge. The Manhattan Project was a sovereignty in itself, entire towns springing up in the middle of nowhere that were complete with not just vast labs and factories but with schools, hospitals, libraries, playgrounds, restaurants, barbershops and churches, places where people were born and died, sang and danced and laughed and cried.

The grand conductor who made all that at Los Alamos tick was Robert Oppenheimer. “He was a tremendous intellect.”, Bethe would say later. “I don’t know anyone else who was so quick in comprehending both scientific and human problems.” Oppenheimer now brought all these powers of comprehension to bear on the problem they were collectively trying to solve. He seemed to know everything, not just the chemistry and the physics and the engineering but also the administrative complexities. The same mind that had dazzled his fellow students with the knowledge of French poetry and Dutch at Göttingen now dazzled other scientists and army personnel with his knowledge of different phases of plutonium and the intricacies of machine shop. One of his most remarkable qualities – recognizable to anyone who has worked on a complex scientific or technological project – was to quickly cut through a complex discussion and summarize succinctly what the key questions and solutions might be.

It is enough to provide a sampling of views, many from world-class scientists, to appreciate the capabilities and success Oppenheimer brought to Los Alamos.

Victor Weisskopf, former student of Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr and future director-general of CERN:

“Oppenheimer did not direct from the head office. He was intellectually and even physically present in the laboratory or in the seminar rooms when a new effect was measured, when a new idea was conceived. It was not that he contributed so many ideas or suggestions; he did so sometimes, but his main influence came from his continuous and intense presence, which produced a sense of direct participation in all of us. It created that unique atmosphere of enthusiasm and challenge that pervaded the place throughout its time.”

Bethe:

“Los Alamos might have succeeded without him, but certainly only with much greater strain, less enthusiasm, and less speed. As it was, it was an unforgettable experience for all the members of the laboratory…that this was true of Los Alamos was mainly due to Oppenheimer. He was a leader. It was clear to all of us, whenever he spoke, that he knew everything that was important to know about the technical problems of the laboratory, and he somehow had it well organized in his head. But he was not domineering, he never dictated what should be done. He brought out the best in all of us, like a good host with his guests.”

Lee DuBridge, future president of Caltech:

“He could read a paper – I saw this many times – and you know, it’d be fifteen or twenty typed pages, and he’d say, ‘Well, let’s look this over and we’ll talk about it.’ He would then flip through the pages in about five minutes and then he’d brief everybody on exactly the important points…He had a remarkable ability to absorb things rapidly.”

Robert Wilson, one of the world’s foremost particle accelerator designers who later designed Fermilab, talks about a remarkable quality that Oppenheimer had, which seemed to be to briefly impart his intelligence, his quickness and comprehension to others in his presence; it was as if a superhero had temporarily endowed a mere mortal with his powers:

“In his presence, I became more intelligent, more vocal, more intense, more prescient, more poetic myself. Although normally a slow reader, when he handed me a letter I would glance at it and hand it back prepared to discuss the nuances of it minutely. Out of his presence the bright things that had been said were difficult to reconstruct or remember. No matter, the tone had been established. I would know how to invent what it was that had to be done.”

Oppie, as many still called him, seemed to know everyone who worked at Los Alamos, often on a first name basis, handling Nobel laureates and janitors with equal respect and ease. To those who hadn’t met him before, he seemed to have the uncanny knack of anticipating people’s problems before they had a chance to elaborate on them; he once accosted an irate pregnant woman as she was walking and gave her sage advice on the pregnancy, leaving her astonished.

The one difficulty he had was with Edward Teller. The volatile Hungarian scientist who had been recruited early on the project was known to come up with brilliant ideas and then leave it to others to work out the details. He had great initiative, but he lacked follow through. In contrast, the thoroughgoing and level-headed Hans Bethe could follow through on a problem with the tenacity of a terrier until it got addressed. Not surprisingly, Oppenheimer made Bethe and not Teller the head of the important theoretical physics division at Los Alamos. The slight stung Teller and was to last all his life. And yet even Teller called Oppenheimer the best lab director he had ever seen. Given his sentiments about the physicist later in his life, Teller’s words from 1983 are remarkable:

“Throughout the war years, Oppie knew in detail what was going on in every part of the laboratory. He was incredibly quick and perceptive in analyzing human as well as technical problems. Of the more than ten thousand people who eventually came to work at Los Alamos, Oppie knew several hundred intimately, by which I mean that he knew what made them tick. He knew how to organize, cajole, humor, soothe feelings – how to lead powerfully without seeming to do so. He was an exemplar of dedication, a hero who never lost his humaneness. Disappointing him somehow carried with it a sense of wrongdoing. Los Alamos’s amazing success grew out of the brilliance, enthusiasm and charisma with which Oppenheimer led it.”

Bethe was also thankful to Oppenheimer for negotiating an open culture of discussion at the laboratory. Groves and the army initially wanted strict compartmentalization, with everyone only knowing things on a need-to-know basis. They had fundamentally misunderstood the way science works; through debate and discussion, point and counterpoint. Oppenheimer was critical in working out an arrangement with Groves in which everyone in the technical area could freely discuss what they were working on in symposia, while overall security and information flow would be in the hands of the army.

How seriously the army took security seriously would be something Oppenheimer would not appreciate, and this lack of appreciation would have serious consequences for his life. Oppenheimer’s background check had revealed to the army what they considered deeply alarming political associations, with several family members and friends being members of the communist party. That was one of the sticking points in appointing him director. It is an indication of Groves’s appreciation of his abilities and the urgency of what needed to be done that, in July 1943, Groves overrode his officers’ objections and asked them to clear Oppenheimer, irrespective of whatever information they had about it.

But the officers who were working for Groves, in particular two intelligence officers named Boris Pash and John Lansdale, were like bloodhounds. Two episodes in particular set them off on a hunt with longstanding repercussions for Oppenheimer. In the winter of 1942, before he was about to move to Los Alamos, Oppenheimer invited his close friends Haakon and Barbara Chevalier for dinner at their Eagle Hill apartment in Berkeley. The tall, handsome Chavelier had been teaching French at the university for several years. He adored Oppenheimer. The two shared not just intellectual but also political interests. Both were active in left wing organizations, and Chevalier was a card-carrying member of the communist party.

During dinner Oppenheimer and Chevalier had repaired to the kitchen to fix the drinks, when Chevalier told Oppenheimer that a friend of his who worked for Shell Oil, a communist named George Eltenton, was in touch with someone at the Russian embassy. Eltenton and Chavelier thought that since Russia was an ally of the United States and was bearing the brunt of the assault by Nazi Germany – the titanic Russian counteroffensive at Stalingrad, one in which the Russians would incur more casualties than American casualties during the entire war, had begun that winter – the United States ought to share some information on the bomb project with the Russians. Eltenton had told Chevalier that should Oppenheimer choose to share any information of this kind, he had the means to communicate it to his contact at the embassy. “But that would be treason”, Oppenheimer had immediately said. Chevalier had backed down, and the conversation had quickly ended. The entire conversation had lasted about ten or fifteen minutes, and yet it would transmogrify into a splinter that would lodge into Oppenheimer’s head and cause havoc.

The other incident happened in the summer of 1943. Even after marrying Kitty, Robert had continued to see Jean Tatlock, in part because of genuine empathy for her psychological problems and in part because he was still in love with her. During a visit to Berkeley to wrap up some work, Robert met Jean for dinner and the two spent the night together. They were tailed by intelligence agents who recorded the couple’s activities. Tatlock was a known communist, and Robert’s meeting with her evoked both suspicion and scorn in the security officers’ minds.

In August 1943, Boris Pash invited Oppenheimer for a routine conversation in which he was going to ask Oppenheimer about the activities of one of his students, Rossi Lomanitz. Along with some of Oppenheimer’s other students like David Bohm and Robert Weinberg, Lomanitz had been under suspicion and tailed by army intelligence officers for meeting with known communist members. Unknown to Oppenheimer, Pash had put a microphone in the room and was recording the interview. When Pash started asking Oppenheimer about Lomanitz, to his surprise, Oppenheimer started talking about what had transpired in his kitchen six months earlier. But then he made up a completely fabricated story. Without divulging names, he told Pash that he had been approached about transmitting information to the Soviets, but not by one person but by three. The use of the plural made all the difference. It made Pash and his fellow officers suspect a whole ring of conspirators. When Pash pressed Oppenheimer on the names, Robert wouldn’t divulge them, saying that because no information had been transmitted and because he considered the person who was asking a close friend, he would not be comfortable naming them.

As Oppenheimer’s biographers say in their book, Oppenheimer had swallowed a time bomb, one which would explode a decade later, with ruinous consequences for him. He badly underestimated the alarms that must have gone off in Pash and the others’ heads and the tenacity with which they would try to pursue the people who he had indicated had approached him. And to be fair to them, they were doing their job. It was Oppenheimer who, by fabricating what he later called a “cock and bull story”, had made them latch on to him like a terrier. Pash had flatly recommended to Groves that Oppenheimer should not be hired for the project; Lansdale, on the other hand, after interrogating him and later also interrogating Kitty who went to some lengths to tell Lansdale how important she considered her husband and his job, had concluded that Oppenheimer was a loyal American whose ambitions for himself were evidence that he would not divulge any sensitive information. Groves cleared Oppenheimer even after knowing about his conversation with Pash, but the ‘Chevalier affair’, as it came to be known, eventually came to destroy Robert Oppenheimer’s life and career.

As the project progressed, the strain on Oppenheimer started showing. The compulsive smoking did not abate, and he shrank to little more than a hundred pounds. But the frail physique only enhanced the perception of his intellect and leadership; it was as if the largeness of his mind made up for the smallness of his body. At least once he thought the strain was too much and discussed quitting his position with Robert Bacher, a talented experimental physicist who was associate director, but Bacher convinced him to stay on because there was no one else who could get the job done.

In September 1943, Niels Bohr found out that his life was in danger; the Nazis who until then had treated the Danes much better than the doomed Poles and other Eastern Europeans, in part because they wanted to exploit Denmark’s natural resources, lost patience; Bohr was under imminent threat of arrest and possible execution. He was spirited away to Sweden by boat and then to Britain and Los Alamos by air. He came to Los Alamos with a radical mission. In the realm of atomic physics, Bohr had recognized that seemingly opposite qualities of subatomic entities – like waves and particles – were both crucial for understanding reality; it was just that both could not be observed at the same time in the same experiment. He called this paradoxical idea complementarity. Now Bohr had a millennial vision about the complementarity of nuclear weapons: he saw that the same bombs which would threaten to destroy cities and civilizations could also bring about world peace because of their very danger. When he arrived in Los Alamos, one of his first questions was, “Is it big enough?” What he meant to ask was whether the bomb was big enough, scary enough, to compel nations to come together and do everything they could to avoid nuclear war. Bohr’s thinking had a very striking influence on Oppenheimer’s thinking; you see it as a subtle, often unseen but present, thread of Ariadne running through the physicist’s writing and postwar activities. Later Bohr had a disastrous meeting with Churchill in which Churchill failed to see that the bomb wasn’t just another big weapon. His meeting with FDR would also not lead to substantial, actionable conclusions. But the seed had been planted, most notably in Oppenheimer’s mind.

A particular challenge that arose in the fall of 1944 was the discovery by Emilio Segre, a protege of Enrico Fermi’s, that the “gun method” in which two halves of fissile material were violently shot at each other to form a critical mass would not work for plutonium. Segre had found that plutonium bred in the nuclear reactors at Hanford contained plutonium-240, an isotope of plutonium that would generate so many neutrons from spontaneous background emission that using the standard method of bomb assembly would cause a premature detonation, a fizzle. Oppenheimer had to reorganize the entire laboratory at this critical juncture to explore a completely new method for the plutonium bomb – implosion, in which a sphere of plutonium would be compressed suddenly inwards using high explosives. He brought in outside experts like George Kistiakowsky and John von Neumann to handle the fearsome complexity involved in the perfectly symmetrical compression of this sphere which was necessary for a successful implosion.

The implosion method was so untested and novel that it was decided to test the bomb before actual use; the gun method for the uranium bomb was considered reliable enough to not need a test. After the winter of 1944 and Germany’s last desperate counteroffensive – the Battle of the Bulge – it became clear through allied intelligence and the so-called Alsos mission that the Germans were not even close to building a bomb. But Japan was still fighting on, and suicidal, gruesome battles like Iwo Jima and Okinawa had made it clear that the Japanese would rather undergo mass national suicide than surrender. The feeble peace feelers from a small peace faction inside the Japanese government had been too muddled for the Allies to not consider demanding unconditional surrender (the question of whether the Japanese were going to surrender and whether the Allies should have made more efforts to investigate any such efforts is a very complex one: two references which do a good job exploring these topics are Tsuyoshi Hasegawa’s “Racing the Enemy” and Evan Thomas’s recent “Road to Surrender“. The two main questions to ask are what the Japanese were actually doing and what the Allies thought and knew they were doing).

At the end of May, 1945, Secretary of State Henry Stimson appointed a committee called the Interim Committee to advise the government on the use of the bomb. Fermi, Lawrence, Compton and Oppenheimer were appointed as scientific advisors to the committee. This was a very high profile group – other members included General George Marshall – Chief of Staff, Groves, James Conant, Vannevar Bush and James Byrnes, a close confidant of FDR and the new president Harry Truman’s representative. On May 31st the committee met and discussed the possibility of a demonstration of the bomb before using it. After the war Lawrence was often cast as the conservative supporter of nuclear weapons and Oppenheimer the liberal opponent. Both views were caricatures, but curiously, during the Interim Committee meeting Lawrence supported a demonstration and Oppenheimer opposed it. Oppenheimer’s reasons were not entirely unreasonable: What if the bomb were a dud? What if the demonstration failed to have a psychological impact? What if the Japanese brought American POW’s into the area? Marshall and Stimson were sympathetic to the idea of a demonstration, but James Byrnes who was a hawk and who had Truman’s ear prevailed over them. Ultimately, Oppenheimer’s powers of persuasion convinced the committee that actual use might be the best option. The bomb was to be used on a military target, preferably a production plant with workers’ houses surrounding it (Hiroshima and Nagasaki did not fit this description).

The test of the implosion bomb was scheduled to be held in July, 1945, in a stark, barren patch of desert called the Jornada del Muerto – the journey of death – near Alamogordo, about 300 miles south of Los Alamos. To Groves Oppenheimer had recommended what he thought would be an appropriate codeword for the test – Trinity. The name came to him from a holy sonnet by John Donne’s poem, “Batter my heart, three-person’d God”. Jean Tatlock had introduced Oppenheimer to Donne, and his poetry must have seemed metaphysical and millennial enough for him to provide the name for a weapon that could destroy the world. It could also have been a subtle tribute; Tatlock had committed suicide in January 1944, unable to battle the demons inside her mind anymore.

A smaller version of Los Alamos went up in a few days at the site, with a 100-foot tower hosting the bomb. The weather had been temperamental and the date and time had had to be postponed several times. The scientists and army officials had been waiting with bated breath the night before for a torrential rainstorm to clear up. The plutonium core of the bomb had been delicately assembled and shipped to the site in a sedan in which it was babysat by Philip Morrison. Groves and others were trying to get the chain-smoking Oppenheimer, who was in a state of high-strung tension, to calm down and get some sleep. The whole night which had been surreal enough because of what it was leading to was made even more surreal by various sundry events; Enrico Fermi taking bets on whether the bomb would destroy the state of New Mexico; a radio station broadcasting Tchaikovsky suddenly hijacking radio traffic on the site; a whole chorus of mating frogs causing a terrific noise after the thunderstorm.

Finally a window of clear weather opened up and the test was scheduled for 5:30 AM. All the tension, all the brilliance, all the misgivings and triumphs, had built up to this moment. As the countdown dwindled to zero, Edward Teller passed suntan lotion to everyone and Richard Feynman climbed into a truck without wearing sunglasses based on the theory that since glass blocks UV radiation, he might only be temporarily blinded. “Dr. Oppenheimer, on whom had rested a heavy burden, grew tenser as the last seconds ticked off.” noted an army official standing next to Oppenheimer. “He scarcely breathed. He held on to a post to steady himself. For the last few seconds, he stared directly ahead.” At 5:29:45 AM the firing circuit closed, 32 detonators placed around the high explosive surrounding the plutonium core in a precise geometric arrangement went off, the explosive set off shock waves that compressed the core to supercritical densities, and in a blinding flash, the neutrons from a beryllium-polonium initiator at the center caused plutonium atoms to fission with unimaginable force and speed. For a brief moment the conditions resembled ones shortly after the Big Bang.

As the menacing mushroom cloud rose high into the atmosphere, the light and delayed shock wave rumbled and bored into the men’s hearts. As Rabi said, “A new thing had been born; a new control; a new understanding of man, which man had acquired over nature.” Oppenheimer, emotion writ large on his face, remembered the famous line from the Bhagavad Gita; “Now I am become death, destroyer of worlds.” They had done it. He had done it. But amidst the superlative, vivid, competing enunciations of articulate men struggling to describe an overwhelming force that threatened to pull the temple over humanity’s head, a cruder, yet much more perceptive remark shorn of baroque description by physicist Kenneth Bainbridge, director of the test, struck Oppenheimer as the best thing anyone ever said about Trinity: “Now we are all sons of bitches.” Less than a month later, two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki killed a hundred and twenty thousand people in seconds. Hans Bethe’s reaction provides the coda: “At first we said to ourselves, ‘We have done it.’ And then we asked ourselves, ‘What have we done?’

Sources:

- Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer”, 2005

- Richard Rhodes, “The Making of the Atomic Bomb”, 2005

- Abraham Pais, “J. Robert Oppenheimer: A Life”, 2006

- Lawrence Badash, Reminiscences of Los Alamos, 1980

- Charles Thorpe, “Oppenheimer: The Tragic Intellect”, 2006

- Post: Lessons on management styles from Robert Oppenheimer, Hans Bethe and Edward Teller, 2016