by Jochen Szangolies

Turn your head to the left, and make a conscious inventory of what you’re seeing. In my case, I see a radiator upon which a tin can painted with an image of Santa Claus is perched; above that, a window, whose white frame delimits a slate gray sky and the very topmost potion of the roof of the neighboring building, brownish tiles punctuated by gray smokestacks and sheet-metal covered dormers lined by rain gutters.

Now turn your head to the right: the printer sitting on the smaller projection of my ‘L’-shaped, black desk; behind it, a brass floor lamp with an off-white lampshade; a black rocking chair; and then, black and white bookshelves in need of tidying up.

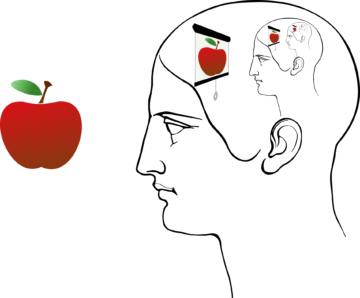

If you followed along so far, the above did two things: first, it made you execute certain movements; second, it gave you an impression of the room where I’m writing this. You probably find nothing extraordinary in this—yet, it raises a profound question: how can words, mere marks on paper (or ordered dots of light on a screen), have the power to make you do things (like turning your head), or transport ideas (like how the sky outside my window looks as I’m writing this)? Read more »